Will losing your home kill you?

This is part three of a series of articles examining the relationship between housing loss and death in San Francisco.

Part One: Looking for death on the streets. And finding it.

Part Two: Gunpowder on the street

Part Four: Hidden in plain sight: dying and homelessness

Part Five: Be selfish, give a gift to a homeless person

Part Six: Living and dying in the Tenderloin: substance abuse and Nate

Part Seven: Starving in the Financial District: Ken and food insecurity

Part Eight: The Sixth and Mission death corridor: assaults, brain trauma and homicide

Part Nine: Steve, Tori and the Western Addition: Raising children without a stable bed

Part Ten: Mary, Melodie and the Mission district: Women brutalized on our sidewalks

If you work in a homeless clinic, every so often you're going to see a Mike. He's easy to spot in the waiting room because his clothes are too business-y and nice. But there is always some detail that gives him away. This time, it's his hair that's mashed up in back and he doesn't seem to know it. Three months ago he went through a divorce and lost his house to the IRS. For two months, he's been living out of his car, wheeling and dealing, trying to put something together, sponge-bathing in public toilets. He came in because he's recently lost his car, and then his phone, and you get the feeling he waited two hours to be seen mostly hoping you'll let him use a clinic phone to make a bunch of calls. He can't really say why he's here, his speech is pressured and he's only got a roll of blankets to keep him warm and he's vibrating with stress, his hoarse voice rising as he describes his life, how his back is killing him, how he can't sleep, and you notice that his hands are shaking.

It's difficult to listen to him, and you realize that part of the reason is because maybe, his story is a little too close to home.

Is it the lost home? Or the loser?

Even if the death rates among the homeless are higher, isn't it just because the people we're talking about are deeply flawed to begin with? You've probably heard people say that the only reason someone is homeless (especially those chronically homeless) is because they're not like you and me. Hey, you're no Scrooge, and neither are your colleagues and friends, but dinner conversations on this topic still sound uncomfortably similar to when Scrooge says, "I help to support the establishments I have mentioned - they cost enough and those who are badly off must go there," adding, "If they would rather die, they had better do it, and decrease the surplus population."

If it's any consolation, the Scrooge response is pretty common. In the November-December Harvard magazine, there is an interview with social psychologist Ann Cuddy, who studies perceptions of social groups. She describes the "contempt" quadrant, which is populated by the homeless, welfare recipients, poor people. "They're blamed for their misfortune," Cuddy says. "They are both neglected and, at times, become the targets of active harm." Deep-seated cognitive patterns may prepare the way for maltreatment. "There's an area of the brain, the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), that is necessary for social perception," she explains. Recent imaging research showed no activation of the mPFC in response to pictures of homeless people. Cuddy points out: "People are not even recognizing them as human."

The numbers argue otherwise. A study from New York found that the reasons for homelessness, even before the downturn of the economy, did not significantly differ between those people who were mentally ill (either defined broadly or narrowly), and those who had no diagnosis of mental illness at all. Insufficient income, job loss and lack of suitable housing were the same for all groups.

And like a rising tide, home loss seems to be inching closer to all of us. One in 10 Bay Area homeowners is projected to be more than 60 days delinquent on their mortgage, a number that has soared up from 1 in 100 in 2007. Those numbers may already have worsened, and they don't reflect the renters who've lost or are threatened with the loss of their homes, or the people who have begun to "couch surf" after being unable to find a job.

But is "homelessness" different from home loss? Institutions like the foster system, the prisons, and the lack of mental health resources are all acknowledged contributors to homelessness. But both academic studies and homeless people themselves often report that the reason for their homelessness is more mundane than you might expect, even in countries with comprehensive social safety nets - eviction, divorce, domestic violence and job loss. Here, the 2009 San Francisco survey showed that a good 57.7% of people on the street self-reported reasons that may be closer to our own lives than many of us expect: things such as landlord sold home/stopped renting/raised rent (3.4%), or eviction (5.3%), or lost home to foreclosure (1.3%). Reasons of divorce, separation, domestic violence, death in the family, illness and hospitalization all added up to 11.9%. And then there's lost job (25.2%).

So, listening to Mike, the uncomfortable thought emerges - if you were put out there on Sixth and Mission for three months, no money, no family, no friends, how well would you do? And how much would you change before it was over?

The process, or the person?

Mike goes on and on about how impossible it is to get a shelter bed, how many hours it takes to stand in line for a meal, how he hasn't slept in days, how three people beat him up and took his phone a couple of nights ago. He is pacing, crowding you in the tiny exam room. He can't believe there's no help, that there's nothing you can do for him and you edge toward the door, wondering if you should call security. Maybe he used to be a two or three glass-of-wine with dinner kind of guy, and now he's switched to a cheaper version of alcohol.

A study in Amsterdam showed that who gets evicted (as opposed to who gets to stay and work out their financial problems) may be increased by such factors as whether you're a single man, or have relationship difficulties, or medical problems, or "nuisance issues," like debts or addictions. Are some economically-fragile people more often pushed into homelessness purely because they're less appealing? If so, social isolation is not likely to improve on the street.

Watching even Mike, who kept a job for decades and maintained a marriage for years, you know, deep inside, that if something doesn't change, soon he too will have a shopping cart. It's all too easy to imagine him losing it and shouting at someone on the street. His faith in systems, and institutions, and his willingness to reach out have been almost completely destroyed. In only a few months, he's taken a tremendous hit to his psyche. And he's also taken an equal hit to his health.

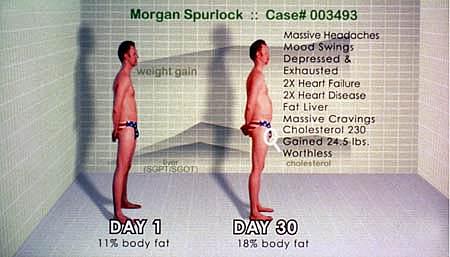

He tells you he's got a cough from inhaling clouds of diesel and all the damn cigarette smoke everywhere. He says with disgust that he's eating "pure crap." You realize he's become a living, breathing re-enactment of the movie SuperSize Me. But unlike Morgan Spurlock, Mike is taking the additional hit of constant mega-stress, unending physical strain, numerous mini-traumas, and days of sleep-deprivation. For the first time in his life his blood pressure is high and his face is a congested red. And the changes probably started months ago, when the process of losing everything began.

A New York study showed that the newly homeless are often quite ill with multiple medical problems. And with an estimated 60-75% of American bankruptcies attributable to medical costs, there is a disturbing chicken and egg aspect to the issue of poor health and home loss.

But you may wonder, isn't the health hit just from the poverty, though, instead of the threat of losing one's home? A Bay Area study found that people undergoing foreclosure were more likely to suffer from increased medical problems, and higher rates of stress. A Canadian study looking at over 15,000 people living both in shelters and also those "marginally housed" found extremely high rates of death - even when controlling for equivalent poverty. If you were an unstably housed 25 year old man - not homeless, just living with the constant threat of homelessness - you only had a 32% chance of making it to age 75 (the usual life expectancy). And just how are these people threatened with home loss dying? "For both sexes, the largest differences in mortality rates were for smoking related diseases, ischaemic heart disease, and respiratory diseases." In other words, what most of us would consider classic, often treatable, medical problems. There seems to be a measurable, definite toll on survival that is caused purely by the chronic threat of home loss.

Desperation, and distraction, may be affecting long-term health and behavior, even if you're young, even before a home is gone. One study showed that if you're young, and your housing is in jeopardy, you're more likely to have multiple sex partners. Even after other factors are controlled, people who use drugs and are "precariously housed" are more likely to have been infected with hepatitis C.

So if studies show that being threatened with losing your home increases your chances of dying and shortens your life, what can you do about it? If you're struggling with constant stress and home insecurity, here are some tips on how you can push back to buffer or reclaim your health. And if being threatened with home loss can affect your health, what happens once you've actually lost your home? Does losing your home take a year off your life? A decade? Or more?

*Names and dates are changed to protect confidentiality.