A few ideas on how to fix our primary care doctor shortage

Over the weekend, I took a long look at what the health-reform law does to address a looming shortage of primary care doctors. And the short answer is: Not much.

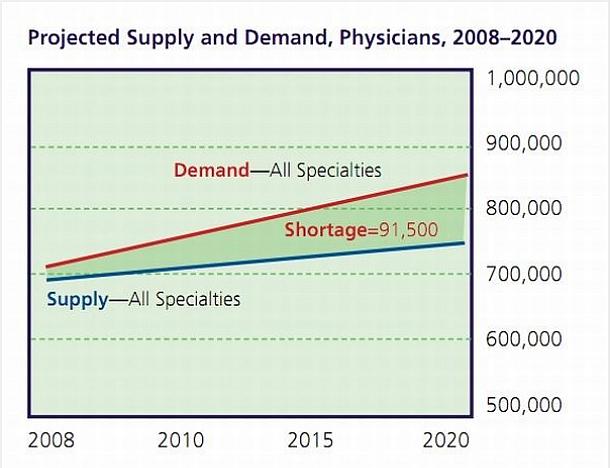

The health reform law has funded a Primary Care Residency Expansion, a $167 million program that will train 889 doctors, as well as $28 million in National Health Service Corps scholarships, for students pursuing primary care careers. That all feels like pretty small potatoes, however, when you look at what we're up against: A projected shortage of nearly 30,000 primary care providers by 2015.

So what should we be doing to increase the supply of primary care physicians? Matt Yglesias suggests building a hospital dedicated to training primary care doctors, easing immigration requirements for foreign doctors and lower Medicare reimbursements to speciality doctors. Aaron Carroll backs allowing other medical professionals, such as nurse practitioners, to do more--known in health policy terms as "expanding scope of practice." This idea also came up a lot in comments on my story, too. "We need a better hierarchy," one reader wrote, "And a review of all salaries in the medical profession because people they are caring for have an average salary of $47,000 a year."

The big question, to me, seems to be one about who will provide primary care in the future. And the policy proposals laid out here could essentially take us in two directions. The future providers of primary care could be the providers of the past, the doctors who have traditionally delivered physicals and preventive services. Or, it could be people who haven't traditionally provided as much care: Doctors who have trained abroad, nurse practitioners and physician assistants.

The policies in the Affordable Care Act look to push us down the first path by making primary care more financially appealing to American medical students who may have eschewed such a career for a more lucrative in speciality. It increases the number of primary care residencies, provides scholarships for American students who serve in rural areas and also bumps up some of the reimbursements doctors receive for providing preventive services.

The policies that Yglesias, Carroll and others have suggested would take us in a different direction, towards a future where our primary care workforce looks a lot different, with a more diverse base of providers. These approaches tend to run into more political obstacles, given that there are many strong medical lobbies that wouldn't like to see the jobs they do performed by others.

The primary care workforce shortage is probably big enough to encompass both policy approaches. A looming shortage of 30,000 primary care providers by 2015 leaves space to bump up the numbers of traditional and non-traditional primary care providers.