When a killing near school hits home: Monyae’s story

Sonali Kohli worked on this project while participating in the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism's 2018 California Fellowship.

Other stories in this series include:

What it’s like to go to school when dozens have been killed nearby

Resources for students and families affected by violence near schools

How should journalists write about killings near schools? The students weigh in

Aaliyah attends PE class at Washington Prep High School in Los Angeles.

(Photo Credit: Marcus Yam/Los Angeles Times)

Brigitte Green hasn’t entered her son’s bedroom since she replaced his doorknob with a lock.

That was the day she returned home from the hospital without him.

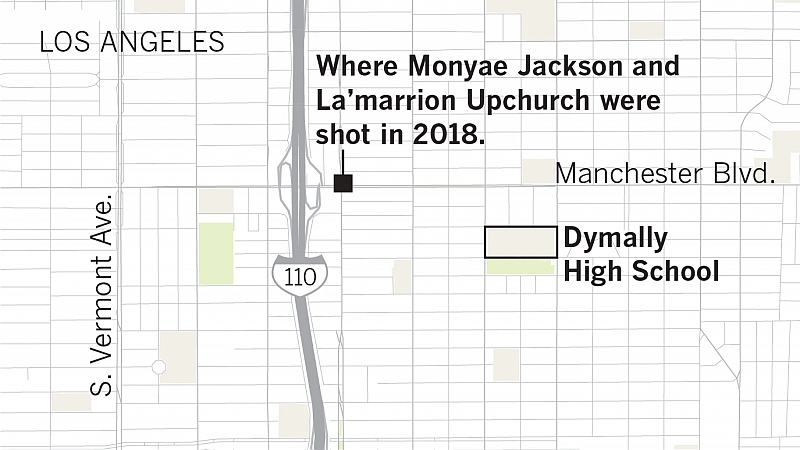

Her son, Monyae Ikeyli Jackson, was 15. As he and three friends walked from a party early on Mother’s Day last year, they were gunned down. Two survived. Monyae and La’marrion Upchurch, also 15, were killed.

The deaths shook local schools and left friends shattered. They left Green grieving, while she tries to keep the rest of her family going.

Sources: Mapzen, OpenStreetMap

Monyae was the fifth of six children. The youngest, Aaliyah, was 14 when he died.

She is a cheerleader at Washington Prep High School who on an application for a girls leadership program described herself as “outspoken, dedicated and loves to learn new things.” The 10th-grader is enrolled in an Advanced Placement world history class and honors English and gets mostly good grades. She missed some school when Monyae was killed, but otherwise has maintained almost perfect attendance.

Green doesn’t believe “in absences or tardies,” she said, and the dedication to schooling is on display at her home. At least a dozen perfect attendance trophies are clustered atop a chest of drawers in her bedroom — brought home by her children and Da’Codest Jester, the 12 year-old grandson she cares for.

“I’m very involved in their school … because I want them to be productive young men and young women,” she said. “I want them to get out in the world and not be afraid or ashamed to ask questions, and try to help correct the world.

Since her son’s death, Green keeps busy.

There are two children to shuttle — to two different schools, then to therapy for Aaliyah after cheer practice, and to football practice for Da’Codest. Green manages the logistics but hasn’t come to terms with her son’s death. The shock of it, the grief, overwhelms her in moments.

She and her family have relied on the wider community for support.

Tyrice Cagle, a pastor and youth intervention worker with the organization Chapter Two, had known Monyae from Hawkins High, where he greets students each morning as part of a safe passage program. Cagle reached out to the family, helped enroll Aaliyah in mentoring with Chapter Two, and helped Green navigate initial conversations with police.

“We already make a relationship with them before a tragedy happens,” Cagle said. “That’s the plan.”

Monyae was a football player. Teammates called him “Yoda,” because he was small, but quick and powerful. A variation of the nickname is tattooed on his mother’s neck. After his uncle died, Da’Codest decided he wanted to start playing football. Ronald White, who coaches the Compton Seahawks peewee team, helped drive him to and from practices and to games. Without that, it would be nearly impossible for him to play.

Da’Codest Jester listens to his grandmother Brigitte Green talk about Monyae, at home in Los Angeles. (Photo Credit: Marcus Yam/Los Angeles Times)

“I didn’t know that coach from a bowl of soup,” Green said. “But he heard about my son, and Cody said he wanted to play.”

While Da’Codest turned to football, Aaliyah has learned to cheer.

After her brother’s death, Aaliyah received a text from Charlé Johnson, Washington Prep’s cheer coach.

The week before, Aaliyah had tried out for the team. Those who made it were supposed to learn the news with balloons and personalized notes at school. Once Johnson heard that Monyae had died, she changed the plan for Aaliyah. She texted the freshman, sending her condolences and writing, “Although it may not change the hurt or pain you feel right now, but CONGRATSSS!! You made the CHEER SQUAD!!”

Green remembers hearing Aaliyah squeal, a brief moment of excitement in an otherwise hopeless time.

Johnson adjusted the schedule to give Aaliyah time to grieve, postponing cheer camp weeks later than usual.

During practice, if team members notice that Aaliyah seems down, they’ll try to pull her back in — ask how she’s doing, ask her to teach them a move or cheer, Johnson said.

“Aaliyah overall is a very silly, goofy, energetic type of young lady,” she said. “So it doesn’t take a lot to notice when she’s having a bad day.”

The hope, Johnson said, is that cheer offers Aaliyah a place to feel safe, happy and supported.

The school tries to provide other safe spaces such as the Margaret’s Place classroom, set aside for students who have experienced trauma, said the school’s principal, Dechele Byrd, who is also an alumna.

“[I’ve] lost friends that were killed when I was in school, so I can relate. Not necessarily siblings or any family members, but definitely know what that feels like to lose a friend or a loved one to some type of violence.”

Aaliyah recognizes the importance of having adults to talk to — she wants to be a therapist herself, she said.

“Some people have, like, emotional problems and they don’t really like to speak about it, so I want to be the person that they open up to,” she said.

But her mood sometimes swings.

“It’s a big difference from when she cheering and when she home,” Green said.

They still have their silly moments, and Green tries to laugh with her daughter as much as possible. But since Monyae’s death, Aaliyah has been quieter at home, sometimes leaving a room when others enter.

On top of grief, she had to contend with confusion over her brother’s death. It “makes me angry, and wonder” what happened to Monyae that night, Aaliyah said in June.

Police initially arrested only one person, but now three people have been charged in connection with the shooting.

Green, along with the parents of two boys who were with Monyae when he was killed, filed a federal lawsuit against the Los Angeles Police Department, accusing officers of violating their sons’ civil rights by restraining them at the scene when they were victims of a shooting.

The lawsuit alleges that Monyae’s death was due in part to a delay in medical attention because of how police treated him. The LAPD declined to comment on the lawsuit.

Monyae’s 16th birthday would have been in July. On that day, family and friends gathered at his grave site, still so fresh that there wasn’t a plaque, to celebrate his life. Green made food and picked up decorations, including a life-sized standing poster with Monyae’s photo. An hour in, Green was sitting by that poster sobbing, her dead son’s name newly inked onto her neck, as family members held her.

Brigitte Green is consoled at the burial site for her son, Monyae. (Photo Credit: Marcus Yam/Los Angeles Time)

Aaliyah honored her brother in her own way, playing his favorite songs and dancing, or talking to the friends she and her brother had shared.

On rare occasions, Green said, her daughter seems to snap. One day during late summer, Green saw that Aaliyah had pulled all the clothes out of a drawer and sprayed them with her water bottle. Green held her daughter.

“Because she’s a child, they take it in a different kind of way,” Green said. “A total different kind of way to where I didn’t understand that.”

But what Green did understand is that her daughter was in shock and hurting. She understood the loss they shared.

“I cried and I held her, and I told her it’s gonna be OK,” Green said.

She sometimes thinks that she and Aaliyah haven’t fully accepted the loss.

“I know I’m trying to stay strong and it’s, like, my poor baby trying to stay strong like me,” Green said, sitting on her couch on a Friday afternoon in the fall.

A little later, Green looked at the front door, as she often does, willing her son to walk through the living room and into his room like he used to.

[This story was originally published by the Los Angeles Times.]