As revenue declines from one 'sin tax,' California considers tapping another for children's programs

The story was produced as a project for USC Annenberg's 2018 National Fellowship. It also ran in LocalNewsMatters.org.

Other stories in this series include:

How filmmaker Rob Reiner put early childhood in the limelight

What did California's novel approach to funding early-childhood programs achieve?

Early childhood advocates see cannabis challenges rise as tobacco sales fall

One California county epitomizes positive impact of home visiting amid national trend

More California school administrators gain skills as early-childhood leaders

How do you tell the story of a huge early childhood program over time?

Taxes on recreational marijuana "won't be a panacea," one First 5 official said, but advocates still hope they'll be directed toward early intervention and education.

This article is part of a series about First 5 — a tobacco tax initiative in California passed by voters 20 years ago to fund services for young children, from birth to kindergarten age. The series is supported by a University of Southern California 2018 Center for Health Journalism fellowship.

Forming relationships with nontraditional partners, such as businesses, getting more involved in state and local policy, and even restructuring a mortgage are a few of the ways that leaders of California’s 58 First 5 commissions say they are coping with declining revenue from a statewide tobacco tax while trying to maintain services to families with young children.

The 50-cent tax on tobacco products at one point brought in roughly $550 million annually, according to Camille Maben, First 5 California's executive director. Twenty percent is distributed to a statewide Children and Families Commission and the rest goes to the 58 counties. But now that California has the second-lowest rate of adult cigarette use in the nation, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, annual revenues from the tax have declined to about $273 million, Maben said.

“As a leader in passing some of the most restrictive tobacco policies in the nation, I’m proud to see smoking rates diminish,” Ken Yeager, chair of the First 5 Santa Clara County commission and a member of the Santa Clara County Board of Supervisors, said in an email. “However, this has led to declining funds for First 5 as the organization is almost exclusively funded by the Prop 10 tobacco tax. We must obtain new sources of revenue to continue to have strong impact.”

In addition, early-childhood programs in California experienced over $1 billion in budget cuts during the recession and funding has not returned to pre-recession levels, according to a report from the Learning Policy Institute. That put even more strain on the county-level commissions, Stanford University professor Deborah Stipek, who focused on early childhood as part of a recent report on California's education system, suggested in an interview.

"I don't think First 5 was in a position to make up for huge reductions in resources," Stipek said.

'A built-in problem'

Education Dive: K-12 sent a brief survey to the executive directors of the state’s 58 county First 5 commissions. Thirty-one of them responded, with most saying they are taking a variety of steps to adjust to declining resources, including cutting back on some programs, applying for more grants and dipping into reserve funds.

“We have, from the beginning, required our grantees to explore other options for funding,” Nina Machado, executive director of First 5 Amador, located in the Sierra Nevada region of the state, said in an interview. For over 10 years, the agency has also received additional funding from the state for administering the county’s child abuse prevention council.

Maben notes that in contracts with organizations providing services to families, county commissions have always been required to maintain a financial "cushion to make sure they don’t have to defund a contract midstream."

But some executive directors responding to the Education Dive survey still expressed concern about how the declining funds affect families that are already struggling.

“Building [a] program on a declining revenue stream was always a built-in problem for First 5,” one director wrote in the survey response. “We are most concerned with support for young families returning to a fragmented array and losing the linkages that we've been able to build.”

Others noted that instead of being able to expand programs, they are reducing services.

“None of our programs are yet on a countywide scale, rather we have had to narrow services repeatedly to specific neighborhoods and the highest risk children/parents,” Julie Gallelo, the executive director of First 5 Sacramento, wrote in her response.

And another director said agency staff members are doing more to “serve as subject matter experts” and providing leadership to other local agencies serving children and families. “We learn from our peers, we utilize technology and we capitalize on innovation to continue to see progress experienced over the past 20 years,” the director wrote.

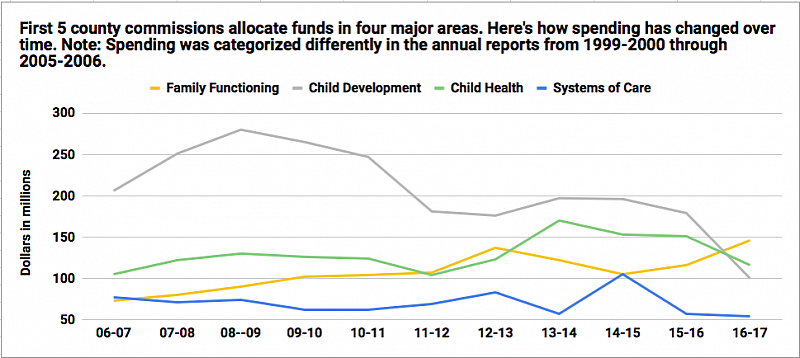

The noticeable decline in spending for child development programs over time is a reflection of the county commissions' inability to sustain programs, their interest in supporting young children's health needs and programs to help families be more resilient, and the availability of other state- and local-funded early-childhood education programs, according to Erin Gabel, deputy director of external and governmental affairs for First 5 California. (Graphic: First 5 California)

Preparing for ‘a real debate’

Meanwhile, many First 5 leaders and early-childhood education advocates are looking to taxes on the state’s new recreational marijuana industry as a potential source of public funding for the developmental screening, home visiting, preschool and other programs that First 5s fund.

“Voters overwhelmingly want to see marijuana money go to early-childhood programs,” Avo Makdessian, the vice president and director of the Silicon Valley Community Foundation’s Center for Early Learning, said in an interview. Makdessian previously served as policy director for First 5 Santa Clara.

In 2016, California voters approved Proposition 64, the Control, Regulate and Tax Adult Use of Marijuana Act, and the state began collecting excise taxes on legal marijuana sales in January of this year. But in May, the state’s Legislative Analyst’s Office released figures showing that revenues were far below initial projections — about $34 million in the first quarter. Additional taxes were collected on cultivation and sales, bringing the first quarter total to about $60 million.

After the second quarter, the state collected another $74 million, but that is still well below the original six-month estimate of $175 million included in Gov. Jerry’s Brown’s budget.

While policy and regulatory issues are not yet settled — and many local governments still don’t allow marijuana businesses or sales — some lawmakers also say the taxes are so high that customers will just continue to do business on the black market.

Other states that use a portion of cannabis tax revenue for education and children's programs include Nevada, Oregon and Colorado, which allocates funds into a competitive grant program for school repair and construction. A separate account provides grants for health professionals, and intervention and prevention programs.

In California, the law directs 60% of the revenues to be deposited into a Youth Education, Prevention, Early Intervention and Treatment Account, and requires the Department of Health Care Services to form an interagency agreement with the Department of Public Health and the Department of Education to implement a long list of education, prevention and intervention programs for children, youth and their families.

But Erin Gabel, the deputy director of external and governmental affairs for First 5 California, said that, realistically, the marijuana tax revenue “won’t be a panacea for anything,” and that education and prevention interest groups have already “lined up” for access to those funds.

“All of that is going to be a real debate,” she said.

Earlier this year, the Silicon Valley Community Foundation commissioned a survey of likely voters, asking for their thoughts on issues facing the state and what the future governor should prioritize. Of all the options for financing publicly funded early-childhood programs presented, including taxing firearm purchases and taxing soda and other sugar-sweetened beverages, dedicating a portion of the existing state taxes on marijuana to programs for children aged five and under was the most popular, according to results shared by email. Seventy-four percent of 800 likely California voters chose that option, and 66.1% support increasing state taxes on marijuana for programs for young children.

“If the revenues bump up,” Makdessian said, “elected officials will know where the electorate will want to spend that money.”

Early-childhood advocates might also have a like-minded governor after next month’s election. Joey Freeman, spokesman for Democrat Gavin Newsom, said the candidate "will champion dual-generation approaches through Prop 64 funding at the state and local levels, like family-nurse coaching, home visiting, and early-childhood education, as well as research-proven strategies to support older youth through community schools and after-school programs.

Education Dive: K-12 asked executive directors of county First 5 commissions about their goals should funding levels increase. Here’s what a few of them had to say:

- “We'd really like to serve more families with home-visiting programs; have a robust screening and referral program for developmental differences; and expand out work increasing the skills of child care providers/helping raise the quality of early-childhood education settings.”

- “Proposition 10 revenue provided a startup investment, but the collaborative work in our community continues to highlight the need for quality services even more. [First 5 Monterey County] would use additional funds to enhance or expand activities associated within four of its five core roles: champion early childhood, make connections, build capacity, fund the work and evaluate impact.”

- "We would like to eliminate the wait list for children who are eligible for subsidized child care, and we’d like to ensure that all children in the county are screened for developmental and social/emotional issues. We’ve made very real inroads in each of these areas, but Prop 10 dollars alone can’t solve the problem. We’ve never had enough money to serve all kids/parents in need."

- “First 5 should be the first partner with the state for children and families. Additional funding and collaboration in this area definitely makes sense for successfully moving forward. Our work is not done. Our ultimate dream is that someday First 5 would no longer be needed [but] our reality tells us that may never be the case.”

With the experience that First 5s already have communicating with pregnant women and parents about the risks of tobacco use, Kimberly Goll, the executive director of the Children and Families Commission of Orange County, said “it’s in the state’s best interest” to use the First 5 infrastructure to educate families about marijuana use during pregnancy or breastfeeding.

“There is so much opportunity there to make sure the messaging is getting to the right population,” Goll said in an interview. “The field of people grabbing for marijuana money is complicated, but we have this unique space. Let’s not shy away because it is a crowded field.”

Working toward well-funded, sustainable systems

When asked in the Education Dive survey where they want their local commissions to direct any increases in funding, the First 5 executive directors who responded largely said they want to continue to see work across multiple areas of children’s development and well-being — health, preventing maltreatment, school readiness, parent coaching and education, and supporting the early-education workforce.

“Significant outcomes cannot be achieved in a piece-meal, segmented manner,” wrote Karen Scott, First 5 San Bernardino’s executive director, “especially with declining Prop 10 revenue.”

[This story was originally published by Education Dive.]