Boy’s battered feet offer harrowing image of migrants’ journey

Last fall, an 8-year-old boy I’ll call Mateo came to the pediatric clinic in South Los Angeles where I was working. He was thin, with sun-parched skin and very quiet. He seemed fearful of everyone and everything. His mother brought him in because his feet were hurting.

When I removed Mateo’s tattered tennis shoes and socks, his feet were inflamed and the skin was flaking off the soles. His toes were covered in black eschars, pieces of dead tissue. I couldn’t believe he was able to walk.

I asked what sports or activities had he been doing. Speaking Spanish, his mother reported that they had walked across the desert to get to the United States. He had been wearing the same worn shoes that I took off during the visit. His feet got sweaty and badly chafed during the long journey, but he hadn’t complained of pain until the end. They had arrived in Los Angeles the previous week. They left Guatemala because Mateo’s father abused both of them, physically and emotionally. The father was getting more violent and she feared that he might kill them.

So they fled.

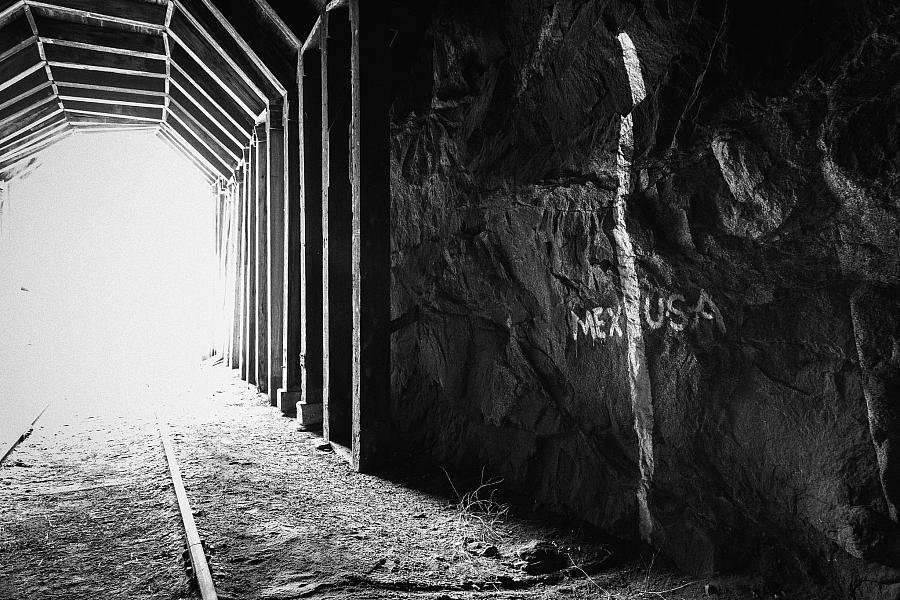

In recent weeks, a caravan of Central Americans walked to the U.S.-Mexico border. The group of more than 5,000 migrants are stuck there, hoping to request asylum. Many of them are women and children like Mateo and his mother, searching for safety. They are victims of their circumstances, born into poverty or living in gang-infested, corrupt communities. Many are also victims of violence.

The number of migrants seeking asylum in the U.S. from Central America’s Northern Triangle region of Honduras, Guatemala and El Salvador has skyrocketed since 2013, surpassing in number the previous 15 years combined. Researchers have attributed this surge to the uncontrolled violence ravaging the area.

Approximately 25 percent of children in the U.S. live in an immigrant family. These children are more likely to live in poverty, suffer food insecurity, have lower academic achievement, and their parents are often less educated, according to a report from the Anne E. Casey Foundation. Growing up in poverty is associated with increased risk of exposure to violence.

Witnessing violence or living in fear of losing a parent (after a divorce or incarceration, for instance) are examples of adverse childhood experiences, or ACEs. Such adverse experiences are correlated with a host of potentially lifelong physical and mental health problems.

Such traumatic events trigger the body’s stress hormones, such as cortisol and adrenaline. These chemicals are necessary for the body’s “fight or flight” response to danger. However, chronic elevation of the stress hormones is caustic. Such “toxic stress” undermines a child’s sense of safety and well-being, and is detrimental to brain development. Children who suffer such stress are more at risk for developmental delay and poor academic performance. And these traumatized kids often have less access to the kind of health care and mental health services that could address trauma’s effects.

Refugees and some asylum seekers may enroll in Medicaid, and documentation of citizenship is not a requirement to enroll in the Children’s Health Insurance Program, or Medi-Cal, California’s version of Medicaid. However, some foreign-born children are not eligible for other government programs, such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, formerly known as food stamps), Women, Infants and Children Food and Assistance Program (WIC) and housing assistance.

His mother described Mateo as a “good boy.” She reported that he had always been small. They never had much money for food. She also said that he didn’t talk much and when he did, it wasn’t easy to understand. He was behind in school in Guatemala.

Mateo was given medication for his feet and a return appointment to monitor their healing and for a complete physical exam. He and his mother were also referred to mental health services. His injured feet were easy to treat, but caring for his psychological trauma would be more challenging. He continues to see a therapist.

Mateo’s story is a reminder that children don’t immigrate, they flee.