Sacramento Schools’ Black Student Suspension Rates Remain High Despite Promises — And a Legal Settlement

The story was co-published with the Sacramento Observer as part of the 2025 Ethnic Media Collaborative, Healing California.

Charlotte Banks faced several obstacles to get her daughter Riley the learning accommodations she needed while a student at Sequoia Elementary. When Riley was bullied, she was the one disciplined for defending herself while the other students went unpunished. Riley’s experience mirrors that of many Black students who are overdisciplined in Sac City Unified and Elk Grove Unified school districts, which still have some of the highest suspension rates for Black students in the state. Roberto Alvarado, OBSERVER

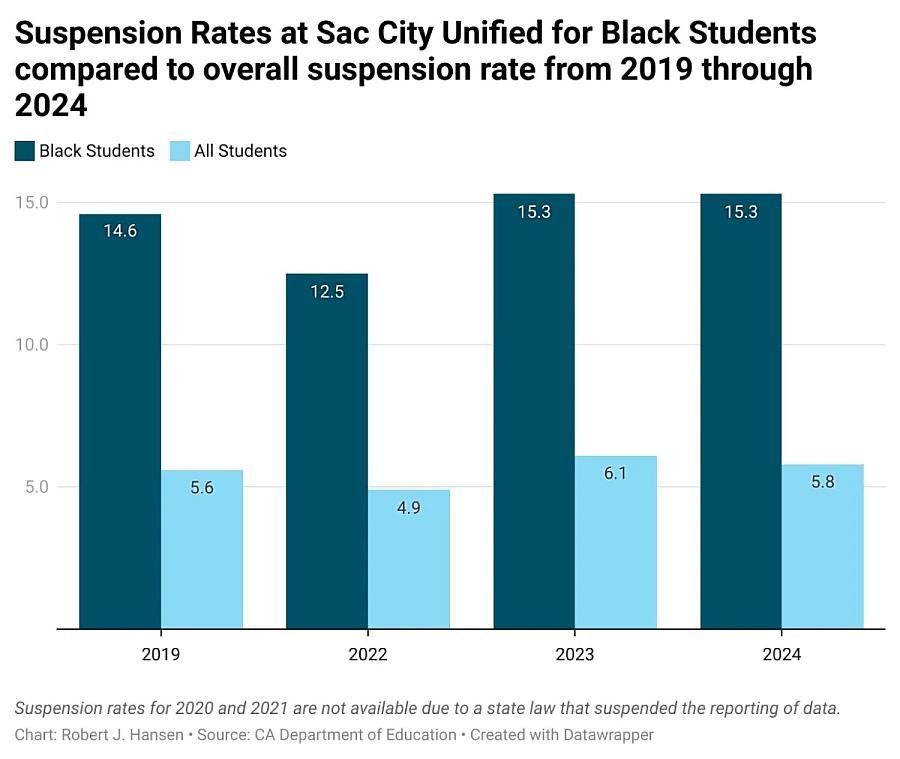

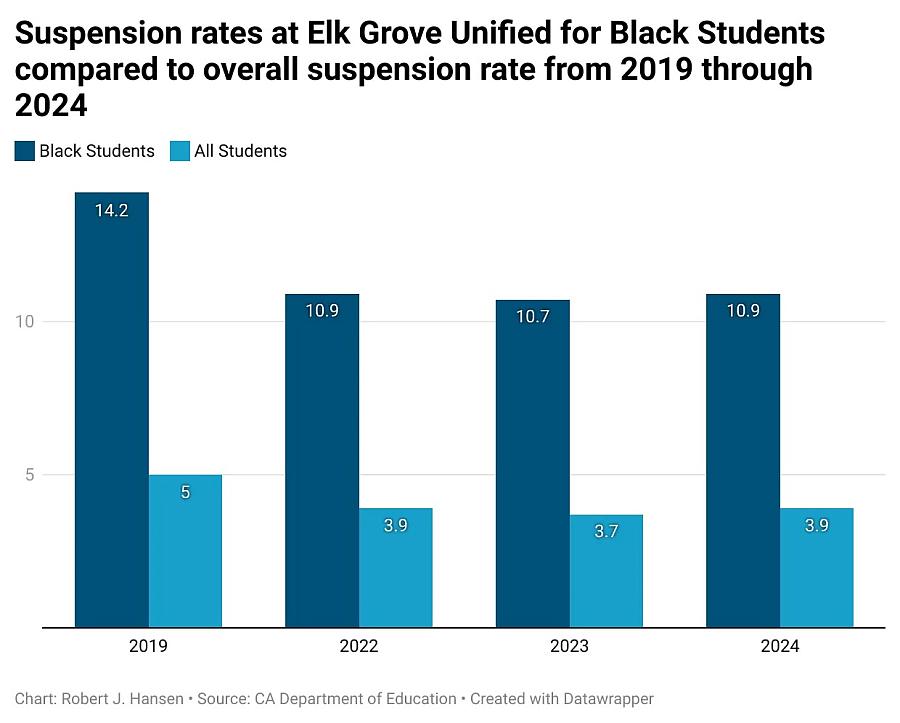

Despite years of pledges to address systemic racism and discriminatory discipline practices, the most recent state data show that two school districts, Sacramento City Unified and Elk Grove Unified, continue to suspend Black students at some of the highest rates in California – rates that increased from 2022 to 2023 and remained unchanged through the 2024 school year.

According to the California Department of Education, Black students in Sacramento City Unified were suspended at a rate of 15.3% in 2023, an increase of close to three percentage points from the previous year.. That number held steady into 2024. In the Elk Grove Unified School District, nearly 11% of Black students were suspended, almost triple the district-wide average of about 4%.

Suspension rates in Sac City Unified for Black students compared to the overall suspension rate, 2019 through 2024. Robert J. Hansen, OBSERVER

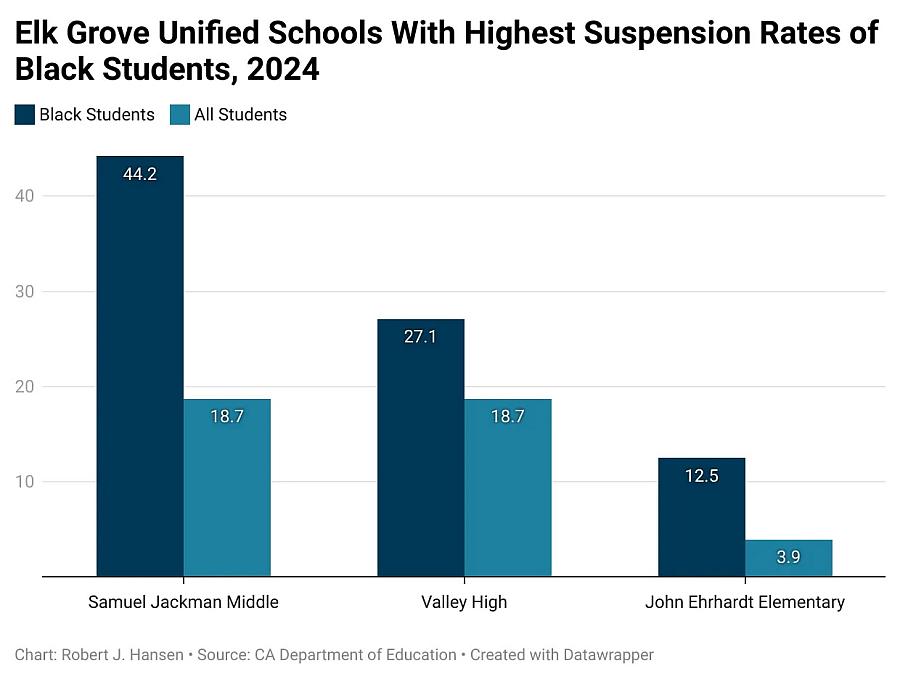

John Ehrhardt Elementary, Samuel Jackman Middle and Valley High had the highest suspension rates for Black students in Elk Grove Unified in 2024. Robert J. Hansen, OBSERVER

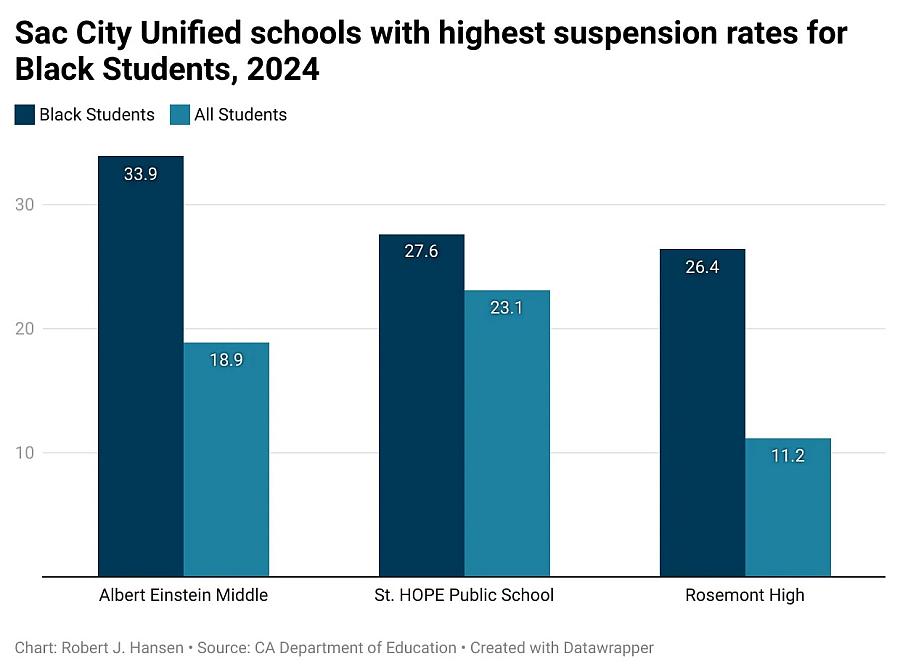

Rosemont High, Albert Einstein Middle and St. HOPE Public School had the highest suspension rates for Black students in Sac City Unified in 2024. Robert J. Hansen, OBSERVER

John Ehrhardt Elementary, Samuel Jackman Middle and Valley High had the highest suspension rates for Black students in Elk Grove Unified in 2024. Robert J. Hansen, OBSERVER

The figures come years after both districts were identified in 2018 as among the worst in the state for disproportionately disciplining Black students. Yet the disparities persist, raising questions about the effectiveness – and sincerity – of promised reforms.

Dr. Luke Wood, president of Sacramento State, authored research in 2018 that found Black students, particularly those in early grades, are suspended at rates far higher than their peers, with Sacramento County having the highest Black suspension rate in the state.

Wood’s study, “Get Out,” found that Elk Grove Unified ranked No. 1 out of nearly 1,000 districts for its disproportionate suspension rates and Sacramento City Unified ranked third.

“Sacramento is ground zero when it comes to both total suspensions and suspension rates,” Dr. Wood told The OBSERVER in 2021. “It’s by far the most egregious suspension county in California, particularly when it comes to Black males.”

Wood has an intimate understanding of the impacts of racial discrimination in schools. Along with his twin brother Josh, he was raised in McCloud, a small lumber town in Northern California. As two of the only Black students at McCloud Elementary, Dr. Wood and his brother endured relentless bullying. When they tried to defend themselves, they were punished, often suspended for trivial reasons.

Dr. Wood told The OBSERVER that he was suspended 42 times in fifth grade while his brother was suspended 24 times. “They had a desk set up for me outside the principal’s office,” he remembers. “The suspensions were triggered by small things. I’d turn around in my seat and I’d be suspended. The teacher would ask you to raise your hand and I’d blurt out an answer and be suspended. If a bully pushed me in class and I pushed back a little bit, I would be the one punished, not him.”

Dr. Wood told Loreeen Pryor of the Black Youth Leadership Project on her podcast last year that the patterns he observed then still exist. Elk Grove still holds the title for the worst district for suspending Black students in terms of numbers and rates, he told Pryor.

Lisa Levasseur, executive director of communication for Elk Grove Unified, told The OBSERVER the district has been focusing on lowering suspension rates for Black students, foster youth and students with disabilities, the three subsets of students that had the highest suspension rates throughout the district.

Levasseur said that in 2023 the district implemented restorative education practices and claimed that has brought down the suspension rates for Black students across the district to 6% for the first half of the 2024-2025 school year.

Charlotte Banks smiles at her daughter Riley, who had to seek counseling after her experience as a student at Sequoia Elementary. Riley just completed sixth grade and looks forward to middle school. Roberto Alvarado, OBSERVER

“Across the district we have trained all of our teachers and all of our leadership on restorative practices,” Levasseur said. “It’s a huge initiative … it focuses on empathetic listening, building relationships, restorative dialog, effective communication, community building.”

She also attributes the decline in suspension rates for Black students to implementing professional development and culturally relative practices, connecting students to feeling seen, heard and valued in the classroom.

In Sacramento City Unified School District (SCUSD), the issue extends beyond suspension rates. In 2019, the Black Parallel School Board and parent Larayvian Barnes filed a lawsuit against the district, alleging that it discriminated against Black students and students with disabilities by funneling them into restrictive, segregated classrooms and denying them equal educational opportunities. The lawsuit cited a 2017 district self-audit that exposed long-standing harmful practices.

Barnes, an educator and mother of three SCUSD students, said the problems became clear when her youngest son began kindergarten. Despite clear developmental concerns, the district evaluated him and wrongly concluded he did not have autism. By first grade, his teacher told Barnes, “I don’t see where he fits in my class.” Her son was frequently sent out of the classroom, disciplined for behaviors related to his disability, and denied appropriate modifications. He was suspended nine times in third grade alone, missing a total of 17 school days.

In 2023, after years of advocacy, SCUSD reached a landmark settlement with the Black Parallel School Board. The agreement lays out a five-year corrective action plan monitored by an independent third party. The district committed to reducing segregation of students with disabilities – particularly Black students with disabilities – and to increasing their inclusion in general education classrooms. It also promised to reduce disciplinary referrals, improve staff training, and better assess and support students’ behavioral needs.

Mona Tawatao, an attorney with the Equal Justice Society who helped lead the litigation, said the core mission of the settlement is to significantly reduce the disproportionate discipline and exclusion of students with disabilities, especially Black students with disabilities. “When we filed the lawsuit in 2019, Black students with disabilities were 11 times more likely to be suspended. That level of disparity is grossly disproportionate,” she said.

Tawatao emphasized that while the settlement aims to improve conditions for all students, it focuses on those who are most severely impacted by exclusionary practices. “We don’t want any student to be disproportionately disciplined, but we’re focused here because the numbers are so out of whack,” she said. These disparities not only contribute to stigma and isolation, she added, but also signal that these students are not being treated as equals. “In segregated settings, they’re not getting the same opportunities or activities as their classmates, and that’s not acceptable. It’s contrary to what the Americans with Disabilities Act and other civil rights protections guarantee.”

A key part of the agreement is ensuring that students with disabilities – especially Black students with disabilities – can learn alongside their peers in what’s known as the “least restrictive environment.” Tawatao explained, “Students with disabilities should be learning with their nondisabled peers whenever possible. We want all students to learn together. Separate is not equal.”

Tawatao also pointed to how systemic bias manifests in disability identification. “Black students are overidentified as emotionally disturbed,” she said, referring to a category of disability that includes mental health conditions associated with challenging behaviors. “We need to ask why that’s happening. Why are Black students being labeled this way more than others?” Such overidentification can lead to more restrictive placements, increased disciplinary action, and heightened stigma, further compounding the inequities the settlement seeks to address.

Since the five-year action plan officially began Sept. 5, Tawatao said there has been “some important progress” made, though she acknowledged more urgency is needed. “We all wish things were moving more quickly,” she said.

This action plan includes 22 specific directives, which provide a framework for reducing Black student suspensions and in-class segregation of students, correcting the over- and underidentification of Black students in special education, and serving all students in the least restrictive environment, among other improvements.

The district will also engage in monthly monitoring of student discipline data, including in-school and out-of-school suspensions to determine what additional measures may be needed at a school site. In addition to the action plan, Sac City Unified continues to provide antiracist and anti-bias training for all staff and to incorporate more restorative forms of discipline.

Tawatao said the pace of reform shouldn’t be surprising considering that suspension rates of Black students remains disturbingly high.

“There are still things happening in the district that are the very reasons the plaintiffs filed this case in the first place,” she said.

She added that the slow pace of change reflects the persistence of bias and racism embedded within the structure of the school system itself. “It’s heart-wrenching. It’s not good. It speaks to how deeply these patterns are built into the way things function.”

A 2024 study found that youth, often Black, Latino and Native youth, who were suspended and expelled exhibited significantly higher depressive symptoms in adolescence when compared to their counterparts with no history of suspension or expulsion, a depressive gap that widens in adulthood.

“Emerging evidence also demonstrates that the cascade of consequences tied to exclusionary discipline shapes important social outcomes in later life,” the authors wrote.

Those who experienced exclusionary disciplinary practices had an increased risk of criminal legal contact in adulthood, contributing to the school to prison pipeline, according to the authors.

Other studies found that youth who were suspended between grades 7-12 were more likely to report a history of incarceration in adulthood.

“Taken as a whole, we argue that due to the myriad of direct and indirect social harms associated with exclusionary discipline, this punitive form of school punishment is a stressor that has the potential to shape mental health patterning in adolescence,” the authors say.

In an email, Sac City Unified said it continues to work diligently to bring greater equity to its student disciplinary process, which historically has resulted in disproportionately high suspension and expulsion rates for our Black and African American students.

Spokesperson Al Goldberg said the district finds the data unacceptable and that its commitment to systemic change is reflected in its collaboration to implement the action plan that resulted from the BPSB settlement.

“We feel confident the changes that are already in place will show demonstrable progress in the near future and result in better outcomes for all our Black and African American students,” Goldberg told The OBSERVER.

Charlotte Banks, another Sac City Unified parent, shared a similar story about her daughter Riley, now 12 and in sixth grade, who recently had to find counseling because of trauma she had experienced at school. Riley began struggling as early as second grade at Sequoia Elementary but Banks said she faced constant obstacles trying to get her daughter the support she needed. “Riley just needed help I didn’t always know how to ask for,” she said. “But the school wasn’t doing their part either.”

At the time, Riley attended an after-school program that was supposed to help with homework, but it turned out her teacher wasn’t even sending the assignments. “I didn’t find out until it was too late,” Banks said. “By the time I got her report, she was already behind.”

Meanwhile, the family had to move unexpectedly, and when Banks tried to get Riley evaluated for learning issues, she said she was bounced between the school and her daughter’s doctor, with neither taking responsibility.

Rosemont High School and the Sacramento County Youth Detention Facility are located across the street from one another, ironically illustrating the school to prison pipeline that many Black lives have been through. Roberto Alvarado, OBSERVER

“It shouldn’t have taken that long,” Banks said. “And it shouldn’t be this hard to get your child the help they deserve.”

Riley didn’t receive an individualized education program (IEP) until the end of second grade. “By then, a lot of damage had already been done,” Banks said.

Even after getting the IEP, problems continued. In fourth grade, Riley was targeted by other students, some of whom bragged about beating her up. “But the school made it sound like she was the one starting trouble,” Banks said. “The principal basically told me she was acting tougher than she could back up. But no one seemed interested in what happened before that – what made her respond the way she did.”

Eventually, Banks got Riley into counseling, which she continued into fourth and fifth grade. Riley no longer attends counseling but remains in Sac City Unified. Barnes still has concerns that her daughter may run into the same bullying in middle school because she could run into the same girls that got away with bullying Riley in elementary school.

Rayvn McCullough, a parent organizer with the BPSB, said the root of the problem – Black students being overly disciplined – lies in how normal childhood behavior is often viewed through a criminalizing lens when it comes from Black students. “Our students might just be messing around,” she said, “but because of the skin they live in, that behavior gets interpreted as threatening or disruptive.” McCullough emphasized that these reactions are not due to flaws in the students, but to institutional neglect that reinforces damaging narratives and exclusion.

She adds that such treatment has a compounding effect on students with disabilities. Repeated discipline can increase emotional stress, causing students to experience depression, school avoidance, or worsening symptoms of underlying conditions such as ADHD. “When students are pushed out,” McCullough noted, “it often worsens their challenges – not because of who they are, but because of how they are treated.”

McCullough also emphasized that needing an IEP or learning accommodations simply means students access curriculum differently, and that public schools are funded to provide those supports. She likened accommodations to wearing the correct prescription glasses: “If a student enters the classroom with the wrong prescription, or none at all, they’re going to struggle to see the board or access information. When our students aren’t given the proper tools or adjustments, they’re not able to fully participate, and then they’re punished for that.”

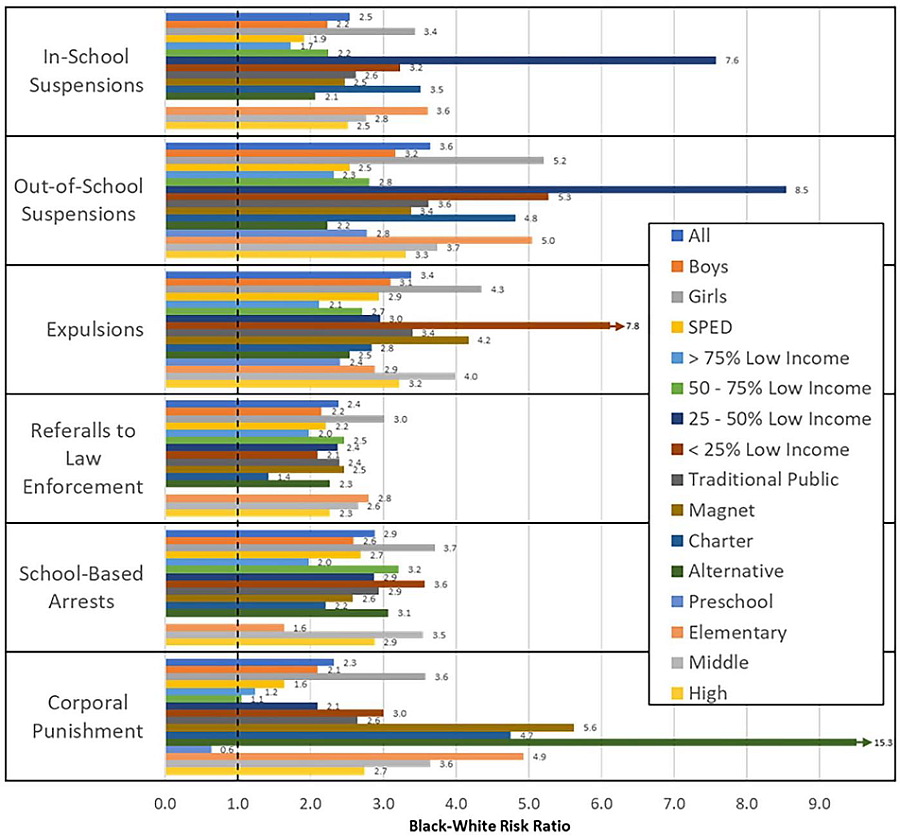

These local experiences are echoed by national findings. A study published in 2024 by UC Berkeley Assistant Professor Sean Darling-Hammond and U.S. Department of Education statistician Eric Ho found that across the U.S., Black students consistently are subjected to school discipline at far higher rates than their peers. “No matter how you slice it, Black students are punished more,” the authors concluded.

The study revealed that Black students were 3.6 times more likely to be suspended out of school than white students, 3.4 times more likely to be expelled, 2.9 times more likely to be arrested on school grounds, and even 2.8 times more likely to be suspended from preschool. In alternative schools, Black students were 15.3 times more likely to be subjected to corporal punishment. Even in more affluent schools – where less than 25% of students received free or reduced-price lunches – Black students faced suspensions at more than five times the rate of white peers.

Outcomes of student discipline for Black students in the United States according to a 2024 study. UC Berkeley

Darling-Hammond noted that these disparities persist despite state and district reforms meant to address them, and that the rescinding of federal guidance in 2018 removed a key safeguard against racial bias in school discipline. He emphasized the long-term damage of such exclusion, citing research showing that even a single suspension dramatically increases a student’s risk of dropping out or entering the criminal justice system.

“When students are disciplined, they behave worse,” he said. “It creates a climate where students are feeling less safe and less connected, which doesn’t benefit anyone.”

As both a researcher and father of two Black sons, Darling-Hammond described the findings as “truly heart-wrenching.” He stressed that children, especially in early education, need connection and support, not exclusion. “Preschool students and elementary school students are so developmentally vulnerable,” he said. “The number one thing that their nervous system needs is acceptance, inclusion, and love. So to see such stark disparities in exclusion and punishment at that stage is truly heartbreaking.”

EDITOR’S NOTE: This article is part of The OBSERVER’s special series, “Crisis Call: Addressing The Mental Health Challenges Of Black Teens.” The project is being reported with the support of the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2025 Ethnic Media Collaborative, Healing California.