Here's what our expert panel said about tackling COVID misinformation

At the onset of the pandemic, the ground was fertile for misinformation.

While the new virus rapidly circulated, scientists scrambled to figure out how it spread, whether it was airborne and how to treat it.

“It created this enormous uncertainty vacuum,” said Carl Bergstrom, a professor of biology at the University of Washington whose work has examined the spread of disinformation on social networks. “Into that uncertainty vacuum came flowing a whole bunch of things.”

While more and better information has accumulated over the past year, misinformation and lies are still propagating on everything from mask wearing to the COVID-19 vaccine.

Bergstrom joined Dr. Melissa Clarke, an emergency medicine physician and co-founder of the group Black Coalition Against COVID-19 and Rae Ellen Bichell, a Colorado correspondent for Kaiser Health News to discuss the pandemic’s tsunami of misinformation and efforts to combat it in the most vulnerable communities.

Tackling misinformation

The pandemic changed the culture of communication among scientists, Bergstrom said. Researchers wanted to work rapidly and share information without the usual peer-review process. That led to a flood of preprints — papers shared online before peer review.

“Unfortunately, some of them were absolutely dreadful,” he said.

At the same time, there were people deliberately creating misinformation on social media. Bergstrom also pointed to journalistic fails, such as headlines that contradicted stories, cherry-picked anecdotes or studies and reporting that didn’t provide a broader scientific context.

“And all of this is all wrapped up in the authority of numbers which are particularly difficult for us to challenge because they seem to come straight from nature,” he said.

Journalists can play a vital role in addressing the misinformation, Bergstrom said. For one, reporters can help people develop a better understanding of what the wealth of numbers around COVID-19 mean.

He also advised journalists to accept uncertainty and explain why it isn’t possible to pin something down precisely, such as the exact infection fatality rate at the start of the pandemic. Researchers just didn’t know, and smart estimates varied widely.

“While certainty makes for better headlines, it doesn’t accurately reflect the situation,” he said.

When covering preprints, interview outside experts and set the new studies in the context of broader scientific literature, he said. A new study doesn’t eradicate what came before. Consider each new study as a small pebble in support of a given hypothesis, he said.

That context will also help the public from “getting whiplash, and eroding their trust in science,” he added.

Finally, be wary of anything that sounds too good or too bad to be true. It probably is.

A long history of mistrust

The story of vaccine decisions in some communities of color is a complex one, said Dr. Clarke, who is a member of the expert group advising the vaccine distribution effort in the District of Columbia and speaks widely to community and worker groups about COVID-19.

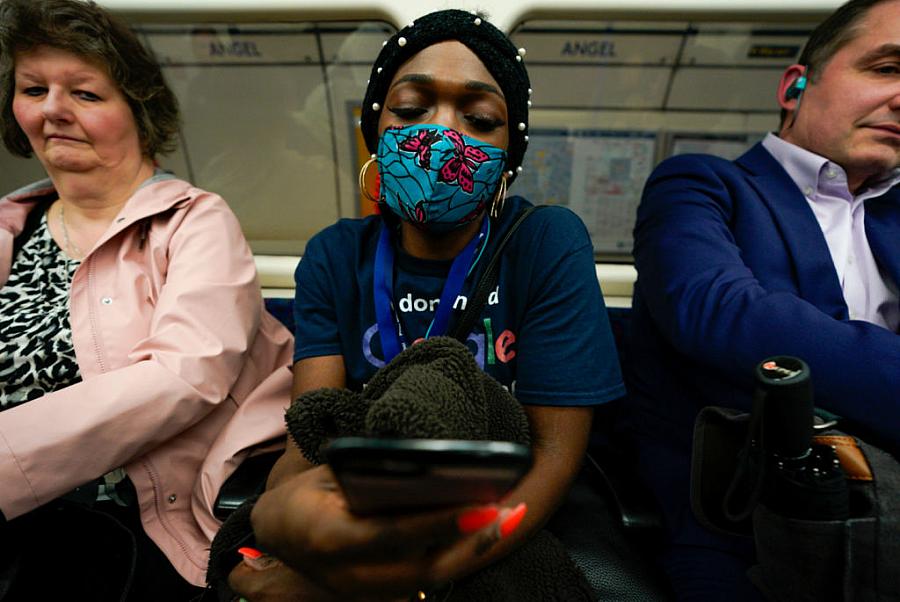

Decades of structural inequities and systemic racism – shaping everything from economic policies to health care delivery – have converged to create an environment of mistrust for communities of color, said Clarke, a leader in population health.

“If you’re trying to say, ‘Trust us,’ you have to have earned that trust,” she said. “And unfortunately, we don’t have a history in this country of earning the trust of the African American community…”

The historic Tuskegee syphilis experiment, in which treatment was intentionally withheld to African Americans, is not the only driver of medical mistrust. She also pointed to contemporary microaggressions in health care, and disparities in access to care or pain treatments.

When you introduce misinformation to communities that already feel mistrust, it finds fertile ground and takes root, she said.

Clarke said many African Americans may want to wait-and-see about the COVID-19 vaccine because they’re less likely to know someone who has been vaccinated, which can in turn influence a decision. And, if they have vaccine questions, many African Americans don’t have ready access to a primary care provider.

It’s also important not to use a broad brush for all African Americans, Clarke said. For example, Ethiopian or Nigerian immigrant communities in the United States may have different attitudes toward vaccines and health care than other African Americans who have experienced a different history.

Understanding a specific community’s concerns makes them easier to address. And discussing the complex reasons why a population might be more hesitant to get a vaccine gives people voice, encouraging them to engage and advocate.

The Black Coalition Against COVID-19 is conducting town halls and connecting with trusted community messengers to spread evidence-based information on a hyper-local level. That’s having an impact, Clarke said, citing internal polling during the group’s town halls suggesting that vaccine concerns have dropped.

Vaccine hesitancy is a mixed bag

Through her reporting, KHN’s Bichell has also found that vaccine hesitancy is not all the same. Areas of the country that have low rates of childhood immunizations may not necessarily correspond to ones with COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy, as she detailed in a story last week.

The groups of people who are becoming eligible for a COVID-19 vaccine are not the same as the more narrow category of parents of young children. There have also been distinct access challenges with the COVID vaccine which is less of an issue with childhood vaccines. And while the broader childhood anti-vaccine movement cut across party lines, some experts worry about increasing politicization of the COVID vaccine. Republicans are far more likely to say they don’t want the vaccine.

It’s also important to distinguish between people who refuse vaccinations versus the ones who are taking a wait-and-see approach as new COVID-19 information evolves, Bichell said.

“People are changing their minds,” she said.

Even with COVID vaccine surveys, the wealth of information from national polls don’t always translate into what’s happening locally. To better report these nuances, Bichell advised engaging with specific communities to see what’s driving decisions, from church leaders to access to advertising.

“The thread ‘local matters’ holds for the Covid-19 vaccine,” she said. “I think there are a lot of opportunities to go really specific,” she said.

Do you repeat the myth?

Bichell said she worries about repeating myths in her coverage – even if she is going to debunk it, she said. Sometimes, the most memorable piece readers may take away is the myth itself, not what follows it. That could further propagate mistruths, she fears.

Debunking misinformation without inadvertently spreading it “takes a little bit of journalistic backflips,” she said.

Even so, it’s important to address and contextualizing the mistruths, said Clarke, who disagreed. All good disinformation has a kernel of truth. To uproot it, it’s important to let people know you know what they may have heard. Then, you can parse the truth by putting that kernel — often misinformation starts with a kernel of truth — in its proper context, allowing people to feel heard.

**

Watch the full presentation here: