Why it's so hard for kids in crisis to access the mental health care they need in Santa Clara County

This story was originally published in Mountain View Voice with support from the 2022 California Fellowship.

Brian plays on his electric keyboard while working on a song in his music studio in his Palo Alto home on Aug. 22, 2022.

Photo by Magali Gauthier.

When 14-year-old Brian got home to Palo Alto from a 5-week residential treatment program for depression earlier this year, there was one space that he couldn’t wait to be in again.

Stationed at the end of a narrow hallway, the dimly lit room glows from soft blue LED light strands framing the walls. A Beatles poster hangs above his modest setup: a record player, an electric keyboard, a studio mic. The indelible faces of John, Paul, George and Ringo command the space.

Brian’s studio is his sanctuary when he’s home. He’s been collecting vinyl since his 12th birthday and keeps his records in alphabetical order by artist, from Animal Collective to Wu-Tang Clan.

Before long, he started making his own music.

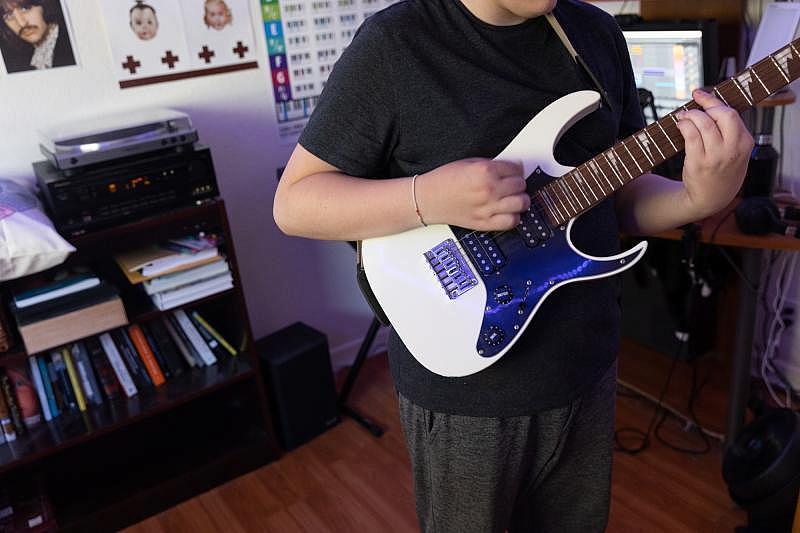

“It’s been really awesome to have as a coping skill and a tool for me to just express myself and get my ideas out there,” said Brian, a pseudonym the Voice agreed to use to protect his privacy. “But also just to be able to show people how important music is for a lot of people, especially teens with mental health issues.”

Brian searches for part of a song by The Arthur Lyman Group that he has sampled in his own music in his studio in his Palo Alto home on Aug. 22, 2022. Photo by Magali Gauthier.

Music has been there for Brian when mental health resources weren’t. He’s battled depression and suicidal behavior since he was 10 years old. When he first started considering suicide, his family had to wait weeks just to get him an appointment with a psychiatrist. When his depression relapsed during the pandemic, Brian waited months to begin a treatment program.

“I don’t want to say that music saved my life,” Brian said. “But it definitely played a big role in keeping me here.”

Mental health care provider shortages are rampant across the United States, and are only worsening. A 2016 report from the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) projects a deficit of more than 10,000 psychiatrists, mental health counselors and school-based counselors and psychologists by the year 2025. Today, the number of additional providers needed to meet the demand has already swelled to nearly 7,800, according to HRSA data.

That crisis is going to be especially felt for youth and adolescents like Brian. People in this age group already faced a slew of unique mental health challenges, even before the COVID-19 pandemic cut off their access to crucial support systems at school. With a dearth of youth-specialized private practitioners who accept insurance, Bay Area families often struggle to find adequate help for their kids.

“When we go out and talk with folks in our research, we hear especially acute challenges with child and adolescent psychiatrists,” said Dr. Janet Coffman, co-associate director for policy programs at the University of California, San Francisco Institute for Health Policy Studies. “More so than others.”

When demand exceeds supply

One reason for the drought of youth-specialized providers, according to Coffman, is a lack of incentives.

A medical student might be financially motivated to specialize in cardiology, for example, because the extra years of training pay off with a higher income. The same isn’t true for mental health doctors. After going to medical school and doing a four year residency to become a general psychiatrist, specializing in child and adolescent psychiatry requires another one to two years of training.

“And at the end of the day, you won’t get a financial return on your investment,” Coffman said. “We don’t pay child psychiatrists substantially more than general psychiatrists” – and by “we,” she means the insurance companies that set reimbursement rates.

Brian has witnessed this severe lack of child psychiatrists firsthand. When he first experienced suicidal thoughts at age 10, he and his mother, Katherine, quickly learned just how hard it is to find help for youth in crisis in the Bay Area. The Voice agreed to use a pseudonym to protect Katherine’s anonymity.

“I started calling around to try to find a psychiatrist,” Katherine remembers. “I knew that I had to get him on some sort of antidepressant to help get him out of the deep hole that he was in so that he could access therapy.”

Many of the psychiatrists Katherine called were not accepting new patients. If they did have any availability, Brian was looking at a multi-month waitlist before he could be seen.

Brian works on a song in his music studio in his Palo Alto home on Aug. 22, 2022. Photo by Magali Gauthier.

Katherine didn’t know what to do. She had a child who was in imminent physical danger, yet everywhere she called, Brian’s situation was met with a lack of urgency, as if he just had a toothache or was stressed with schoolwork. Brian’s pediatrician advised Katherine to take him to the emergency room.

“My hope at the time was that we would go to the ER, we would leave with a prescription in hand and then a very quick referral to some psychiatrist at Stanford who could help him,” Katherine said. “That definitely did not happen.”

The emergency room chose not to admit Brian, and it took about six weeks before he got to see a psychiatrist. And that was only because Katherine had the help of a psychiatrist who pulled some strings and got Brian an appointment with a provider in their insurance network – “miraculously,” she said.

Saying it’s a miracle that Katherine was able to find a provider who accepted the family's insurance isn’t much of an exaggeration: Experts say psychiatrists and therapists are among the least likely of all types of health care providers to accept insurance. And in the Bay Area, where practitioners can easily charge more than what insurance companies will reimburse, providers are opting for out-of-pocket payment models at alarming rates, said Dr. Philip Cawkwell, a child and adolescent psychiatrist with Bay Area Clinical Associates (BACA).

“Every psychiatrist you lose to private practice is just another that can’t see average folks,” he said. “It’s a tough reality of where we live.

When Brian finally saw a psychiatrist and got on medication, he initially became stable. He saw a therapist regularly and was able to manage his depression for a couple years.

“Then in 2020, we’d been in COVID for about six months,” Katherine said. “We’d been at home, pretty isolated, and he started feeling depressed again.”

A pandemic impact

A chronic lack of supply made the search for adolescent psychiatric help taxing in a pre-pandemic world, and the surge in demand for services during the pandemic only exacerbated the shortage, said Coffman at UCSF.

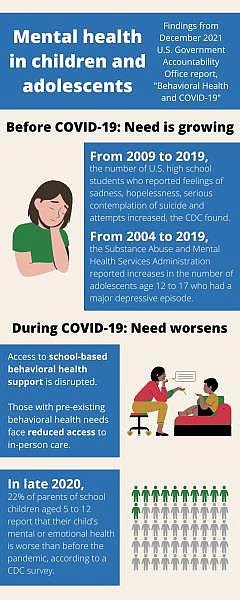

Graphic by Malea Martin. Findings courtesy U.S. Government Accountability Office.

“If we look at data for the need and demand for mental health services pre-COVID, we were already seeing an increase in prevalence of things like depression and anxiety among children and adolescents,” she said. “Then during COVID it kind of shot up. So there was a general slope, and then there was a spike.”

Brian said the best word to describe his mental health journey so far is “rollercoaster” – a constant undulation of highs and lows. But COVID, he said, felt like a nosedive.

“So many kids needed help, and they just weren’t able to get it,” he said. “I’m sure a lot of people have died because of this situation.”

In late 2020, Brian made a plan to end his own life. Though he didn’t go through with it, when Katherine learned of her son’s aborted suicide plan, she knew he needed urgent care to become stable again. She took him back to the emergency room, and this time he was admitted. But he had to wait more than 24 hours just to get a bed.

“I have come to find out that’s actually quick in the emergency room to find a bed, because at this point we were in COVID and beds were even more scarce,” Katherine said.

After Brian was released, his doctors told his mom, “Find an IOP.” Experts say IOPs, or intensive outpatient programs, are the gold standard for youth experiencing mental health struggles.

“It means you’re meeting four days a week for three hours every day for eight weeks,” said Cawkwell. “That’s a lot more intensive and that’s a lot more services than if you’re just needing a 45-minute appointment every few weeks.”

But there are few IOPs accepting patients in the Bay Area, and even fewer that accept insurance, Cawkwell said. Plus, IOPs are specialized, so not every mental health condition is the right fit for every IOP.

A space where group therapy is held at Bay Area Clinical Associates in San Jose on Sept. 6, 2022. Photo by Magali Gauthier.

A new program that Cawkwell is spearheading through BACA, for instance, will be the only IOP for youth experiencing psychosis that accepts major insurance in the Bay Area, he said. The only other comparable program for this specific mental health condition in California that he is aware of is in Los Angeles.

“It’s actually better in California to not have (private) insurance” when it comes to treating severe mental health issues in youth, Cawkwell said. “It’s better to have Medi-Cal, because all of these programs are county-run.”

Santa Clara County’s Behavioral Health Department offers dedicated programs to youth with Medi-Cal, from early intervention to residential services, said Zelia Faria Costa, director of the department’s children, youth and family system of care.

“They’re really excellent programs,” Cawkwell said. “But for a lot of our teenagers and young adults who have their parents’ (private) insurance, there isn’t a great level of care for them.”

Being met with waitlist after waitlist was “demoralizing,” Brian said.

“It’s basically the system’s way of saying, ‘Your problems aren’t important because you’re not sick.’”

Prohibitive costs

This nationwide issue is only made more acute in a place like the Bay Area.

“You have a lot of high-income earners,” Cawkwell said. “So you have a lot of psychiatrists who just don’t take insurance because they can charge whatever they want in private practice.”

The issue comes back to how much insurance companies are willing to reimburse providers.

Dr. Philip Cawkwell, a child, adolescent and adult psychiatrist, in his office at Bay Area Clinical Associates in San Jose on Sept. 6, 2022. Photo by Magali Gauthier.

“If you’re practicing in Nebraska, you can’t do a private practice where you set your rates to be triple what insurers are paying,” Cawkwell said, because there aren’t nearly as many people there who can afford that.

“But you can do that in the Bay Area,” he continued. “A decent number of psychiatrists end up doing that because that market is there.”

What results is a group often dubbed the missing middle: the folks who earn too much to qualify for Medi-Cal and the county-run resources that come with it, but not so much that they can afford to pay out of pocket when private providers don’t accept their insurance.

This pre-pandemic reality combined with the unprecedented need brought on by COVID-19 led the American Academy of Pediatrics, American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Children’s Hospital Association to jointly declare a national emergency in youth mental health in October 2021.

But the pandemic was by no means the first time that youth mental health reached crisis levels in Silicon Valley. Teen suicide clusters in Palo Alto made national news headlines multiple times in the last decade and prompted an investigation by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in 2016.

“Academics are life here,” said Amrita Vu, lead site therapist at Los Gatos High School who was previously the lead therapist at Los Altos High School. “There is this underlying academic pressure, whether it be from families, whether it be from peers – this need to compete in order to excel. And that definitely affects our students’ mental health.”

Reaching the underserved

Low-income students face a lot of barriers to accessing mental health care. They may not be able to afford it, don’t feel comfortable bringing it up with their families, or just don’t know it’s an option.

“Who else is going to serve our underserved population?” said Vu. “That’s why I think it’s really cool that our schools are providing free services.”

Data visualization by Malea Martin. Data courtesy ACLU.

School-based mental health services were there for one Mountain View family when they needed it the most. A single father told the Voice in an interview that if his teenage daughter hadn’t received therapy from Los Altos High School, he’s not sure if she would have gotten the help she needed at all. He asked the Voice not to reveal his name to protect his family’s anonymity.

“After my divorce I was taking care of my two daughters,” he told the Voice. “We struggled a lot for three and a half years. We were homeless for two months.”

Shortly after the pandemic began, the father was the victim of a robbery attack, during which he was severely injured. Then in September 2021, the family lost their apartment to a fire.

“It affected my kids a lot, because it was a shock,” he said. “We were again living in hotels and stuff.”

He knew that his eldest daughter needed professional help, “but I couldn’t find the words to erase the bad things we had been through,” he said. “It wasn’t enough. ... I was looking for a therapist for her, but without money it’s just so hard.”

He received a call from his daughter’s school and learned that she was self-harming. She was connected with a therapist through LAHS whom she started to see regularly.

“She did very well, they did a really good job,” he said. “She feels very confident now. She’s feeling OK to get back to school without struggling or having nightmares about all the stuff that we lost.”

If his daughter hadn’t had access to a therapist at school, he wonders what might have happened.

“I imagine the worst,” he said. “Because she was struggling until she got hurt. They helped her immediately.”

Amrita Vu, the site lead therapist, inside the Wellness Center at Los Gatos High School in Los Gatos on Aug. 25, 2022. Photo by Magali Gauthier.

Meeting the need

According to a 2019 ACLU report, up to 80% of youth don’t receive the mental health services they need in their community because supply and services are inadequate.

“Of those who do receive assistance, 70% to 80% of youth receive their mental health services in their schools,” the report found. “Students are 21 times more likely to visit school-based health centers for mental health than community mental health centers.”

During the pandemic, those vital resources were interrupted. Los Gatos High School's Vu, like countless other school-based therapists, was forced to go virtual.

“It was difficult,” she remembers, “to go from being hands-on, doing a lot of my assessments based off of body language, to only literally seeing like a mugshot of the student. I saw a lot of social isolation.”

Julie Chen, now a rising senior at Los Gatos High School, was still new to the Bay Area in 2020. Before moving to Silicon Valley from the Chicago suburbs just before her freshman year of high school, Chen hadn’t given much thought to mental health.

“I feel like everything was much more simple over there,” she said. “It wasn’t until moving here that I really started realizing that everything here is so fast-paced and super competitive, even among my closest friends. There’s always going to be some tension whenever talking about school or classes or anything like that.”

Senior Julie Chen at the Wellness Center at Los Gatos High School in Los Gatos on Aug. 25, 2022. Photo by Magali Gauthier.

When the pandemic hit during her freshman year, at first, Chen said she felt like she could finally catch a breath. But as summer rolled around, the isolation began to creep in. That summer, she ended up joining Cats to Cats, a Los Gatos High School peer-to-peer program.

“Without Cats to Cats I didn’t know who else I could reach out to,” Chen said. “We have therapists at school who are incredible people, but it’s just hard for me, and I’m sure a lot of other people, to just immediately reach out to adult figures who I’m not super familiar with.”

When Chen and her peers got back to campus in August 2021, they had a new resource waiting for them: the Wellness Center. Vu and her colleagues spearheaded this designated mental health space – filled with comfy couches, twinkly lights and stress-relieving activities – for students to access when they need someone to talk to or a moment away from the pressure.

“The Wellness Center was definitely like a second home for me,” Chen said. “I just felt really safe in that space. Amrita (Vu) and our Wellness Center coordinator (Mariana Cozzella), both of them I’ve grown a connection with that feels like a small Wellness Center family. I’ve never felt so comfortable with any adult figure at school before.”

Amrita Vu, the site lead therapist, looks up at senior Julie Chen while they play a game in the Wellness Center at Los Gatos High School in Los Gatos on Aug. 25, 2022. Photo by Magali Gauthier.

Due to the severe shortage of mental health resources for young people, school-based mental health resources and providers are often the first touchpoint that kids have when they’re struggling, according to the ACLU report.

“Research has shown that school-based mental health providers improve school climate and other positive outcomes for students,” the report said.

Schools that employ therapists and offer mental health resources also see better attendance rates, lower suspension and expulsion rates, improved academic achievement and higher graduation rates, the report found. But public schools that do employ mental health professionals are almost always understaffed.

Professional standards recommend at least one counselor for every 250 students, the report said. But in California, 96% of students are in schools where counselor caseloads do not meet this recommendation. California has the third highest ratio in the country, at 682 students per counselor on average, according to the report. Santa Clara County’s ratio was even worse than the state average at 746 counselors per student in 2019, according to data from the Population Reference Bureau.

Data visualization by Malea Martin. Data courtesy ACLU and Population Reference Bureau.

Some state lawmakers are trying to bridge that gap through legislation. Senate Bill 1229, dubbed the Mental Health Workforce Grant Program, passed unanimously in the California Senate in May. If signed into law, the legislation would offer up to $25,000 in grants for students pursuing careers in school counseling. The law aims to bring 10,000 new mental health providers to young people in the state.

But even with solutions like these coming down the pipeline, there will always be young people who need a higher level of care than a school setting can possibly provide. People like Brian.

The cost of high-level care

When Brian’s depression and suicidal behavior resurfaced in late 2020, Katherine was roadblocked by monthslong waitlists as she began the search for an intensive outpatient program that would accept her son. It wasn’t until March 2021 that Brian was able to start a program, which was virtual due to COVID-19.

“It was helpful in a way, because I’m a single mom and I work and it would have been hard to get him there and back,” Katherine said. “But because it was virtual, it just doesn’t work.”

The program providers told Katherine that her son needed a higher level of care. She began her search for a residential treatment center, but couldn’t find any Bay Area options that were accepting patients and would take her insurance.

Brian pets his cat Yin Yang while others scurry about his guitars in his music studio in his Palo Alto home on Aug. 22, 2022. Photo by Magali Gauthier.

“I have United health care and, I have come to find out, United Behavioral Health is like one of the worst in terms of paying for mental health claims,” Katherine said.

The federal Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act requires insurance coverage for mental health conditions to be no more restrictive than insurance coverage for other medical conditions. But as the US Government Accountability Office (GAO) identified in a 2021 report, “even before the pandemic, long-standing questions were raised about whether coverage or claims for behavioral health services are denied or delayed at higher rates than those for other health services.”

In a 2019 class action lawsuit, a federal district court ruled that United Behavioral Health, Katherine’s insurance provider, “had adopted behavioral health service coverage guidelines inconsistent with the standard of care and had improperly denied the plaintiffs benefits for such services,” GAO said in its report.

At the time, United Behavioral Health was ordered to reprocess more than 67,000 coverage claims for 50,000 patients, half of which were for children, according to The Kennedy Forum, a legal organization that advocates for the full implementation of the Mental Health Parity Act. But in March 2022, the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals reversed the district court’s order on the basis that it’s “not unreasonable” for insurers’ coverage to be inconsistent with accepted standards of mental health care.

“The current ruling will embolden insurers to make decisions out of step with clinical standards,” The Kennedy Center wrote of the March decision. “The ripple effects of this case will greatly impact society.”

When asked to comment on the case, United Behavioral Health said in an emailed statement that over the past several years, the company has taken “concrete steps to improve access to quality care by enhancing coverage through clinician-developed evidence-based guidelines, expanding our network of care providers, and providing new ways for people to quickly access care through telehealth and other digital platforms.”

For Katherine, it got to the point where she had to start looking out of state to find care for Brian. She eventually found an acute inpatient program in Utah that could provide what he needed.

“He was there for a month, but I had to fight with insurance literally every day to continue to get coverage,” Katherine said. “To get him into this hospital in Utah, I had to pay them a deposit for the first two weeks of treatment, which was $20,000 – just for them to admit him. That was knowing that this facility is in network with my insurance, they still required a $20,000 deposit.”

A brighter future

While increasing the stock of behavioral health providers that accept insurance would help youth like Brian get the care they need closer to home, “even if every single psychiatrist took insurance, there would still be a shortage,” psychiatrist Cawkwell said. “There just aren’t enough.”

There are some nationwide efforts to incentivize more providers to serve in nonprofit organizations or in underserved communities, such as the Public Service Loan Forgiveness program and loan repayment awards offered through the National Health Service Corps. But there’s not much, if any, federal effort to incentivize more providers to specialize in youth and adolescent behavioral health.

“People who are willing to work with children and adolescents often have a strong interest in that area and specialized training, so you can’t just recruit adult therapists or other populations to fill in,” Cawkwell said.

And in Santa Clara County, it’s not just the providers that are lacking, but also the facilities. County Supervisor Joe Simitian, whose district includes Mountain View and Palo Alto, said he vividly remembers the day in 2014 when he learned from a constituent at a holiday party that there was not a single inpatient psychiatric bed for children and adolescents within the county.

“I said, ‘Surely, that can’t be right,’ and she said, ‘I assure you it is,’” Simitian remembers. “I went back to the office and discovered that was absolutely the case.”

Simitian was determined to change this, and in 2017, the Board of Supervisors directed staff to build an adolescent inpatient psychiatric unit at the Santa Clara Valley Medical Center in San Jose.

“Creating 30-plus beds in Santa Clara County is no small thing,” Simitian said. “It has been a challenge. We’ve had a few false starts. But, we’re going to break ground on that in the coming months.”

What’s especially significant about the new unit is it will accommodate patients regardless of their insurance type, Simitian said.

“If you are a well-insured family, your kid can make it there. If you are without resources or you’re Medi-Cal, your kid will have a place there. If you are out of pocket, your kid will have a place there,” Simitian said. “It’s designed to serve that full range, it is not designed to be limited to a safety-net population.”

On the less tangible side of the issue, what makes Cawkwell hopeful is the decrease in mental health stigma that he’s witnessed in the past few decades – especially among youth.

“I hope that it means some of these teenagers will want to grow up to be psychotherapists or psychiatrists,” Cawkwell said.

Brian’s not sure what his future holds yet. Like any teenager, he’s still getting to know his place in the world. When he spoke to the Voice, he had just finished his second residential treatment program and was getting ready to start his freshman year of high school.

Brian plays the guitar in his music studio in his Palo Alto home on Aug. 22, 2022. Photo by Magali Gauthier.

“In the 35 days that I was there, I think I’ve learned a lot,” Brian said. “These skills work. They make such a huge difference.”

As helpful as the program was, Brian believes no one should have to wait as long as he did to receive care.

“The fact that it’s so difficult for a lot of kids to get the mental health treatment that they needed after COVID shows that the system and the government and the health care situation in this country, they see physical health as leaps more important than mental health,” he said. “Mental health should be just as important as physical health.”

More than anything, Brian said, he just wants to feel safe.

“Recovery takes time,” he said. “I guess I’m working toward not being scared of being alive.”

Any person who is feeling depressed, troubled or suicidal can call 1-800-784-2433 to speak with a crisis counselor. People in Santa Clara County can call 1-855-278-4204. Spanish speakers can call 1-888-628-9454. People can reach trained counselors at Crisis Text Line by texting 741741.