The trust-builder: a cancer center director’s try-it-all strategy for breaking the barriers between research and Black patients

This series was supported by the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2022 Impact Fund for Reporting on Health Equity and Health Systems.

Other stories in this series include:

Community members listen to VCU Massey Cancer Center Director Robert Winn during his district walk in late March in Highland Springs, Va.

CARLOS BERNATE FOR STAT

RICHMOND, Va. — The residents agreed: Nobody like Robert Winn — director of the Virginia Commonwealth University Massey Cancer Center — had ever visited the neighborhood before. This development on the outskirts of Richmond, more parking spots and asphalt than trees and lawn, was “the hood,” after all, they said. “This neighborhood — it’s been so long since we had anybody who even cares to come,” said Glenda Barnhart, a 68-year-old resident. Certainly not anybody from the big hospital.

And now, not only was this doctor with a cheesy grin and a bouncy step before them — he’d also brought along several local officials, including their county manager. At first it seemed that Winn, a pulmonologist-oncologist who calls himself first and foremost a bench scientist, had come to the squat buildings at the Coventry Gardens apartments to talk. But Winn had come to listen.

“That’s the most important thing,” he said. “Making sure that we get to hear. We scheduled this to make sure that I’m hearing you — like, what are your needs.”

Since Winn became the director of the Massey Cancer Center at the end of 2019, he’s tried to visit a neighborhood — particularly low-income, rural, or ethnic minority neighborhoods — in one of the 66 towns, cities, or counties that his hospital serves at least a couple times a year. He calls them district walks. It’s one of the cornerstones of an overarching strategy he calls “high tech, high touch.”

High tech, he said, is the wave of advancements in cancer that have revolutionized care. High touch are the personal interactions, often face-to-face, that he’s using to overhaul the way his academic medical institution interacts with marginalized communities. That includes meeting local and state representatives, greeting patients in the community when they go to his hospital for care, taking part in community events, and more. That contact, he hopes, will build trust, reduce health inequities, and increase diversity in clinical trials — a key part to both advancing science and ensuring the most state-of-the-art medicine is accessible to all patients.

“If you’re a minority in this country, it would be abnormal for you not to be suspicious of the health system,” Winn said in an interview after the district walk. “If we have the ability to be mindful of the nature of what that is and how to overcome that, we’re going to see a lot more positive results and — yeah — a lot more people on clinical trials. My district walks was to do two things: start building the foundational blocks of trust. People tend to trust you when they know you. Then, for me to get to see what really are the realities on the ground.”

What Winn learns from listening to people on these community visits has transformed into an eclectic array of projects that he spends both workdays and free time on. He’s thrown his energy into housing development, seed grants for community projects, influencing policy, building new health services at the Massey Cancer Center, and building close relationships with community organizations.

It’s an approach that health equity experts called both unusual and likely to make a lasting impact in health disparities. “It’s what we need to make a difference,” said Adana Llanos, a cancer researcher at Columbia University. “Not just novel, but innovative ways to address disparities.”

At Virginia Commonwealth University, which operates Massey Cancer Center, Winn’s up against quite a challenge. People of color, particularly Black folk, have long held a dim view of VCU Health — ever since the days it was called the Medical College of Virginia and it ran a separate “colored-only” hospital called St. Philip. This was the institution that performed one of the world’s first heart transplants from a Black man without his or his family’s consent and gave it to a white man. It was also the place that robbed Black graves for medical cadavers.

But you can’t build trust without showing up in person, Winn said. So, standing in the neighborhood’s packed community room and looking like anybody’s dad in a light green jacket and khakis, Winn introduced himself.

“Some people are sometimes surprised. They’ll say, well, you a cancer doctor. How come you sound – Well, I sound exactly like I sound because I’m actually proud of the people I came from. Period.” Winn said. “I came from a teenage mom, just being straight up. Didn’t think about being a doc. I was thinking of working at GM. I’ve learned how to put on a blue blazer and a bowtie, but at the end of the day if all we’re doing is sitting up there right at College Street up in Richmond and ain’t really think about how we’re getting out to the neighborhoods then this ain’t gonna work.”

With his district walks and relentless community outreach, Winn could be mistaken for a politician. He opens every community visit with something akin to a stump speech. He’s a natural orator, pulling the audience in with jokes and stories while promising to serve the community. Then he launches into a litany of statistics, starting with the fact that nearly a third of all adults will get cancer at some point in their lives — and Black Americans are more likely to die of cancer than any other racial group.

“Number one on the list for breast cancer: African American women. Number one on the list for prostate cancer: African American men. Number one on the list for lung cancer, GI cancer, pancreas,” Winn said. “Put it this way, most of our communities ain’t doing well. So while I’m here with breath in my body and the resources at my position, I’m just trying to figure out how we can work to do something better. That’s what this conversation is about.”

Rev. Delores L. McQuinn of the Virginia House of Delegates (left) speaks to community members during one of Winn’s district walks in Varina, Va. CARLOS BERNATE FOR STAT

To Winn, clinical trial diversity is a barometer of health equity in cancer because so much must be in place before someone can actually participate. People must be considered for trials in the first place, Winn said. Then they must have a battery of needs met to actually participate. That often includes transportation, stable housing, paid sick time, child care, and sometimes even certain health insurance.

“How do you treat someone with a drug if they have an unstable housing issue, and they can’t even come back for the therapies?” Winn said. “All of these things are critical to reducing the cancer disparity gap.”

The data on racial minority participation in clinical trials are abysmal, despite the issue being considered a priority by the National Academies and federal research agencies like the National Institutes of Health. In a review of 662 clinical trials in oncology, researchers from the University of California, San Francisco, found that 91.7% of the nearly 50,000 participants were white. Asian, Black, and Hispanic people represented 1.5%, 2.6%, and 1.7% of trial participants, respectively. Winn sees such figures as a sign that society and the health system are failing across the board when it comes to equity.

That’s much different from the popularly held view, said Vanessa Sheppard, a cancer disparities researcher at VCU and the Massey Cancer Center. Often, academics explain the gap between Black and white participation in trials by pointing to famous atrocities like the Tuskegee syphilis study, where treatment was withheld from Black syphilis patients without their consent. But reality, Sheppard said, is much more complex.

“We want to pinpoint, ‘Oh it’s just because of Tuskegee. It’s just because of this other thing,’” she said. “And we’ve done a great job educating the public about certain things that have occurred, but most folks didn’t know about this until they saw the movie or read the book. Henrietta Lacks? That wasn’t widely known.”

Instead, Sheppard said the roots of mistrust are multifaceted. Historical trauma may make up one part of it, but Sheppard found in her work that personal experiences of discrimination are often more salient when it comes to mistrust. “Everyday experiences that people have, the interactions that you have with our institutions, the schools, all of health care, and how you treated me yesterday at the doctor’s office, that’s what matters,” she said.

That means one of the most important things when it comes to facing mistrust is simply building strong rapport between providers and patients, Sheppard said. “What overcomes that in terms of your decisions about your health is your relationship with that health care organization, those physicians, and how the staff treat you,” she said.

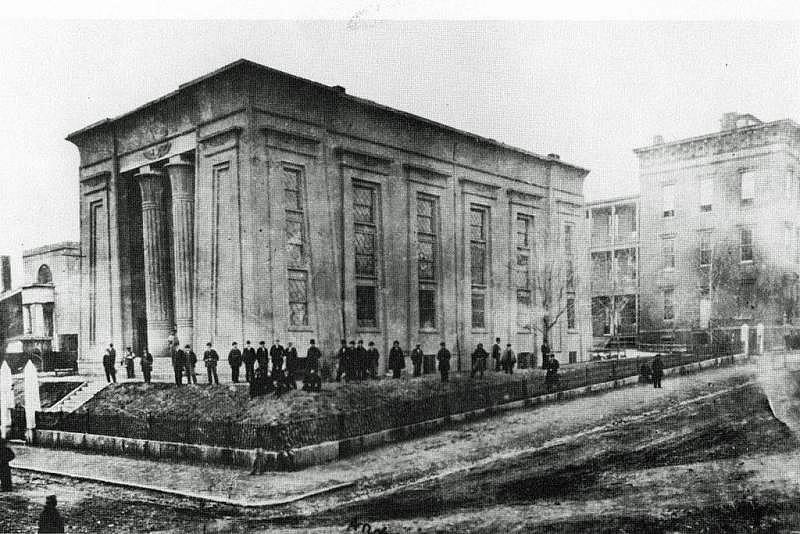

In 1994, VCU was building a new science center when it ran into an unmarked mass grave. Heavy equipment dug into the ground beside one of VCU’s oldest buildings: the Egyptian Building. With walls of sandy yellow stucco, the front is guarded with two massive columns that makes the building look more like the temple of an ancient god than medical classrooms. Buried at the feet of the Egyptian Building, the construction crew discovered a circle of red, handmade bricks that encased dozens of human skeletons.

It was an old well, dating back to the 1800s, and an archaeological analysis showed that nearly all of the human remains were of African descent. They were medical cadavers, robbed from nearby graveyards and used for the Medical College of Virginia’s doctors in training to learn anatomy. When the students finished their dissection, the college dumped the bodies into a dry well by the Egyptian Building.

The discovery rolled through the college community like a shockwave. Scholars pointed to it as another example where Black people had been abused by academic medical institutions — Richmond’s Tuskegee. In a documentary, Shawn O. Utsey, the chair of VCU’s department of African American studies, found that longtime Black Richmond residents remember being told not to walk by the Egyptian Building at night. They might be snatched up by the “night doctors” and never seen again — an urban legend grounded in a racist reality.

Yvonne Bibbs, a pastor who’s worked at the Sixth Baptist Church in Richmond for 20 years, didn’t know that VCU had exhumed the abandoned bodies of African Americans. She hadn’t heard the history behind VCU’s racist past — but when she learned about the grave robbing, Bibbs just shook her head lightly. She wasn’t surprised.

“You’re in Richmond, Virginia, the capital of the confederacy,” she said. “If you walk down streets in downtown Richmond, you will find there are many places made by slaves. The bricks are still there. I think that’s enough said.”

It’s another story — like so many others — that reinforced a betrayal evident to many Black people. Their hands had built roads and buildings of the city. Their bodies had been used in science that advanced medicine. Then, they’d been left behind like trash. In a system with centuries of racism, the atrocities are often familiar.

Finished in 1845, the Egyptian Building served as the first medical education building for the Medical College of Virginia and included a dissecting room. WIKIMEDIA COMMONS/VALENTINE MUSEUM

Teressa Burrell, a 65-year-old woman who’s lived in the Richmond area all her life, hadn’t heard of the old well full of bones on VCU’s campus. There were some things she heard growing up — maybe different versions of the same thing, she speculated. “There was stories that bodies were taken from the morgue without people’s consent,” she said. “I heard that they used Black people or people of color for testing like guinea pigs.”

Yet she didn’t feel any of those stories were why she’d been suspicious of MCV as a patient. She’d gone to the hospital throughout her life, as had many members of her family, for care, and she felt the doctors had been arrogant and discriminatory. She always tries to go somewhere else for care if she can help it.

“They were very rude, you know? I don’t feel like I was treated fairly,” Burrell said. “Sometimes, it’s not always just because you have a Black face. Sometimes, it’s the way you came in — like a person with prestigious insurance versus a person with Medicaid.”

But as she listened to VCU’s Winn talk at the Coventry Gardens, near where she lived, she found her mind changing about the hospital. This cancer center director — the first Black president-elect of the Association of American Cancer Institutes — had taken his time to talk to them and listen to them. He talked about genetic testing and counseling for cancer genes, building programs for students and young scientists of color, and fresh foods for the neighborhood. It delighted her.

“He was just different. He was down to earth, informative,” Burrell said. “It was the sense that we’re being heard — the community. Someone’s thinking about us. Someone cared about us. And, you know, we do exist.”

Burrell said that feeling extended to her attitudes about participating in clinical trials — if they came from Winn or one of his researchers. “I’d be interested in learning more,” Burrell said. “Because he explains things, you know? He allows you to ask questions, which is very important because this is my body, and I want to know why are you doing this research? What’s it about, and who’s it going to benefit?”

As long as any researcher took the same time, said Barnhart, also a resident in the same neighborhood near Richmond, she’d be willing to consider any clinical trial. It all comes back to the same thing, she said. “Explain.”

It wasn’t until Winn was going through his medical training that the importance of cancer clinical trials really clicked for him. Initially, he saw trials as a way of gathering evidence showing if a new drug or intervention was working. As he became a doctor, he realized that when the current available treatments failed, clinical trials were where patients could access the most cutting-edge medicine and technology to give them one more, if unlikely, shot at survival.

“Really, it’s an extension of the standard of care when the standard of care ain’t working. Because in the world of cancer, there is no placebo,” Winn said. “It isn’t just an experiment. It’s giving you additional hope, an additional way of fighting your cancer.”

As a med student and a trainee, Winn fell in love with science and the ability to investigate next-generation interventions that might offer that extra chance. He was good at it, too, but something had always bothered him. “We’ve been thinking about the bench to bedside model for so long, and I always thought there was flaws with that,” he said. “If people can’t get to your bedside, they’re not getting any benefit from the research that you’re doing at the bench side.”

For so long, Winn felt that the most cutting-edge advances in science and medicine were generally benefitting the most well-off individuals in society. White, wealthy, and urban people were the ones with the knowledge and the wherewithal to learn about clinical trials, be represented in them, and reap the benefits. Meanwhile, people of color, low-income people, and rural people were cut out.

In other words, his people were being cut out, Winn said. He grew up around the east side of Buffalo, N.Y., in the ’70s and ’80s. “It was a hard place. It would be dangerous being a Black person going into predominantly white areas. That was real,” Winn said. His grandmother cleaned houses, and many of the men in his family worked in auto manufacturing. When two of his uncles were hit with prostate cancer, clinical trials were not part of their treatment. “My grandfather, my father, my uncles, they were the people I was most impressed by. They got up, pain every freaking day, getting out there to work. Blue-collar guys.”

Winn grew up to get a white coat. He went to Notre Dame University, University of Michigan for medical school, Chicago for his residency, and then the University of Colorado for fellowship. Throughout it, he saw some of his other students and trainees of color start to “lose themselves,” he said. “They change because the pressure is to say, you’re not good enough, so you must assimilate.”

But as a Black kid in the ivory tower, Winn was still comfortable with who he was. Instead, when white or wealthy professors or colleagues would talk about diversity in health sciences, Winn felt they were the ones pretending to have knowledge only he had. “Here’s the language over the last 30 years: ‘Those people in those neighborhoods are not on our trials,’” Winn shook his head. “Yeah, yeah. OK. So, people ask me if I ever had imposter syndrome. I always say, an imposter to what? You don’t know my hood. I know yours. I lived in it. Notre Dame, Michigan, all the rest. I don’t try to play. I’m just trying to be who I am.”

Throughout his career, Winn was looking at the big picture, said Talmadge King, the dean of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, and one of Winn’s advisers when they were at the University of Colorado. “We didn’t use the word ‘health equity’ back then, but his whole interest was trying to figure out ways to take medical advances and making sure they were equally applied to everyone in need,” King said.

As a fellow, Winn wanted to do whatever he could to advance that ideal, King said, and it led to his taking on as much as he could. Winn took on additional roles including associate dean of admissions and vice chair of career development and diversity inclusion. “He was doing basic research in a lab, and then the next day he was head of admissions for the medical school. Like — wow — those are very different things. He was so committed to both and able to do it almost seamlessly,” King said. “He just felt very strongly about being in a position to give back.”

He’s gotten there, but it hasn’t come without a cost. Winn said his marriage ended because he worked around the clock.“The reality is that it’s hard to be married to someone who sees this work as their life’s calling. So, that ended amicably. But definitely, I’m good to go, man. I’m happy as hell. I take care of a cancer center,” Winn said.

With his position, Winn said, comes a platform to make meaningful changes. “I think I’m a solid researcher,” he said. “But as a cancer center director, I can have a lot more impact.” As director of the Massey Cancer Center and, beginning in 2023, the president of the Association of American Cancer Institutes, Winn has the power to begin transforming the way the cancer field understands diversity in clinical trials.

“We have to go beyond just designing clinical trials and implementing trials to understanding the whole community,” he said. To Winn, that means looking deeply at all the factors that prevent someone from being able to focus on their health or cancer treatment — from lack of transportation and homelessness to simple awareness of trials and medicine — and doing something about it.

To tackle those issues, Winn uses his clout as a VCU center director, the largest employer in Richmond and one of the most important organizations in Virginia, to pull politicians, housing developers, and state and county officials. He brings them to his office to discuss policies or programs that he believes will improve health equity and cancer outcomes. He takes them out on his district walks to listen to people’s concerns about their health and cancer firsthand.

“He talked about cancer in a way that you are gonna need to engage the community and strongly consider the research and be part of the research,” said Delores McQuinn, a democratic Virginia state delegate who has accompanied Winn on district walks. “Help people understand that we are making so many advancements through research and studies so it doesn’t have to be a death sentence. So prevention and intervention and resources are made available, and people understand that.”

Then, Winn bends their ears on policies as wide ranging as improving internet access (“for telehealth,” Winn pointed out) and funding for genetic testing and training for genetic counselors of color in the state.

“Dr. Winn and I had conversations about all of those things. What do we need to do? How can we better serve with resources, with education, in communities where disparities have existed for so long?” McQuinn, who is a breast cancer survivor as well, said, “Just having him as a resource, as a voice, to address policy with other organizations I work with helps focus on what as a legislator can I do, and how I can be a good partner.”

Winn’s also used his position as the cancer center director to build up an office of community engagement and outreach at the Massey Cancer Center. That office has begun offering free health counseling by phone to residents, running cancer screening programs, and created community seed grants to fund projects that support neighborhoods around Virginia. Even outside of cancer, Winn looped in faith leaders around Richmond including Sixth Baptist Church’s Bibbs to create an online forum called Facts & Faith Fridays during the pandemic. That helped disseminate Covid-19 prevention and vaccine information to the public and brought in heavyweight speakers like the National Institutes of Health’s Anthony Fauci.

That signals to communities of color and low-income communities that he — and the Massey Cancer Center — are invested in them, Winn said. “So much so that you’re willing to put in resources, willing to hire people from those communities,” he said. “It’s not just about convincing them to be on clinical trials. That’s not their problem; it’s our problem.”

Rev. Dr. Yvonne Bibbs delivers a sermon during a March Sunday service at Sixth Baptist Church in Richmond, Va. Winn partnered with Bibbs to create an online forum called Facts & Faith Fridays during the pandemic. CARLOS BERNATE FOR STAT

Every researcher concerned with diversity and health equity in clinical trials has, at some point or another, learned the same thing, said Jonathan Jackson, a neuroscientist and director of the Community Access, Recruitment and Engagement Research Center at Massachusetts General Hospital. “A recent National Academies report found this, too. The way you get minorities into research is just by asking them,” Jackson said. “Just ask. In order to ask them, you have to show up. If you can show up, that’s enough to move the needle. But what Dr. Winn is doing goes beyond that in lots of wonderful ways.”

What “just asking” doesn’t do is provide the housing, transportation, child care, lost income, or health insurance that many people need in order to take part in clinical trials. When access to those things suffer, clinical trial diversity suffers. The reason those often aren’t available in low-income communities and communities of color, Jackson said, is connected to multiple systems of inequity. “It’s not hard to see there’s a very direct connection between the diversity of a research protocol, and the larger landscape of health disparities in the communities you recruit from,” Jackson said.

Most scientists don’t — or can’t — tackle systemic problems like housing or food insecurity. Instead, Jackson said trying to attain high levels of diversity often feels like playing whack-a-mole with all these different issues. “Systemic problems call for systemic solutions. The problem is most of us don’t have the reach, infrastructure, buy-in, or resources to make that happen,” Jackson said. “One person can’t move the needle, and that’s why this equity work so often feels doomed from the beginning.”

But Jackson said that Winn is using the resources at his disposal as a director of a major cancer center to “redistribute resources, build literacy and wealth in these communities in a way that might last.” Jackson said that helps Winn build a coalition across sectors like medicine, politics, or nonprofit that, together, can start to effect change.

That, Jackson said, goes beyond trust. “Winn has certainly accrued lots of trust, but his goal is clearly empowerment,” he said. “When you empower communities, it means they can interact with an institution on their own terms. Then you don’t have to worry about trust.” In the long run, he said, scientists would be “working with true partners.”

The work is already paying off for some of Massey Cancer Center’s researchers. Arnethea Sutton, a postdoc in cancer prevention and disparities research at Massey, said she used to struggle to recruit Black women to her studies. Even some of the people she’d known all her life, growing up as a Black woman in Virginia, or went to church with refused to participate.

“But recently, I really have not experienced too much of that,” she said. “And I think it’s had to do with my training.”

VCU’s Sheppard and Winn are both mentors to Sutton. She said they taught her how to engage and communicate with the Black community as a scientist, and the value of community partnerships. In many of the recent research studies Sheppard and Sutton have conducted, over 30% of participants were Black. In some of these studies, Sheppard, Sutton, and other VCU researchers were able to study ways to improve sample collection for research among Black women, cardiovascular disparities in cancer survivors, and how living in a disadvantaged neighborhood might affect cancer outcomes.

Winn doesn’t expect to see all the results he wants right away. He knows the changes he’s chasing will take time, and maybe not all the structures and systems he wants to reform will alter – or maybe not in his lifetime. “But it’s like the walls of Jericho,” Winn said. “They come tumbling down because you spin around the 10th time, 20th, or the 30th time. You have to be consistent in understanding your North Star. And this is my North Star.”

High tech, high touch isn’t a one-and-done approach, he explained. It’s showing up and banging on the walls over and over again. Slowly, he said, the data will come in, the science will improve, and the grants will flow. When others see that, Winn said, he hopes it’ll make more cancer centers and academic medical institutions follow suit.

“Maybe others would understand that it’s not enough just to come up with a great idea and then contract people to go out and get data from you from the neighborhoods,” Winn said. “Damn it, roll up your sleeves and get up in there. Go to a church. Go to an event. It won’t kill you.”

He’ll be out there, Winn said. Every weekend, every month, every year, he said, until the barriers between his people and his science are broken.

TRIALS AND TRUST: This series, on health equity and diversity in clinical trials and cancer research, was supported by the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2022 Impact Fund for Reporting on Health Equity and Health Systems. Part one examined how a breast cancer trial started attracting the Black participants it needed.

Next: How care navigators can help patients from marginalized backgrounds access better care and clinical trials.

[This article was originally published by STAT.]