Amid 'stubbornly high' childhood poverty rates, the brain drain comes into focus

If you write about children’s health, there’s a good chance you already wrote a story this week that regionalized some of the findings from this week’s release of the 2015 KIDS COUNT Data Book, an annual report from the Annie E. Casey Foundation. Reporting on the latest Data Book findings is an annual ritual in many newsrooms.

One of the over-arching themes of this year’s report is the persistence of high rates of childhood poverty, despite the improving post-recession economy. From the report:

In 2013, nearly a third of children (31 percent) were living in families where no parent had full-time, year-round employment. The child poverty rate has remained stubbornly high. At 22 percent in 2013, it was still several percentage points higher than before the recession.

And a significant percentage of those kids — 14 percent — are living in areas of concentrated poverty, where poor families are densely clustered. These ongoing trends are an urgent problem, since we can now point to a wealth of research that shows how growing up in poverty can exert lifelong shaping effects on one’s overall health, lifespan, language acquisition, economic outlook, environmental exposure, and so on. Poverty sits at the losing end of most every health disparity imaginable, as the report explains:

When very young children experience poverty, particularly if that poverty is deep and persistent, they are at high risk of encountering difficulties later in life — having poor adolescent health, becoming teen mothers, dropping out of school and facing poor employment outcomes.

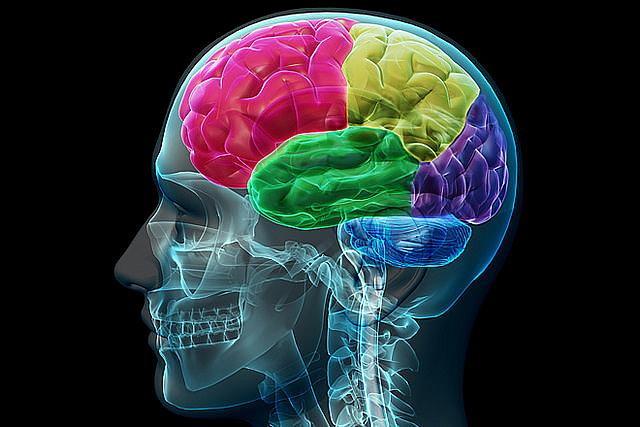

As if on cue, JAMA Pediatrics provided the exclamation point this week with a new study and editorial on childhood poverty and its effects on brain development and school performance. For the study, researchers looked at MRI brain scans from 389 U.S. children and young adults over six years and also examined their family income and performance on academic and cognitive tests. When they analyzed the results, researchers found several critical regions of the brain were smaller by volume among children with higher levels of poverty:

Regional gray matter volumes of children below 1.5 times the federal poverty level were 3 to 4 percentage points below the developmental norm. A larger gap of 8 to 10 percentage points was observed for children below the federal poverty level. These developmental differences had consequences for children’s academic achievement. On average, children from low-income households scored 4 to 7 points lower on standardized tests.

The accompanying editorial’s headline captures the thrust: “Poverty’s Most Insidious Damage: The Developing Brain.” The article’s author, Dr. Joan L. Luby of Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, writes that the new research offers “powerful evidence of the tangible detrimental effects of growing up in poverty on brain development and related academic outcomes in childhood.” Pointing to a growing body of brain research, as well as economic studies from Nobel laureate James Heckman, Luby argues that we now have an “unassailable body of evidence” that can and should guide public policy. She writes:

Given that an alarming 22 percent of U.S. children are estimated to be living in poverty, early childhood interventions to support the nurturing environment for these children must now become our top public health priority for the good of all.

While researchers are still studying the most effective ways to combat some of poverty’s worst effects — in the form of toxic stress and childhood adversity — there are already well-established programs, such as the Nurse Family-Partnership, that have reams of scientific evidence supporting their effectiveness in terms of improving outcomes among poor children. But as Nicholas Kristof and Sheryl WuDunn wrote in The New York Times last year, the barriers to action have more to do with funding than science:

So here we have an anti-poverty program that is cheap, is backed by rigorous evidence and pays for itself several times over in reduced costs later on. Yet it has funds to serve only 2 percent to 3 percent of needy families. That’s infuriating.

Whether this week’s stark new brain research and stubborn child poverty statistics will help translate that abiding fury into forward-thinking public policy remains to be seen.

[Photo by Allan Ajifo via Flickr.]