How I combined data and trauma-informed reporting to reveal the toll domestic violence is taking on children in Milwaukee

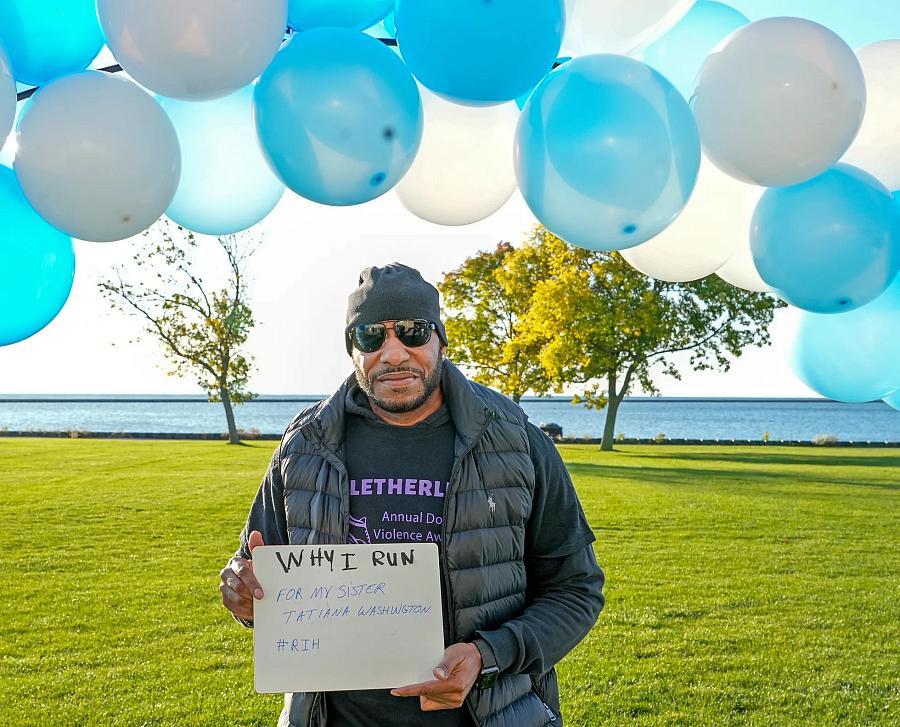

Michael Washington, whose sister was killed her husband, attends a domestic violence walk-run in Milwaukee. His family’s story was featured prominently in Luthern’s reporting.

Photo by Ebony Cox/Milwaukee Journal Sentinel

Domestic violence is everywhere.

About one in four women and one in five men in the U.S. report experiencing intimate partner violence in their lifetime. People of color experience it at rates up to 2.7 times higher than those of their white counterparts.

National surveys show 21% of all violent crime is related to domestic violence.

In Milwaukee, where I’ve worked as a journalist for more than a decade, police data show one in three of the city’s aggravated assault victims — which can include nonfatal shootings, stabbings and serious beatings — were hurt in acts of domestic violence.

The link between domestic violence and mass shootings — and other public space violence — is increasingly well-documented.

And yet, fatal domestic violence can be difficult to track comprehensively.

Police agencies follow strict legal definitions of domestic violence when recording data, while advocacy groups typically include a broader definition that encompasses intimate partner violence, offender suicides and child deaths.

With grant support from the USC Center for Health Journalism’s Domestic Violence Impact Reporting Fund, I set out to investigate the toll of deadly domestic violence in Milwaukee and its ripple effects, including on children. Along the way, I had to navigate challenges on data collection, explain complex definitions to readers, and amplify survivors’ voices in a trauma-informed and ethical manner.

Data can help you tell the story — if you know where to find it

Crime data is notoriously incomplete.

The data are generated by law enforcement agencies and are based on reported crime. That context matters when covering domestic violence and sexual assault, which are historically underreported crimes.

Surveys asking people about crime victimization can provide a more accurate view, as they do not require that a person reported the crime to law enforcement.

To know where to start, it’s helpful to think of all the different agencies that may have a piece of this information.

In my case, I was focusing specifically on fatal domestic violence.

In Milwaukee County, we have a medical examiner’s office that undertakes death investigations in cases of homicide, suicide, accidental or suspicious deaths.

I also knew advocacy groups that help domestic violence survivors often keep their own records. End Domestic Abuse Wisconsin, a statewide coalition, produces an annual report on domestic violence deaths. A domestic violence shelter in northeast Wisconsin keeps a running list of victims statewide based on media accounts.

Those resources helped supplement the data I did receive from police agencies, especially the Milwaukee Police Department. I knew from past reporting that the department kept a detailed spreadsheet of homicide cases, which included “primary factors” for the cases that were solved. Unlike most homicide cases, those related to domestic or family violence usually have a suspect identified very quickly.

I used those sources to start building a custom database. A critical first step was brainstorming the categories I wanted to track. What did I want to learn? What has past research found? My editor at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, Rachel Piper, and I spent one of our weekly check-in meetings dedicated to this task. I wanted to avoid getting mid-way through my research and thinking, “I wish I would have tracked this specific factor.”

I thought about what public records could help me answer these questions. I requested and reviewed thousands of pages of publicly available documents about those cases from circuit court, police departments and the Milwaukee County medical examiner’s office. The review also included media reports.

In particular, I relied on court transcripts of sentencing hearings, medical examiner reports and obituaries to identify if victims had children and if a child had been present during the homicide.

I kept a data diary where I described my process, including how I was categorizing cases and entering data. This eventually became the basis for two sidebars, in which I outlined my process and findings for readers, including the limitations.

All of my findings were conservative estimates. There were almost certainly more cases, but my research was limited to publicly available information. I included only what could be confirmed through public records.

I asked local and national experts to review my findings in advance of publication. The experts said the findings tracked with previous research in other parts of the country and with local trends. When there were differences, they provided explanations and context.

One Milwaukee-based agency included suicide deaths of offenders, whereas I did not. Advocacy organizations also knew if victims had previously sought services there. I understandably did not have access to such confidential information.

Centering survivors and victims’ families with trauma-informed reporting practices

Behind every case, behind every data point, was a person and a family.

I wanted to make sure to honor the voices of the victims’ families and survivors throughout this project. I have years of experience interviewing survivors of gender-based violence and have developed a guide to help me navigate the reporting process in a way that is trauma-informed.

Many of these practices are recommended by the Dart Center for Journalism and Trauma, which offers free tip sheets for journalists on a variety of subjects, including interviewing crime victims and survivors of mass tragedy.

I also am fortunate to have newsroom leadership that supports this kind of reporting. As a policy, the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel does not identify victims of domestic violence or sexual assault without their consent. I do make the person aware that my editor will know his or her name to confirm that I spoke with a real individual and discuss how they want to be identified in the story and the language that will describe why their full name is not being used.

For this particular story, I knew I wanted to revisit a family I had met several years earlier. Michael Washington had been working as a homicide detective in Milwaukee when his sister, Sherida Davis, was shot and killed by her husband, who was a Milwaukee police officer. Her husband then died by suicide. The couple had two sons who were home when the shooting took place and Washington became their legal guardian.

Washington had become more open about sharing his sister’s story and had joined the board of a local nonprofit organization dedicated to preventing domestic abuse. I reached out to him and explained the scope of the project, from the data I was collecting to the stories I was trying to tell. I asked if he would be willing to talk about how life changed for his family after his sister’s death and he agreed. He chose the time and place of the interview, and invited his mother to participate, too.

We spent a couple hours talking together in person. I let them guide the pace and direction of the interview. I explained my publication timeline, which was still a couple of months away, and assured them I would be reaching out before publication to talk through what would be in the story.

Those final phone calls are critical. I never want anyone, whether they are accused of wrongdoing or are a victim sharing their deepest pain, to be surprised by something in a story. In this case, I read through the entire story with Washington so he would know the context. He did offer several fact-checking corrections and additional details in this conversation that made the piece stronger.

I did the same pre-publication calls with other survivors quoted in my piece. Their voices were critical in showing readers how children can be the main factor in survivors’ decision-making. People often stay in abusive relationships because of their children. And when they do decide to leave permanently, it’s typically because of their children, too.

Reading through sections of stories pre-publication is not traditional journalistic practice, but for these kinds of stories, it should be. These are private individuals sharing deeply personal and often painful stories of trauma and resilience. We owe it to these sources and our readers to share their stories in all their complexity.