Can harm reduction save lives and improve health of drug users?

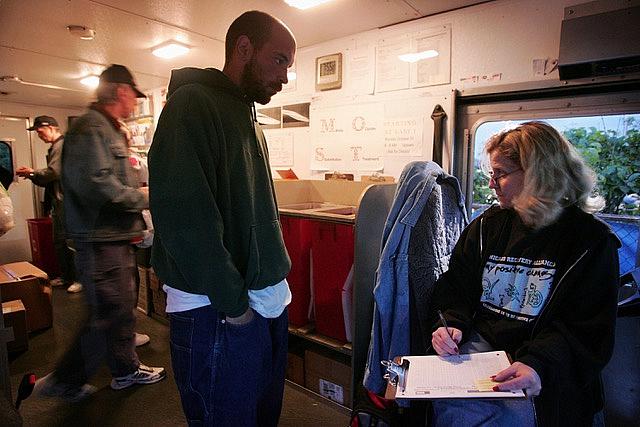

An intravenous heroin user is questioned before receiving hypodermic needles and other injecting supplies at a mobile outreach site. (Photo by Scott Olson/Getty Images)

People have a lot of reasons for using illicit drugs. Some are treating undiagnosed mental illness with opioids, stimulants or both. Others use them to relieve pain. Still others simply enjoy the mood-altering high of a certain substance, be it psychedelic or stimulant.

Some literally need that high to function in their particular worlds: Women who are experiencing homelessness, the journalist Stacey McKenna found in a 2013 survey, might use methamphetamine to stay awake at night on the street, when their bodies and possessions are most at risk from assault and theft.

The problem, of course, is that people who use drugs that haven’t been prescribed for them — or misuse drugs that have — are almost always endangering their health and safety. If the drugs themselves don’t cause hallucinations and psychotic breaks, the dangers associated with obtaining and ingesting them can at least make them sick, if not kill them. Street drugs come contaminated with potentially lethal additives. Shared needles (or pipes or even rolled-up dollar bills) spread disease. Dosing often requires guesswork. And guesswork, as the drug overdose rate in California proves, can be deadly.

In some version of a perfect society, the solution to the health risks of drug use is to end the use of mood and mind-altering substances altogether. There would be treatment programs that worked for everyone, and no need for any of us to alter our brains in order to stay sane and alive.

But that’s a unicorn goal. Nearly everyone in the United States uses drugs in some form, be it alcohol or a daily antidepressant. No culture since the dawn of human existence been completely drug-free. A more realistic ambition, say some health professionals, is to reduce the harm of drug use without shaming the drug user or coercing her into, say, a 12-step program that works for just a fraction of participants. “Tough love,” according to journalist and author Maia Szalavitz, often does more harm than good, by worsening the sense of alienation that drives many people to drugs in the first place.

Harm reduction, a term that arose in the UK around heroin users in the 1980s, includes clean-needle exchanges, where drug users can obtain fresh, unused syringes, and safe injection sites where they can use drugs in the presence of trained medical personnel who can halt an overdose with naloxone, a drug that reverses the effect of opioids. It might also involve the distribution of testing strips that will reveal the presence of fentanyl, an opioid 50 to 100 times more potent than morphine, in samples of heroin or even methamphetamine.

Harm reduction advocates can also tend to less obvious problems in the lives of drug users (whom many harm reduction practitioners refer to as their “consumers”). Community wellness centers that specialize in drug-use disorders can diagnose and help treat diseases such as heart disease and diabetes, both of which are common to chronic drug users. They can also provide job and mental-health counseling services. Sometimes those services lead a drug user toward treatment. Sometimes they don’t. Getting off drugs isn’t the point of harm reduction. Staying alive is.

With support from the Center for Health Journalism’s Impact Fund, I intend to explore what’s being done in California to reduce not just overdose deaths but the health and safety threats that come with using and misusing drugs. I’ll look into the stigma associated with drug use that discourages people who use drugs from seeking help, and the ways in which harm reduction can extend into the community at large, by reducing drug litter on the streets. I’m especially interested in harm reduction efforts that serve poor and isolated communities, where the rates of drug overdose are the highest in the state. Syringe exchanges and overdose kits aren’t always reaching rural California, but I’ll talk to some of the people who are trying to make that happen. The first of my three stories, all for the online news site Capital & Main, will run in mid-July, with multimedia and community outreach to follow.