Housing is transformative for domestic violence survivors, but supply and safety present challenges

The story was originally published by Afro LA as part of larger series, with support from our 2024 Domestic Violence Impact Fund.

If you or someone you know is experiencing domestic violence, call the National Domestic Violence Hotline for help at 1-800-799-SAFE (7233), or go to www.thehotline.org. Operators are available in English and Spanish. If you’re based in California, find a shelter near you.

Per AfroLA’s policy on anonymous sources, Lily’s last name is withheld to protect her identity and safety.*

When Lily first learned of the Downtown Women’s Center’s (DWC) services in 2022, she was hesitant to accept help.

Lily* had been reluctant to accept services or move into an emergency or transitional shelter, she said, because of their strict visitor policies. When she first went to an emergency shelter in 2021, Lily’s abuser found her there and beat her.

“Asking for help was the biggest thing for me, beyond realizing that I’m worth it,” Lily said.

DWC moved Lily to safer transitional housing, where visiting rules prevented her abuser from reaching her. Established in 1978, DWC is the only organization in Los Angeles focused exclusively on housing women and gender diverse individuals experiencing homelessness.

In DWC housing, Lily’s abuser wasn’t able to force his way in, as he had other places she’d been. Lily told AfroLA that the safety of transitional and then permanent housing helped her begin to find community, and a place to heal.

“I started to see the positive side about being here. Sure, I was still using [drugs]. I had to get to know myself and cope with that, but the more I stayed here [in Downtown Women's Center], the more I wanted to be part of the community here,” she said. “I couldn't do that high, so I asked for help.”

Building opportunities

In 2019, unaccompanied women like Lily—women who aren’t looking for safety with children or family—made up 59% of the women housed with DWC’s permanent and transitional housing programs.

Permanent housing is one of the most in-demand services for unhoused people and domestic violence survivors alike. DWC and Jenesse Center, the oldest domestic violence organization for survivors in Los Angeles, have seen an increase in housing needs.

DWC served more than 5,000 women last year, housing many of them in 150 Downtown Los Angeles units and 40 additional units in North Hollywood. But, local organizations that help domestic violence survivors are also tackling the increased need for housing more directly: Building more units themselves.

Jenesse Center piloted a new housing program with the L.A. County Housing Authority and Solaris Apartments, which provides beds and services for individuals fleeing violence and people in need of affordable housing. Together, they built a new apartment housing complex that was completed last year. In August, 43 residents moved in, including 14 domestic violence survivors. The remaining units are occupied by other people who previously experienced homelessness.

Housing provides more than a roof

Apprehensive walk-ins to Downtown Women’s Center’s office on San Pedro Street find a welcoming space. A nondescript 4-story building—white concrete with a small purple awning bearing the Center's name—is located next to a thrift store for women’s clothing, run by the DWC. Warm lights illuminate a small lobby and office space buzzing with caseworkers and other staff.

In 2022, Lily started attending therapy sessions as part of a DWC program that helped her settle into transitional housing, find a job, and eventually move into permanent supportive housing.

Lilly said her therapy taught her life skills beyond how to understand and healthily process trauma. She said she’s learned how to become someone who contributes back to her community.

“[Therapy has] helped me be an adult, a positive productive adult. Because of my rebelliousness and the stuff I went through growing up, I didn't see what I was out there. I was always stuck on Skid Row and on certain parts of the street. But now [that] I'm here, I see Skid Row in a different light,” she said. Her new job as a health care aide, she said, has allowed her to see her potential to help others like herself.

Lily now assists other women as part of the Lived Experience Council for her supportive housing complex. She meets with other women on her floor and in her building to address problems and complaints, share stories, voice needs. Lily credits her ability to do it all—therapy, her job, and embracing her independence—to finding housing.

But housing is a precious commodity. And for the more than 18,330 domestic violence survivors experiencing homelessness in Los Angeles, housing is sometimes the difference between remaining with an abuser, or leaving.

Caseworkers as a critical resource

When survivors first enter DWC’s program, they are matched to a caseworker that will connect them to the services they need. If they request housing as a priority, said Vanessa Gallardo, director of permanent housing, they are screened for internal and external program eligibility. Rapid Rehousing program case managers help clients create a safety plan and talk through their goals, their income and what barriers they might have getting housing.

Caseworkers say the process to acquire housing is long and often confusing for survivors, many of whom are independent for the first time. Caseworkers help survivors understand, complete and file the paperwork to receive permanent housing. Then, they wait. The process can take up to two years.

* * *

Each person who comes to the DWC for services is input into the Coordinated Entry System, a computer algorithm that assigns them an acuity score that assigns and curates services based on their answers to a series of questions.

The higher the acuity score, the more vulnerable the person is presumed to be. That score is used to determine which permanent housing resources the individual is eligible for. The same system is used to place L.A.’s homelessness population, and is controversial because of the way it scores people's needs. According to Gallardo, two of their housing options necessitate both experiencing homelessness and mental health struggles, or homelessness and violence in order to be considered for housing.

If someone is actively fleeing violence, said Goodburn, agencies will assist caseworkers in finding the person a safe place to stay. With shelter, survivors don’t have to be in a “back and forth” about when they can leave, they can focus on the documentation they need to get into supportive housing and permanent living situations. “The process is intricate, and curated to the individual,” said Goodburn.

Caseworkers are required to gather identification documents, income verification, and documented need of services. If a person is fleeing a relationship, documents could be kept by an abuser. Some survivors have been isolated or not allowed to work, or they have experienced financial abuse.

Income verification is not always an equitable process, explained Stephanie Grudberg, director of permanent housing for the Jenesse Center. “If they make this much they don’t qualify. That doesn't tell you what the victim has gone through. If someone makes $10,000 a month but $9,000 of that money goes to domestic violence-related expenses like medical bills, restraining orders, divorce,” she said, “then you have a victim with no income that spends more than someone making $25,000 a year who isn’t a victim, and you have a victim living on $1,000 a month.

Some survivors have been isolated or not allowed to work, or they have experienced financial abuse. Their credit scores and income verification may not tell the whole story. “I try to have these conversations with the big people in the room,” continued Grudberg.

Grudberg said the importance of caseworkers, in this situation, is to provide survivors with someone to support them as they navigate new situations. “Sometimes you can't fix their problem for them, it's comfort knowing someone who can help you get through it,” she said. “You feel the weight is on your shoulder…Women are living in their cars with babies. All you can do is support the best way you can.”

Staying safe in supportive housing

Lily’s account of her abuser reaching her and harming her after she’d fled is one example of risks to personal safety in shelters.

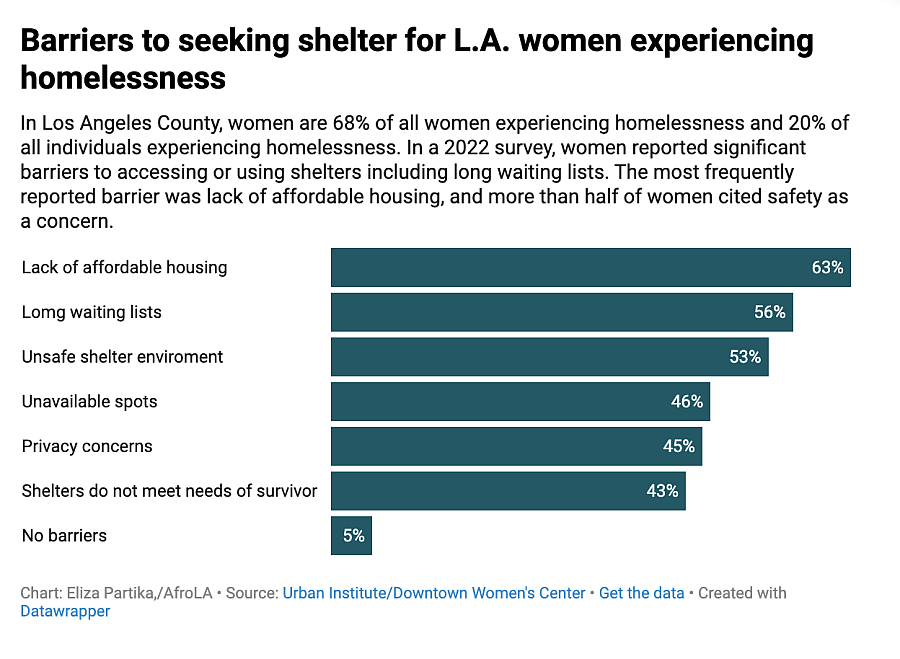

In DWC’s most recent Women’s Needs Assessment, which surveys survivors every two years about their experiences with their services and what they still need, many women shared difficulties of life in a shelter. Some survivors described being assaulted or robbed.

These safety risks aren’t limited to shelter, explained Soma Snakeoil, who helms a street-based harm reduction organization on L.A.’s Skid Row. “Even when survivors get into housing, they're still targeted in housing. And we see this over and over again, whether it's in transitional housing or permanent housing. And you know, it's like what are security guards even for?” she told AfroLA.

Snakeoil, co-founder and executive director of the Sidewalk Project, said former Sidewalk Project participants have been murdered, sexually assaulted and robbed in housing, with nothing done. Safety remains one of the biggest concerns for women being housed in domestic violence shelters, especially co-ed housing.

Sidewalk Project staff got one woman into housing, said Services Director Jen Elizabeth, but her partner kept getting into the housing complex and beating her.

“Security kind of has not been able to get a handle on it, and we've offered self-defense classes, but in the process, you know, women are being targeted,” said Elizabeth. She described another participant targeted for trying to help a friend flee violence. The woman returned home to her supportive housing unit to find all her belongings gone. “Every single belonging in the house was gone, and nobody knows what's happened, and nobody's telling us anything. And apparently the cameras were turned off,” said Elizabeth.

The Downtown Women’s Center said their security is there 24/7 to keep an eye on the women in their care, in addition to the women’s lived experience board Lily is on. Jenesee Center told AfroLA their security is based on the trust the caseworkers and security put in one another.

“I’ve spoken with several advocates who say over-criminalization of victims, strict rules and safety concerns at shelters are often barriers to starting over in a safe place for many women,” said Grudberg. “Create a line of communication. Create a level of security and trust; once it happens, you create a dialogue. Once you build trust once, it becomes a conversation, living, breathing, that continues. Doesn't mean the fear goes away, but creating an entity and rapport [is vital],” said Grudberg.

Moving forward stronger

Service providers for domestic violence survivors like Downtown Women's Center and Jenesse Center advocate for their clients and navigate numerous challenges to house them. DWC has connected nearly 200 survivors with permanent housing services. The Jenesse Center provides wraparound housing services in an unprecedented mixed co-ed building they helped create.

Both Los Angeles centers offer therapy, employment and education services tailored to the needs of each survivor. For survivors like Lily, stability stemming from housing is transformative.

“It’s because of where I'm at. I am in a safe, comfortable zone with my pet,” Lily told AfroLA.

As a survivor herself, Grudberg sees the women in her care do so much more when they have access to permanent housing.

Grudberg said she’s inspired by the help she received when she left a relationship and a career in the military. She was with a man who had powerful connections in the military, and with his power of attorney had taken everything from her, she said. She was starting a new job, with no savings and nowhere to stay, after a forced abortion. She had been looking at houses with her friend, who began to worry for Grudberg when the realtor required first and last month’s deposit. The realtor stepped out and returned with the keys in hand, which she handed to Gruber.

“[The landlord] wants you to have a house. We aren’t gonna run the credit. Don't worry about the deposit,” the realtor told her.

She now uses her experience as a survivor to assist others who are in the position she was in. “That experience is what drives me. What do you need at the lowest of low?” Gruber said. “You need someone to advocate on your behalf, you need someone to say yes.”