2017 National Fellows delve into the ethical quandaries that come up while reporting

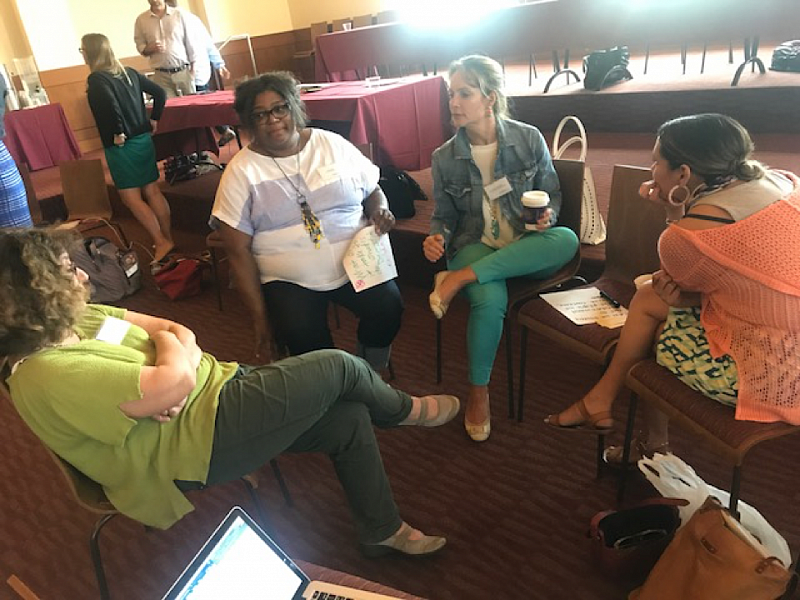

During the 2017 National Fellowship last week, we decided to venture into unchartered territory by getting a group of newly introduced journalists to sit in a circle and talk about their feelings.

Peggy Holman, executive director of the nonprofit Journalism That Matters, began our group session with these words: “I invite you to take a look at the people who are here with you. In many ways, these are your traveling companions, and among you is the passion, commitment, knowledge, skills, creativity, and compassion to make the connections that you need to take this work where you want it to go.”

With that in mind, Holman prompted our fellows to think of any questions or conversation topics they’d like to explore and then report back to the group. The topics of interest were wide-ranging: using data-driven material to tell compelling stories, gaining the trust of vulnerable populations, honoring objectivity while remaining ethically engaged, and the politics of solutions journalism.

Many Fellows joined a discussion on the challenge of remaining objective while remaining true to each reporter's personal ethical compass. Freelance writer Lily Dayton, whose fellowship project explores how foster care youth get caught up in sex trafficking, emphasized the importance of direct language when reporting on sensitive topics. “I’m really interested in presenting what’s going on — what are the holes in the system — but also being really clear in stating that these kids are victims,” Dayton said. “I want to write a piece that’s not used as advocacy, but opens up questions on the issue.”

Arizona Daily Star border reporter Perla Trevizo was interested in ways to capture a range of perspectives on an issue, rather than only polarized sides. “In the Southeast, as a Mexican-American reporting on immigration, I was always more scrutinized,” Trevizo said. “Immigrants assumed I was their friend, and the other side thinks I’m biased. But you run the risk of not necessarily representing the vast majority when you quote the extreme left and right. How do you maintain objectivity without just having to quote both sides?"

NBC News correspondent Tracie Potts took it a step further: “And to what extent do you give a fair voice to the uninformed opinion? For someone who has skin in the game, is that really lending to informed conversation?” She continued, “But who am I to say that they don’t have a voice? That’s always been a bit of a challenge to me.”

Dara Lind, an immigration and criminal justice writer for Vox.com, added, “If you repeat the myth rather than fact checking, people repeat the myth. But when you allow people to be the protagonists of their own story, and give them enough space to explain their own perspective, you allow readers to come to their own conclusions, which results in a more compelling narrative.”

Another group of fellows wrestled with the question of how close you can get to the community you’re reporting on — while remaining unbiased. Telemundo correspondent Cristina Londoño began the discussion by sharing how she makes sure to adhere to cultural norms when entering a community. “You definitely eat what they give you,” Londoño said. “You sit in that house, even if you have to sit in a room with roaches crawling all over if that’s where they are. In consumer-focused reporting, you have to be a lot more compassionate.” She continued: “I know if I’m interviewing a Hispanic family around breakfast time and there are kids in that family, I’m bringing them breakfast. That’s where you have to understand the community and understand that you’re asking them to make a sacrifice.”

In response, senior editor Karen Brown posed this question: “But is there a line you wouldn’t cross? Is that confusing to you sometimes? Being empathetic makes sense. Getting breakfast is a grey area … You don’t feel that it compromises your ability to cover that community? Your line may be much thinner than some.”

Tessa Duvall, a reporter at The Florida Times-Union, said that while reporting on juveniles in Jacksonville who face murder charges, one source asked if Duvall could connect them with a good attorney. “I wrote back that I can’t give legal advice, but what I can do is tell you that this is a chance to share your experiences,” Duvall said. “This is an opportunity to be heard and a lot of these people are not used to being heard.”

Potts distinguished between perspective and bias, and suggested the former is inevitable and even helpful:

“There are different types of journalism and I think we need to be very up front about who we’re covering, and what we’re doing. But we are individuals. I bring to the story my perspective: my perspective as a woman, as a mother, as many things. It helps inform the story and inform the questions. But the output needs to be unbiased. I’m here to tell you the facts. Perspective and bias are two different things, and perspective can help going in to a story. The perspective you and I have can be very different, and that can help the story. But it needs to be objective and unbiased on the output end.”