Adverse childhood experiences don’t tell the whole story. What about the positive experiences?

(Photo by Aimee Dilger/SOPA Images/LightRocket via Getty Images)

Nearly two-thirds of U.S. adults can recall at least one adverse experience as a child, such as abuse or mental illness in the home. Researchers have shown that more adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) are associated with poorer health in adulthood.

But adversity is only part of the story, according to Angela Narayan, an associate professor of clinical child psychology at the University of Denver.

“What about resilience? What about the people who experience ACEs and don’t have negative health outcomes?...What about positive experiences?” asked Narayan while addressing journalists at the Center for Health Journalism’s 2024 National Fellowship last week.

She defined resilience not as a trait but rather the process of adapting and doing well, despite risks to one’s healthy development. Having a stable and committed relationship with a caring adult is an important factor for a child to develop resilience, according to the Harvard University Center for the Developing Child.

Narayan’s research has expanded the focus to also include the impact of benevolent childhood experiences or BCEs, which may help buffer against ACEs. Benevolent childhood experiences can be things, such as having a good friend or liking school.

Narayan said the BCEs questionnaire that she developed has 10-items that query about positive experiences, such as having a safe caregiver, friends or a supportive teacher. The survey, which strives to be culturally sensitive, has been used in multiple countries and in populations with wide range of demographics, such as different ethnicities, socioeconomic status or housing security. Almost universally, about 90% of adults surveyed can identify at least one BCE.

The BCEs survey of positive events stands in contrast to the emphasis on negative experiences in the ACEs survey.

The original ACEs study looked at 10 experiences, such as abuse, domestic violence or parental divorce, that occurred before age 18, as reported in surveys of more than 17,000 Kaiser adult patients. The researchers found that the more ACEs reported by a person, the higher their risk for poor health outcomes as adults, such as mental illness and heart disease, and even early death.

Narayan said the 1998 study’s findings were “groundbreaking,” noting that these forms of adversity were common (more than 60% of adults having at least one) regardless of race or ethnicity, though they were more frequent in marginalized communities.

“I think the ACEs checklist is a great way to understand peoples’ lived experiences as a group, like for research participants … (but) not for giving each individual their health outcomes,” she said.

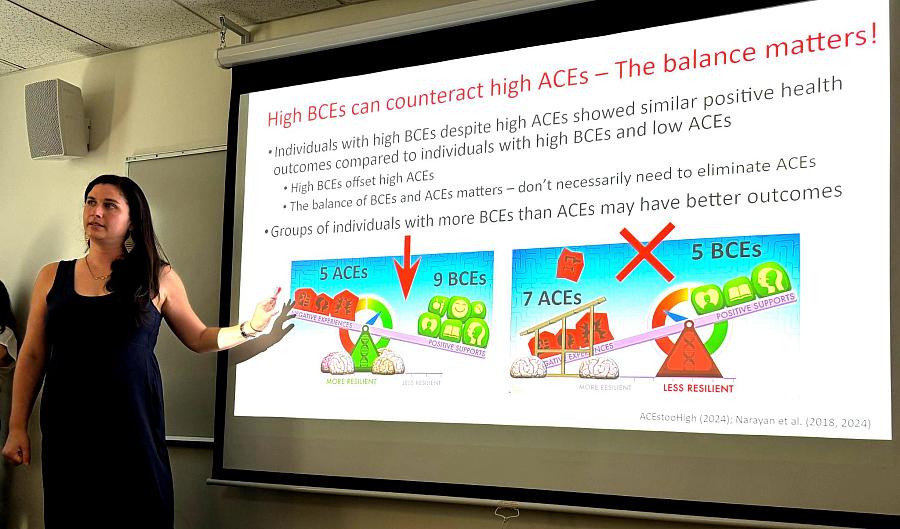

Narayan’s biggest criticism of the ACEs framework is that it doesn’t account for positive experiences. In her research, as well as others, groups with higher numbers of BCEs appear to suffer fewer of the negative effects associated with ACEs, such as symptoms of psychological distress or post-traumatic stress disorder. For example, study participants with nine or more BCEs — along with five or more ACEs — seemed to function as well on average as those with only one or two ACEs.

Another limitation: Each of the 10 adverse experiences is treated as equivalent in weight, and they may not be. For example, a divorce for a child living in a violent household may be a benefit, not a detriment. Also, the checklist is not developmentally informed; experiencing adversity at young age is different than as a teen.

Narayan also pointed out that many items are missing from the original 10-item ACES survey checklist, such as living in a marginalized or oppressed community, peer-victimization, and intergenerational racism, among others. In recent years, researchers have added some of these items to ACEs inventories.

The survey also relies on self-reported answers. Narayan likes that people can report their own experiences, though they may have memory flaws. She noted self-reporting is in contrast to the “gold standard” for psychology research, which assumes that adults’ recall of childhood events is not always accurate.

Angela Narayan, an associate professor of clinical child psychology at the University of Denver, speaks to journalists about her research on childhood adversity at the USC Center for Health Journalism's 2024 National Fellowship in Los Angeles on June 27.

(Photo by ChrisAnna Mink/CHJ)

A growing number of pediatric and mental health providers have instituted screening for ACEs in children in recent years. In California, the Office of the Surgeon General recommends using a pediatric version of the ACEs survey.

“I don’t love the ACEs framework. I think it’s mostly harmful. I think BCEs can make it helpful, if done in the right way,” Narayan said.

“It’s hard to eliminate or reduce ACEs in communities, especially in marginalized communities, but we can identify positive things that can counteract the adversity,” she added.

Narayan recommended that health care providers screen for BCEs, if they’re screening for ACEs. And they shouldn’t just focus on the child, but also query the parent about their childhood. Asking about positive experiences can help adults reframe childhood memories and positively shape their parenting, potentially disrupting intergenerational trauma.

Narayan said that ACEs information in the media, including from the Centers for Diseases and Prevention (CDC), is often inaccurate or overly simplified. For example, the difference between correlation and causation is rarely explained. For ACEs, correlation means these adverse experiences are associated with a risk of poor health outcomes, not that they cause illness. The distinction is subtle but important.

“The message that the public has gotten is that your ACEs score is going to determine the course of your life, which is totally faulty,” said Narayan. “How do we make the message (about ACEs) not just doom-and-gloom?”