Teen birth rates are highest in our poorest neighborhoods. But they affect all of us

This story is part of a series about sex education and teen pregnancy, and is produced as a project for the USC Center for Health Journalism’s California Fellowship.

Other stories in the series include:

Sex education is now the law, but conservative school leaders aren’t happy about it

Why are birth rates higher for Latina teens than others? It’s complicated, experts say

This teen mom and her newborn rode a city bus to a school for delinquents. Here’s why

At 14, she was told to hide her baby bump and switch schools. Her shaming wasn’t unique

After reading teen mom’s story, strangers wanted to help. And they delivered.

Sandra Flores, program director for the Fresno County Preterm Birth Initiative, addresses those gathered for a health and education meeting Tuesday, Sept. 12, 2017 in Fresno.

It’s about a 15-minute drive from McLane High to Buchanan High, but the difference in teen birth rates within the schools’ respective ZIP codes is staggering – and alarming.

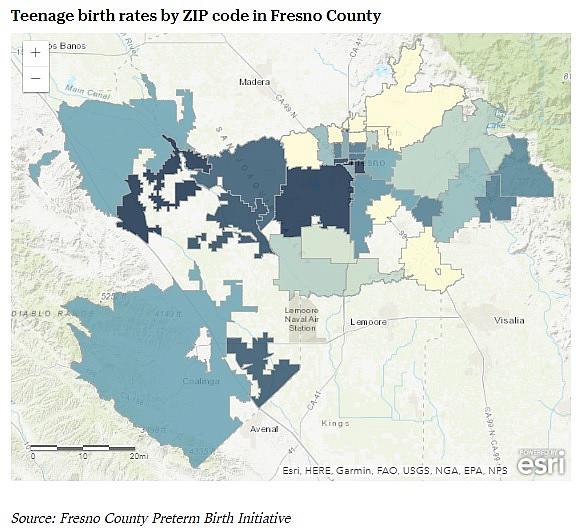

Buchanan High, a Clovis Unified school, is in Fresno County’s 93619 ZIP code, where less than 1 percent of teenage girls gave birth between 2011-2014, according to the Preterm Birth Initiative (PTBi.) About eight miles south, in a ZIP code home to Fresno Unified’s McLane High students, more than 10 percent of girls had babies during the same time frame.

Teen birth rates aren’t the only differences between the neighborhoods of the two schools. At Buchanan High, more than half of the student body is white, and less than 30 percent live in low-income households. At McLane High, 96 percent of students are considered low-income, and only 3 percent are white.

Poor communities of color “are bearing the burden” of a slew of health issues, said Sandra Flores, program director for Fresno County’s PTBi. But the disparities related to the reproductive health of the city’s youth is especially concerning, she said, stalling education and contributing to cyclical poverty.

“We really have to start having these conversations around equity, and understand that when we continue to ignore or marginalize those communities, we collectively suffer,” Flores said.

“Nobody goes unaffected by these kind of rates … All of these teen moms having babies right now, they’re filling kindergarten classrooms in five years. We can’t look at this issue in isolation.”

Six of the 10 California counties with the highest teen birth rates are in the Central Valley, which also is home to the state’s highest rates of sexually transmitted diseases. While a new state law mandates comprehensive sex education, requiring schools to teach about pregnancy and STD prevention, health experts say it will take more than that to fix the region’s teen birth rates – which range widely, depending on where teens live.

The lowest teen birth rate in Fresno County is 0.7 percent in northern Clovis, where the median household income is about $105,000. The highest rate is in Biola, a small, predominantly Hispanic community west of Fresno, where 11 percent of teens gave birth. The median household income in Biola is about $23,000, below the federal poverty line.

Flores said while sex education is “extremely valuable,” those disparities mean it’s not enough.

“The education without the access means nothing,” Flores said. “If we want to take historically distressed communities and create communities of opportunity, we have to give young people what they need – and the access to it.”

Kayla Wilson, who teaches sex education for the Office of the Fresno County Superintendent of Schools, works closely with Latina teen moms. She explains to her students that birth rates may be disproportionate because white, affluent girls are more likely to get reproductive services.

“They’re going to clinics. They have transportation. They have more of a means to get birth control,” she said. “I don’t think we have ingrained in women that for them to get out of that poverty means to be in control of their own rights – and the right to be able to dictate when they want to have children. But we don’t help women access that.”

That’s one reason why the Condom Access Project was created. The program mails condoms to teens across California in unmarked envelopes to the address of their choice, warning that it’s not a promotion of teen sex, but a solution to a lack of transportation, access to clinics or fear of seeking out resources.

Nearly 100,000 free condoms were distributed in Fresno County last year through the project’s home-mailer program and to “condom access sites” like Fresno Barrios Unidos.

“There are a few things at play that all create a pathway for these disparities to exist,” said Amy Moy, vice president of public affairs for Essential Access Health, which oversees the program. “We started the Condom Access Project because we saw the research showed that youth were being disproportionately impacted by STDs and unintended pregnancy when it comes to geographical regions. Part of the reason for that was concerns about confidentiality and cost, so we wanted to eliminate both of those barriers if they are going to be sexually active.”

The health disparities in Fresno are “not new, and not by accident,” according to John Capitman, executive director of the Central Valley Health Policy Institute.

“Places like Fresno systematically made policy choices that created and sustained inequality. We have a long history of creating inequality,” Capitman said. “No matter what the topic is, people who are more affluent and live in more health-supportive communities have better health outcomes all across the lifespan. It’s a really hard reality for everybody, but to meet the goals the city has for itself, we have to take that on.”

I don't think we have ingrained in women that for them to get out of that poverty means to be in control of their own rights - and the right to be able to dictate when they want to have children. - Kayla Wilson, Office of the Fresno County Superintendent of Schools

Health experts hope the addition of six school-based health centers, which Fresno Unified approved earlier this year, will ease some of these problems. The district currently only has one such health center, located at Gaston Middle School, that offers birth control and gynecological services.

As of 2016, only one of the school-based health centers in Fresno County offered reproductive health services: Parlier High. Nearly 99 percent of Parlier High students are Latino, and 94 percent are low-income, but the area’s teen birth rate is not nearly as high as others with similar demographics. In Parlier High’s ZIP code, 5 percent of teen girls had babies in 2011-14.

Alejandra Saldivar from Barrios Unidos asks a question during the Fresno County Preterm Birth Initiative’s health and education meeting Tuesday, Sept. 12, 2017 in Fresno.

A Fresno Unified spokeswoman said that all of the incoming health centers will offer reproductive services.

Jennifer Day, a nurse who coordinates Fresno County’s Maternal Child and Adolescent Health program, said the county has a lot of positive momentum with respect to reproductive health, but there are still barriers that can impact the health of both mother and baby. Day said she has seen how a resistance to sex education and a lack of access to care can delay prenatal care for teen moms.

“We see young moms wearing baggy clothes to hide their bellies quite often, and they’re almost 30 weeks before the word gets out,” she said. “They end up going to the ER because they’re sick, and then get an ultrasound and lo and behold, they’re pregnant.”

A simple solution

The neighborhood a child grows up in may be the biggest contributor to teen pregnancy rates, according to Capitman.

“The growing-up experiences of a woman may influence the health and well-being of her child, and the growing-up experiences of the child are shaped by the neighborhood in ways that express themselves throughout the life course,” he said.

Capitman, Flores and Mara Decker, a researcher at the University of California, San Francisco who specializes in adolescent sexual and reproductive health, point to a surprisingly simple solution for curbing teen birth and STD rates: after-school activities.

Decker, who does research in the Valley, said there’s no single answer to explain the local health disparities, but providing structure to teens in needy neighborhoods is a start at lessening it.

“In communities where they feel like they have options, where there are after-school activities and jobs available, they are more likely to have opportunities to move forward,” Decker said. “It’s about what kind of information they are receiving at their schools and what kind of support they’re getting from their families and neighborhoods.”

Places like Fresno systematically made policy choices that created and sustained inequality. - John Capitman, Central Valley Health Policy Institute

Providing options also means giving teens something to care about – something they wouldn’t want to risk losing by becoming a parent, she said.

“In communities where those opportunities are more restricted, sometimes having a baby doesn’t actually make that big of a difference. It’s like it doesn’t even matter,” Decker said.

“Oftentimes, we think of teen pregnancy as unplanned, but having a baby is a planned event for some of these young women – to have someone love them, or to get out of their neighborhoods or out of their house.”

When President Donald Trump proposed budget cuts to federally funded after-school programs earlier this year, Fresno Unified vowed to use its own money to maintain the programs in case they were eliminated.

Jeff Hunt, top left, and Alma McKenry, top right, lead the discussion during Fresno County Preterm Birth Initiative's health and education meeting Tuesday, Sept. 12, 2017 in Fresno, CA.

Sally Fowler, who oversees Fresno Unified’s extended learning programs, said that’s because the district can’t afford to lose that after-school time with kids. School officials ask students what they want in a program – whether it’s hip-hop class or cooking courses – and give them that to get them there.

The programs mean participating children – who may be exposed to violence or don’t have parents at home – are too busy to engage in risky behavior, she said. The activities also help promote equity.

“We have very diverse families, and there’s a gap in the opportunities their parents are able to offer,” Fowler said. “After-school programs are a bit of an equalizer.”

Breaking down resistance

Even as Fresno is experiencing a syphilis epidemic, concerns are swirling about the California Healthy Youth Act and whether it’s appropriate for schools to teach in-depth lessons on sex education.

Flores scoffed at the irony.

“It’s such an atrocity,” she said. “We are seeing an astronomical increase in a disease that is completely prevented with condoms, and we have young people with the courage to ask for them, but adults aren’t supporting their decision. And it is not our decision to make.”

The Valley has a history of resisting sex education, infusing an already complicated health problem with politics and religion. Flores said the Healthy Youth Act has her hopeful, but “we have this disconnect” between what the law mandates and what supports are actually in place in schools.

Time and time again we have cases where teens come to a clinic and they are either dismissed or treated with disrespect. - Mara Decker, UCSF researcher

Fresno Unified’s school board voted unanimously last year to have teachers undergo comprehensive sex ed training, but board president Brooke Ashjian is under fire for his opinions on the matter. Ashjian spoke out against the inclusion of LGBT relationships in the curriculum and has been a critic of sex education in the past, opting his own children out of the courses.

“We all want the same thing: for our young people to make good decisions, and to be healthy. We have a shared future as community members,” Flores said. “But how we support our young people in that is a much more complex conversation. Whether it’s lack of information, lack of access, or lack of a significant adult in their lives, our systems are not working at maximum capacity, and are allowing our young people to slip through the cracks.”

A survey of more than 300 teens in the Central Valley conducted by Essential Access Health earlier this year showed that interactions with some providers can actually act as a barrier to teens seeking care or practicing safe sex.

“What we heard was that there would be judgment and biased care in health centers. Youth in the region said they had experienced people saying things like, ‘You’re too young to have sex so we don’t need to talk about this,’ ” Moy said. “A lot of the solutions needed have to be community-driven.”

In her research, Decker sees this “all the time,” whether it’s a pharmacist or a front office assistant.

“Time and time again we have cases where teens come to a clinic and they are either dismissed or treated with disrespect,” she said. “We have to make sure that there are clinics where youth feel comfortable. It’s a huge barrier if you get your courage up to go, and then the provider speaks down to you. You’re not going back.”

[This story was originally published by The Fresno Bee.]

[Photos by Eric Paul Zamora / The Fresno Bee]