The Health Divide: America has a gun violence problem, and youth must be part of the solution

Nevaeha Ware raises her hand to talk about the shooting death of her brother.

Photo credit: James E. Causey

America has a gun violence problem, and children are often caught in the crosshairs. Gun violence must be treated as a public health crisis because America cannot police or incarcerate its way out of the problem and will not legislate to keep people safe.

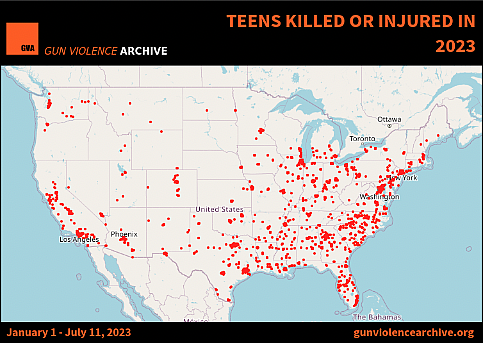

Five children under 17 die from gun violence daily, and 14 more are shot. So far this year, 960 kids have been killed, while 2,564 were shot and injured, according to the Gun Violence Archive.

In my hometown of Milwaukee, 13 kids have been shot and killed since July 5. That puts the city on pace to tie, or surpass, its previous record of 2, set just last year.

Youth gun violence touches all of us. It touched me when Nevaeha Ware’s life was cut short at 13.

Nevaeha was shot and killed in January 2021. To this day, Nevaeha’s family has not received closure because her shooter has yet to be caught.

I interviewed Nevaeha in 2017, when she was 9. I was working on my project, “What Happened to Us,” to see how much had changed for third graders since I attended Samuel Clemens Elementary School as a third grader in 1978.

I met five children, third- and fourth-graders — four girls and one boy — in the school’s library. We sat together at a table, and I asked each student general questions to break the ice. I told them I had attended the same school 40 years earlier and was now around the same age as their parents, if not older.

When I asked the group if they had experienced or witnessed violence, the mood at the table changed.

"How many of you have been bullied?"

Four hands.

"Bullied daily?"

Three hands.

"How many of you have witnessed violence in your neighborhood or household?"

Five hands went up.

"How many of you have a family member incarcerated, shot or killed?"

Still, five hands.

Nevaeha told me her brother Qwaishaun had just been shot and killed.

Her wide eyes watered up.

“I’m hurt and sad,” Nevaeha said. “I don’t know what happened because I was at my auntie’s house when it happened.”

She paused.

“I just know I miss him.”

Qwaishaun, whom she called Qwaish, had been shot in the head. He died in the hospital a day later.

Her mother allowed her to stay home from school, but she wanted to go.

Her teachers knew something was off with Nevaeha when she failed a math test. She never told them about the mental trauma she was experiencing. Like most schools in Milwaukee, Clemens didn’t have mental health counselors on staff.

“I want to be a doctor when I grow up because too many kids in this city die, and their friends don’t have anyone to talk to about it,” she said. “I want to be there for them. We all need someone to talk to. Sometimes we need to cry.”

Just over three years later, Nevaeha snuck out of her house to see a boy. She called friends for a ride home. She never made it.

When her friends arrived at the boy’s house, she got in the back seat with other young people. The driver got into an altercation with someone in another car. Shots were fired. A bullet went through the trunk, striking Nevaeha right above the heart.

What I remember the most from Nevaeha were her cries that went unanswered. She wanted someone to listen to her. She wanted to be heard.

Today, many teens say they still are not being heard.

Suicide, self-harm, and depression are on the rise among U.S. teens. In 2019, 13 percent of adolescents reported having a major depressive episode, up 60 percent from 2007, according to the New York Times.

While many programs, groups, and agencies target youth violence and mental health, the teens I’ve talked to say most don’t work because they fail to seek input from youth

I recently attended a youth panel, “Fostering Hope Through Violence Prevention,” hosted by Bader Philanthropies in Milwaukee. The event was billed as an opportunity for local youth to be heard by business leaders about what they need to succeed and keep them safe over the summer.

Larry Dorsey, 18, was one of four students on the panel. He said adults rarely ask him for his opinion on youth issues.

“They think they got it figured out, but they don’t. How can you address any issues with youth without talking to the youth? You can’t,” he said.

Dorsey and all the youth said young people want more mental health counselors, Black and brown teachers, and school mentors, and the Wisconsin legislature's response is to provide more police and safety aides.

“It’s so frustrating. It’s like they listen but then do the opposite. They pretend they know what we need based on studies and reports. This constantly happens, which is why things keep worsening,” he said.

Adults are taking a study and building a program around it to address youth issues but have yet to ask local youth for input beyond the analysis or report. It’s no wonder most of these programs fail to get results. There’s plenty of talent, love, and care in the communities that too many of us in society write off. However, the distribution of resources to serve our communities keeps missing its target for a lack of listening to those most impacted.

Adults must listen to young people and go beyond the data. Leaders must give young people a seat at the table before any plan goes forward.

That’s where journalists play a critical role.

Sharlene Moore, executive director at Urban Underground, attended the panel and said the youth have spoken. Now it’s up to the adults to address their concerns. Urban Underground differs from other youth programs by turning teens into change agents in their neighborhoods.

“The time is now to do something,” she said. “If we don’t give these kids mental health counselors, mentors, and more teachers of color whom they can relate to, what are we doing?”

As journalists, we have the reach and power to change narratives and hold people accountable. Adults need to listen to young people, and we must elevate their voices.

I want people to be activated by what I write. This is how you can become activated and do your part to keep young people safe and mentally well.