Targeted Part Three: Pasco Sheriff Chris Nocco Has A Controversial Approach - And Powerful Friends Who Don't Question It

This story is part of a larger series by Neil Bedi and Kathleen McGrory, with support from the Fund for Journalism on Child Well-Being, a program of the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2020 National Fellowship.

Other stories in this series include:

Public interest groups take aim at Pasco sheriff’s data-driven policing programs

Pasco PTA: Use of school data to flag potential criminals ‘unacceptable’

Congressman urges probe of Pasco school data program

Bill aims to curb Florida’s data-driven policing programs

Pasco sheriff’s campaign paid $15,000 to top Sheriff’s Office staffer

Foundation cuts off Pasco schools, citing data sharing

Florida lawmakers take steps to limit school-data sharing

Lawsuit: Pasco intelligence program violated citizens’ rights

DeSantis should consider removing Pasco sheriff, GOP congressman says

President Donald Trump and Sheriff Chris Nocco

Tampa Bay Times

Pasco Sheriff Chris Nocco was once asked under oath how he had landed two high-level posts in state government.

“It was the connections that I had made,” he said bluntly.

“I mean, you didn't have to like go and interview along with a hundred other people to get the job or anything?” an attorney pressed.

“No, ma’am,” he said.

Later that month, he told a reporter: “I’m very blessed to have friends that are in high offices.”

Today, Nocco himself is in a high place. A force in local GOP politics, he has twice been elected sheriff without opposition — something that hadn’t happened in Pasco County since World War II. His wife is one of the state’s most prominent Republican fundraisers. Their ties have reached the highest levels of government, including President Donald Trump’s administration.

Since becoming sheriff a decade ago, Nocco has used his connections and clout to grow the department and expand its reach.

He’s also taken the agency in directions that have appalled experienced cops and nationally recognized law enforcement experts.

A Tampa Bay Times investigation in September found that Nocco’s signature initiative — a sprawling intelligence program — uses an algorithm to identify people who might break the law, based on their criminal histories and social networks. The agency sends deputies to their homes, even if there is no evidence of a crime. Former deputies told the Times they had been ordered to make targets’ lives miserable.

Deputies interact with people targeted by the Pasco sheriff’s intelligence-led policing program. Pasco Sheriff’s Office

The Times later revealed that the Sheriff’s Office starts trying to predict future criminals even earlier in life. It keeps a list of schoolchildren who might “fall into a life of crime” that’s built with data such as grades and child welfare records, agency documents show.

The department says the list currently includes more than 400 kids and is only used by school resource officers to provide support and “mentorship.” The kids and their parents are not made aware of the designation.

National experts who reviewed the programs for the Times called them “morally repugnant” and “everything that’s wrong about policing.” Some civil liberties groups — including the ACLU of Florida, Southern Poverty Law Center and Institute for Justice — are considering lawsuits and public advocacy campaigns. Tens of thousands of people have signed a petition demanding the school district stop sharing sensitive student data with the Sheriff’s Office.

Yet leaders in the Republican county and statehouse have been reluctant to weigh in. More than a dozen elected officials did not return phone calls or declined to be interviewed for this report.

Chris Nocco speaks at a 2011 press conference after then Gov. Rick Scott appointed him sheriff of Pasco County. Times (2011)

Nocco became Pasco’s sheriff at 35, with eight years of law-enforcement experience. He set out to remake the agency: building an intelligence arm, hiring retired military officers and giving deputies a new and confrontational rallying cry, “We fight as one.”

The Sheriff’s Office takes pride in those efforts and touts its reliance on data, early adoption of body cameras, and recent work to address mental health and create a cutting-edge research institute as proof of its forward-thinking attitude.

But it has also faced criticism that its deputies have become too aggressive and its leadership too reliant on misapplied intelligence tactics.

Internally, the department has broken into open conflict. Some deputies have resisted the changes and been pushed out amid what they call retaliation. The schism has led to multiple lawsuits, including one that described agency leaders as “intoxicated with power” and willing to “physically abuse, intimidate, incarcerate, extort, and defame in order to ensure their absolute control.”

The Sheriff’s Office has denied the claims.

Nocco (pronounced knock-oh) declined to be interviewed for this story or any others related to the Times’ reporting on his intelligence programs. Instead, the Sheriff’s Office provided a copy of his biography and a 53-page report on how the agency has innovated during his tenure. Nine pages are devoted to intelligence programs. Seven highlight the agency’s partnership with the schools and its programs for kids.

“I am extremely proud of the bond we have created at the Pasco Sheriff's Office with our community over the last 10 years,” Nocco said in a statement. “This bond has allowed us to best serve our community, reducing crime as our population has grown rapidly and focusing on serving the needs of our community.”

In previous memos to the Times, the Sheriff’s Office has said it won’t back down from its intelligence strategies. It accused the news organization of “yellow journalism” and bias against law enforcement.

Even though sheriffs nationwide operate with vast autonomy and little oversight, Nocco stands out as particularly powerful.

His supporters say he’s a born leader whose humble attitude and natural charisma have made him popular among rank-and-file deputies and Pasco residents alike.

“People like him,” said longtime friend Mike Fasano, now the county tax collector. “It’s because of the way he comes across as a likeable person who cares about our community and keeping our community safe.”

Then, there are his connections.

He served as a top aide to Marco Rubio, now Florida’s senior U.S. senator.

His wife, Bridget, helped spearhead fundraising for Rick Scott, the state’s former governor and now its junior U.S. senator.

She’s been the finance director for one of the most important lobbying and public relations firms in the country. Her boss, Brian Ballard, has a long-standing relationship with the president. In 2018, Politico called Ballard the most powerful lobbyist in Trump’s Washington.

That proximity to the upper rungs of the Republican Party has made Nocco untouchable, said Bill Dumas, president of a local organization called Citizens Against Discrimination and Social Injustice.

“He does whatever he wants and there’s no arguing with him — or even sitting down and reasoning with him,” Dumas said.

A POLITICAL STAR

Sheriff Chris Nocco, his wife Bridget Nocco and their daughter attend the sheriff’s swearing-in ceremony in 2011 at Redeemer Community Church in New Port Richey. Times (2011)

In reliably Republican, pro-cop Pasco County, people know Chris Nocco.

He’s the plain-spoken, tough-on-crime lawman with a Philly accent. The former college football player and father of three who tweets Bible verses and motivational quotes.

He wears a patrolman’s uniform, not a suit and tie like some of his predecessors, and he drives the same type of car as his deputies, Fasano said.

Politicians running for office vie for his endorsement. He typically gets what he wants from the County Commission without a fight.

Nocco, 44, wasn’t always on the fast track. After earning his master’s in public administration from the University of Delaware, he spent the first few years of his career hopscotching from one police agency to another.

His first job, as a Delaware State Police trainee, lasted eight months. He resigned because a lieutenant made “derogatory” remarks about his family and faith, he said during a 2011 deposition.

His next stint, with the Philadelphia Public Schools Police, lasted six months.

He went to the Fairfax County Police Department in northern Virginia and stayed almost 3.5 years. Then he moved to Florida, following Bridget back to her home state, where she had a job opportunity.

He quit his next job, as a patrol deputy with the Broward Sheriff’s Office, after ten months. He said during the deposition that he didn’t want to work for Sheriff Ken Jenne, a powerful Democrat who would later plead guilty to fraud and tax evasion charges.

Nocco said he believed Jenne’s refusal to pay overtime for units like the SWAT team had put lives in danger. “Even as a patrol officer or deputy on the road, you knew he was just not a good sheriff to work for,” he said.

From there, Bridget helped him segue into politics. Just two months before the 2004 election, he became field director for Republican President George W. Bush’s campaign in Broward County. (The liberal county went overwhelmingly for Bush’s Democratic challenger, John Kerry.)

Nocco spent the next four years as an aide in the Florida House of Representatives, working his way up to deputy chief of staff for Rubio, who was then House speaker.

He forged close ties with many members of Pasco’s political class. That included Fasano, then an influential state senator; Rep. Will Weatherford, who would later ascend to House speaker; and Pasco Sheriff Bob White, who travelled to Tallahassee with the Florida Sheriffs Association.

Nocco’s immediate supervisor, Richard Corcoran, was also from Pasco and would later be elected to the House and serve as speaker. Corcoran is now state education commissioner.

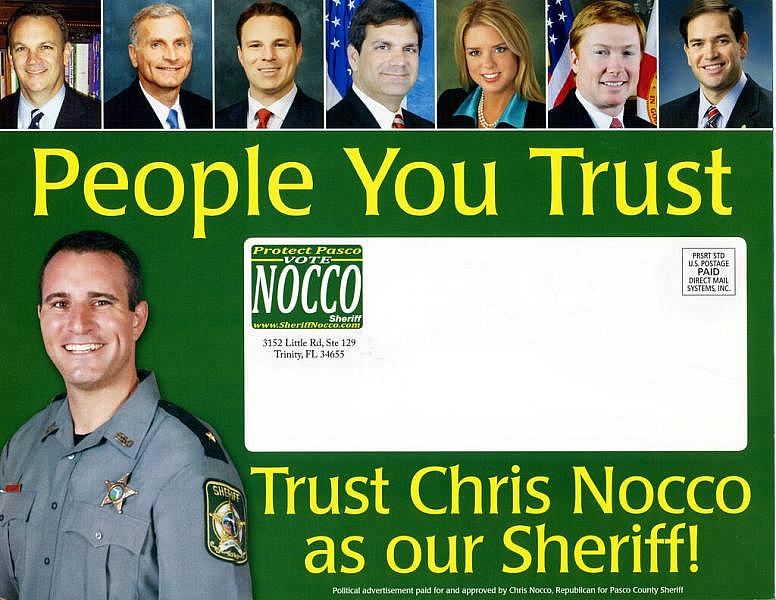

In Sheriff Chris Nocco’s first election in 2012, many of Florida’s most prominent politicians endorsed him.Times (2012)

As Rubio’s tenure in the state House was coming to an end, Nocco landed a $100,000-a-year civilian position with the Florida Highway Patrol.

Seven months later, White asked him to be a captain overseeing administrative areas for the Pasco Sheriff’s Office.

In a recent interview, White said he was looking for candidates with leadership potential. He described Nocco as tireless and intelligent. “He had no enemies in Pasco County,” White said. “He seemed like the right fit.”

Bridget’s career had also taken off. She had lobbied for powerful business interests, including HCA Healthcare and U.S. Sugar. And in 2010, she played a key role in the fundraising that helped land Scott, then an unknown businessman, in the governor’s mansion.

She did not return calls or emails from the Times.

In his statement, Nocco said: “I am very proud of my wife and the career she has built for herself.”

In the spring of 2011, White announced that he would be retiring before his term ended to spend more time with his family. As governor, Scott got to choose his replacement.

Some observers speculated White retired early so Republicans could handpick Pasco’s next sheriff. White told the Times that was just “a conspiracy.” Nocco has said he was unaware of White’s plans and came to Pasco because he missed being a sworn officer.

Regardless, just two years into his tenure at the Sheriff’s Office, Nocco was named the county’s top law enforcement officer.

Since then, his connections have continued paying off.

In 2012, Weatherford helped Nocco secure an additional $1 million in state funding for Pasco's child protective investigators while money for other counties stayed flat.

When Corcoran became speaker, he appointed Nocco to a high-profile board tasked with proposing updates to the state Constitution. Nocco used the post to introduce Marsy’s Law — a victim’s rights measure that police agencies, including his own, have employed to withhold the names of officers who use force.

His national profile only grew after 2016 when Ballard, already a powerful lobbyist in Florida, became influential in Washington.

This spring, Nocco was named to a 32-member panel that advises the secretary of Homeland Security on federal policy.

In July, he had a speaking role at a Trump re-election rally at Tampa International Airport that was carried on TV.

Ballard called Nocco a “political star.”

“Wherever he’s gone, he’s made friends, he’s served well and people think highly of him,” Ballard said.

Even after the Trump administration ends, Nocco will have powerful friends in Washington. Rubio is acting chairman of the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence and sits on the Appropriations and Foreign Relations committees. Scott serves on the Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs.

Both are considered 2024 presidential contenders.

■ ■ ■

‘WE FIGHT AS ONE’

Despite his limited experience in law enforcement, Nocco didn’t hesitate to reimagine the department after becoming sheriff.

The intelligence machine was just one piece of his vision.

He had the new motto — we fight as one — emblazoned outside headquarters, on police vehicles and on the patches on deputies’ uniforms.

He reshaped the command staff, making a series of hires with specialized military backgrounds, including a retired Army Special Forces colonel, a former Air Force intelligence analyst and a retired Navy captain who led SEAL teams and worked at U.S. Special Operations Command.

And he made a concerted push into code enforcement, doubling the number of tickets deputies gave for violations like overgrown grass, a Times analysis found.

The office also built a national following online. Today, it posts nearly every daylight hour, using a 26-page social media plan and hashtag glossary. The agency’s hundreds of thousands of followers get safety tips, cute dog pictures and nightly reminders to lock their homes at 9 p.m.

Some of the strategies have been more controversial. In 2016, the Sheriff’s Office made headlines for posting a photo of a man mid-arrest to its social media accounts under the heading “SAD CRIMINAL OF THE DAY.” Critics accused the department of ridiculing someone who had not been convicted of a crime and marginalizing people of color.

In one social media post in 2016, the Sheriff’s Office posted a photo of a man crying while he was arrested. Critics said the agency was publicly mocking people before they had been convicted. Facebook

“This criminal is not different than any criminal we post about every single day,” a spokeswoman said of the man, who was photographed in tears as two deputies grabbed his dreadlocks. “He was a threat to the community before. It's important the community know he is in custody and no longer a threat to them.”

In 2017, Nocco allowed the agency to be featured on the popular A&E reality series Live PD. Some deputies became overnight celebrities. But like its predecessor COPS, the show was criticized for glorifying aggressive policing.

Pasco ended its run on Live PD in 2019 after two seasons. The show was cancelled this year amid civil unrest over police brutality.

Over time, the Sheriff’s Office has grown. Although the number of sworn law-enforcement officers has increased about 15 percent since Nocco took office, the agency’s budget has risen 65 percent, to $142 million. (The department says its per-citizen cost of $294 still pales in comparison to the nearby Hillsborough and Pinellas sheriff’s offices.)

Body-camera footage obtained by the Times showed officers firing at an unarmed Black man during a small-scale drug bust in 2014. The video contradicted the reason deputies had previously given for the fatal shooting. Pasco Sheriff’s Office body-camera footage

Nocco says property crime has gone down. But the reduction — which his office credits to its intelligence efforts — is similar to the decline in the seven-largest nearby police jurisdictions. Violent crime has gone up only in Pasco.

For years, community activists have raised concerns about what they consider to be over-aggressive policing.

That same month, Marques Johnson, a hip-hop artist who performs under the name Andre Roxx and is Black, filed a federal lawsuit alleging deputies violated his civil and constitutional rights by arresting him without probable cause in 2018. A Live PD crew was in tow, according to the suit.Most recently, in June, a 2014 incident in which deputies shot and killed an unarmed Black man received new scrutiny when the Times obtained body-camera footage that contradicted the agency’s justification for opening fire.

At the time of his arrest, Johnson was a passenger in a car driven by his father. Deputies stopped the vehicle because it had an obstructed license plate. When Johnson declined to identify himself, citing his Fourth Amendment rights, the deputies arrested him for resisting an officer and obstructing without violence. A judge later dropped the charge.

“The default approach at that agency is an aggressive, hostile approach,” said Johnson’s lawyer, Ryan Barack.

The Sheriff’s Office is seeking to have the suit dismissed. It has said that it determined the deputies acted appropriately.

Internally, deep divisions have opened up within the department.

In April 2019, two former deputies and a civilian manager sued Nocco in federal court, alleging they had faced retaliation after reporting misconduct. Since then, another 16 former deputies have sued with additional claims of corruption.

The department has fought the allegations publicly and accused the plaintiffs of protocol violations ranging from insubordination to having sexual relations with a confidential informant.

Some of the allegations and counter-allegations are near-impossible to unravel and cast both the plaintiffs and the Sheriff’s Office in a negative light.

But some are jarring, coming from high-ranking officials who left the agency.

Former Intelligence Led Policing Manager Anthony Pearn, who holds a doctorate and once worked for the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, described in court papers a case in which agency leaders used the intelligence apparatus to try to arrest someone who posted a mugshot of a deputy on Facebook.

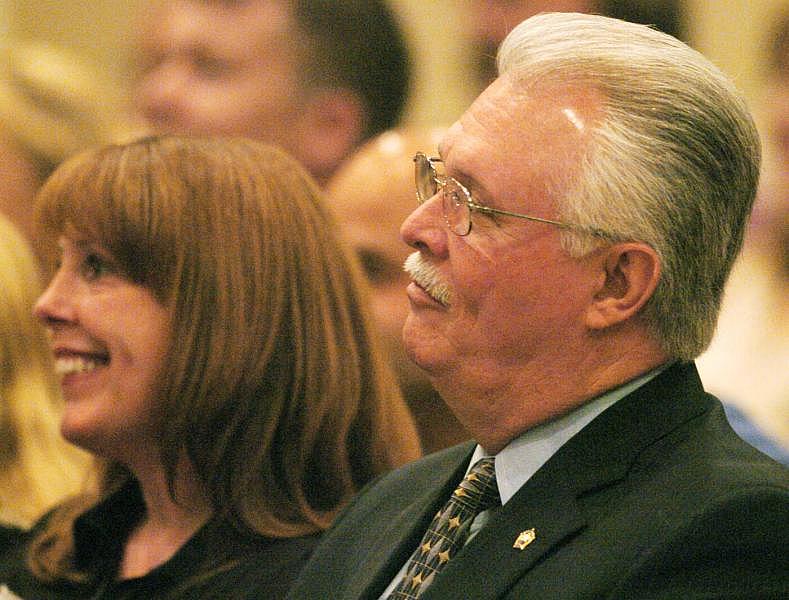

Then New Port Richey Police Chief James Steffens talks with a lieutenant after a SWAT team operation in 2012.Times (2012)

The Times reviewed the Internal Affairs investigation into the incident, which found that the intelligence arm looked into a woman — a known white supremacist — and her family after she posted an old booking mugshot and address of a deputy who had been featured on Live PD.

Agency leaders told Internal Affairs that they did subsequently target the woman and her family. But they said it was part of a separate drug investigation and called the timing coincidental. Internal Affairs determined there had been no wrongdoing.

Pearn declined to comment.

Former Capt. James Steffens, who Nocco wooed to the Sheriff’s Office from his previous post as New Port Richey police chief, said that he and most other command staff members were required to make big donations to the sheriff’s 2016 campaign: $1,000 in their own names and $1,000 in their spouses’.

Steffens said members of Nocco’s command staff and their spouses were required to donate $1,000 to the sheriff’s campaigns. DOUGLAS R. CLIFFORD | Times

The Sheriff’s Office said contributions were not mandatory. Campaign finance records from 2016 show that 13 out of 16 of Nocco’s captains, majors and colonels — including Steffens — gave $1,000, the maximum contribution in a countywide race. Many of their spouses also contributed $1,000. The pattern continued in 2020. In both years, Nocco was unopposed and gave the money he didn’t spend to charities or the Sheriff’s Office.

Steffens, a biracial Black man, also has a lawsuit against the department alleging he faced systemic racial discrimination at the agency. It claims Nocco forced Steffens’ resignation, then used the media to humiliate and defame him.

The agency has said that it accepted Steffens’ resignation over leadership lapses related to charges that one of his deputies tampered with evidence.

DECLINING TO COMMENT

In a meeting during his first year in office, Sheriff Chris Nocco explains the agency's new focus on intelligence-led policing. Times (2011)

For years, Nocco has touted his intelligence operation at community meetings and in campaign materials.

But when the details of how it actually worked became public, national experts were stunned. Two academics who the Sheriff’s Office said helped develop the program each disclaimed any responsibility for it. Others likened the tactics to harassment, child abuse and policing that could be expected under an authoritarian regime.

Meanwhile, state and county leaders — virtually all Republicans — have avoided saying anything of substance about the program.

Pasco County Commissioner Jack Mariano said he hadn’t read the Times’ investigation but fully backed the Sheriff’s Office. Commissioner Ron Oakley said he also hadn’t read the investigation and declined to comment.

The three other people on the commission in September — Mike Moore, Kathryn Starkey and Mike Wells Jr. — didn’t return reporters’ calls.

Neither did Christina Fitzpatrick, who joined in November.

Nor did the state’s legislative leaders: Senate President Wilton Simpson, who represents parts of Pasco, and House Speaker Chris Sprowls, a former prosecutor in the judicial circuit that covers the county.

Pinellas-Pasco State Attorney Bernie McCabe also didn’t return calls.

Asked about deputies harassing some of his clients, outgoing Public Defender Bob Dillinger said none had mentioned it.

Attorney General Ashley Moody’s office said it does not oversee independently elected sheriffs but noted that the governor could assign the Florida Department of Law Enforcement to review the program. The Florida Department of Law Enforcement said it does not have oversight over local agencies. Gov. Ron DeSantis did not answer questions.

U.S. Rep. Gus Bilirakis, who represents all of Pasco County, didn’t have time to read the Times’ investigation, his spokeswoman said in September. Asked again in December, he said in a statement that he “didn’t pretend to know enough about Pasco’s intelligence-led policing program.” He added that Nocco is “a good man and dedicated public servant.”

When the Times revealed the Sheriff’s Office uses confidential school-district data to identify kids at risk of becoming future criminals, schools Superintendent Kurt Browning called the sheriff “a great partner.” Two board members, elected in nonpartisan races, praised the district’s relationship with the Sheriff’s Office.

When the Times revealed the Sheriff’s Office uses confidential school-district data to identify kids at risk of becoming future criminals, schools Superintendent Kurt Browning called the sheriff “a great partner.” Two board members, elected in nonpartisan races, praised the district’s relationship with the Sheriff’s Office.

Browning — a Republican with a long history in state politics — later defended the school district’s practice of sharing its data with law enforcement, saying it helps keep schools safe. He didn’t address experts’ concerns that the arrangement could violate federal law, didn’t answer teachers’ questions about why the program was allowed to operate in secret and implied the Times’ reporting was misleading.

The only contrary view came from state Sen. Jeff Brandes, a St. Petersburg Republican and chairman of the Judiciary Committee. He asked on his Facebook page if children’s school grades are covered by the Fourth Amendment. “If not, they should be!” he wrote.

The Sheriff’s Office remains defiant.

“We will not apologize for continuing to keep our community safe,” it wrote on Facebook in September, after the Times' initial report.

“Misinformation has recently been shared about these important programs and facts matter,” it posted in December, after Pasco parents and teachers began demanding a review of its use of student data.

On his personal Twitter feed, Nocco has continued projecting tranquility.

On Dec. 7: “Stay firm.”

On Dec. 14: “You will never influence the world by trying to be like it.”

On Dec. 17: “As long as you know God is for you, it doesn’t matter who is against you.”

**

Times staff writer Josh Solomon contributed to this report.

The Times reported this story with the support of the Fund for Journalism on Child Well-Being, a program of the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2020 National Fellowship. The reporting was also supported by a grant from the Fund for Investigative Journalism.

[This story was originally published by The Tampa Bay Times.]