The Health Divide: Adult literacy is a public health issue hiding in plain sight

Image

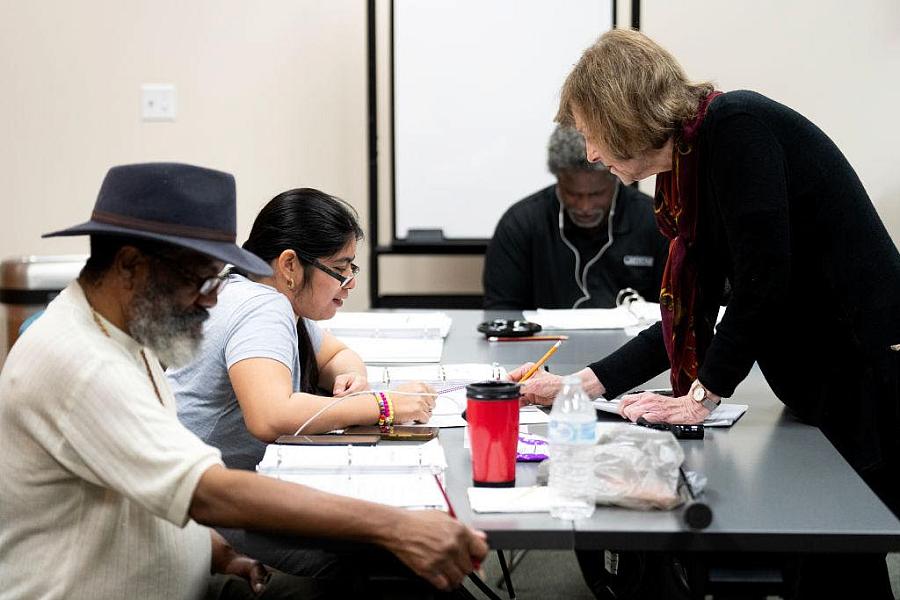

A reading instructor helps a woman decode a series of words during an adult literacy class in Bellaire, Texas.

(Jason Fochtman/Houston Chronicle via Getty Images)

Published on

January 12, 2026

Last September, I visited the Department of Motor Vehicles to obtain a temporary disabled tag for my car, since I had surgery scheduled for a hip replacement. While I waited for my number to be called, I noticed two men in their 60s standing nearby, one Black and the other Hispanic. Both appeared to be struggling with various DMV forms.

When I asked if they needed assistance, they both gladly accepted. The Black man explained that he was having trouble comprehending the questions because he had left his glasses at home and couldn’t read the small print. He asked me to read the questions aloud so he could provide the answers for his form.

After I helped him, the Hispanic man asked for the same help. He didn’t say he had trouble seeing the questions; he just said he couldn’t understand them.

Reflecting on the experience, I couldn’t help but think about how people who struggle with filling out forms might also struggle in other settings, such as health care, where the paperwork can feel endless. These literacy challenges contribute to our significant health divide, since literacy is closely tied to a person's ability to understand, access, navigate, and trust health care services. Low literacy is linked to worse health outcomes — from difficulty managing chronic conditions to higher rates of hospitalization and reduced life expectancy.

My recent trip to the DMV wasn’t the first time I had noticed an adult struggling with reading and literacy. My father faced similar challenges. I first recognized this when I was in junior high school. Whenever he received mail that required a higher level of understanding, he would always say, “Read this to me so I can fully understand it.”

My father, who dropped out of school to serve in the Korean War, may have read at only a fifth-grade level but he had mastered the art of concealment. He secured a job as a welder that provided a livable wage, purchased a home with my mother, and led a comfortable life.

During my father’s peak working years in the 1970s and 1980s, it wasn’t uncommon for labor-intensive jobs to require little more than the ability to follow oral instructions and perform repetitive tasks on assembly lines. The demands of day-to-day work often sidestepped the need for advanced reading skills, allowing people like my father to thrive in a world built on physical labor.

The manufacturing industry has undergone significant changes. Today, employers seek workers who can interpret complex work orders, comprehend detailed labels, and navigate intricate processes. Approximately 38% of U.S. manufacturing firms demand not just basic literacy but also advanced math skills, typically equivalent to those possessed by people with at least a solid high school education. In many cases, a certificate from a trade school or a community college is also preferred.

In my home state of Wisconsin, one in seven adults struggle with low literacy, meaning around 1.5 million adults need help developing foundational reading, writing and math skills. Nationally, about 43 million adults have low English literacy skills. In federal survey data, adults with low literacy include people of every background, with the largest shares split between White and Hispanic adults.

Public schools get blamed, but the problem is bigger

This country’s low adult literacy rate traces back to a mix of social, educational and economic factors that have developed over the decades.

Public education has been the subject of considerable criticism; however, it is essential to recognize that local property taxes are a significant source of funding for K-12 education, in addition to state funding. This financing model results in significant resource disparities, particularly in low-income communities, which often face larger class sizes, a shortage of reading specialists, and outdated instructional materials. These resource-poor schools are, for the most part, in Black and Hispanic communities.

Research indicates that students who do not attain reading proficiency by the third grade are four times more likely to drop out of high school compared to their more proficient peers. And these individuals often continue to experience challenges with literacy throughout their lives.

Brenda Cassellius, superintendent of Milwaukee Public Schools, Wisconsin’s largest public school district, announced in December plans to invest additional funds in struggling schools, including paying teachers more to work in the most challenged schools and finding additional resources to help improve literacy and math comprehension rates. Overall, less than 20% of students meet expectations in English, and less than 15% meet expectations in math.

“When you’re going to a school that is stressed and challenged, kids are very far behind, teachers have to spend a lot more time planning and working with families and home visiting and all of those things,” Cassellius told the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel.

While addressing public education is a start, the country clearly needs to do more work to help adults who struggle to read, write, and understand on a daily basis. While some community colleges, libraries, faith centers, and nonprofit organizations offer free or low-cost programs to improve adult literacy, these initiatives do not reach enough people. And few policymakers are advocating for more attention or resources to bolster flagging literacy levels.

One report found that most people who need these services either don’t know they exist or, if they do, face barriers such as work schedules, transportation, and childcare that prevent them from attending classes or tutoring sessions.

Literacy rates are tied to incarceration

Journalists looking for fresh story ideas should consider reporting more on the adult literacy crisis, making it feel urgent and difficult for policymakers to ignore.

While statistics indicate that more than 43 million adults struggle to read at a third-grade level, numbers alone rarely sway public opinion. It is essential to illustrate how these individuals face challenges in navigating daily life due to low literacy skills.

Emma Gallegos, a Data Fellow at the Center for Health Journalism, has reported extensively on adult literacy and shared strategies for covering the undercovered issue. “It was devastating to hear one source say he was shocked to see a reporter care to write about a subject that, in California, largely affected Latinos in rural areas,” Gallegos writes. “This population feels invisible.”

Many adults find it challenging to fill out medical forms, understand workplace safety guidelines, or recognize online phishing schemes, and may become victims of fraud and scams. Even more concerning, they may struggle to help their children with homework.

Literacy rates are closely linked to incarceration. While we talk about “mass incarceration,” it’s important to note that according to federal data, more than 70% of the U.S. prison population falls into the lowest tiers of literacy proficiency, meaning they lack the reading and writing skills typically required to navigate modern workplace demands.

Journalists looking to track these issues should report where their state ranks in adult literacy, determine how much funding is dedicated to addressing the issue in their governor’s budget, and compare that to other states. The results could be eye-opening for audiences and policymakers.