How one reporter tied immigration rhetoric to losses in health coverage

An uninsured woman takes her children in for a medical check-up at a low-cost clinic in Colorado. (Photo by John Moore/Getty Images)

One woman who emigrated decades ago from the former Soviet republic of Georgia skipped chemotherapy for her multiple myeloma in 2017 out of fear that she might be deported.

Two other cancer patients who had overstayed visas were scared to seek legal status because they feared their relatives could face repercussions, according to an attorney for the New York Legal Assistance Group who assists patients in a hospital. As a result, the immigrants died without getting health care coverage that the organization believed they were qualified to receive.

Those were among the stories I heard as I reported on concerns from immigrant families that made them fearful of seeking health care. Across the country, undocumented and some legal immigrants have become more wary of visiting new doctors or signing up for government benefits because of ever-changing immigration rules under the Trump administration. I sought to explore this trend in part of my project, which was supported by the National Fellowship’s Fund for Journalism on Child Well-Being.

One of the biggest challenges I faced was in uncovering data to quantify the anecdotal stories I was hearing from doctors, other medical providers and lawyers. I sought a variety of information from every organization, government agency and expert I could think of but fell short either because data was not yet available or is not collected at all.

But then I thought about trying to get information through a request that would not answer all of my original questions but could still provide some insights. Even if I couldn’t prove that fewer immigrants nationwide were seeking medical care or signing up for government benefits overall, I might be able to show what was happening in a couple of areas.

Several states provide coverage for undocumented immigrants. So I decided to find out if the coverage for those groups was growing at the same rate as other Medicaid populations by filing open records requests in those states.

Drop in coverage

California’s Medicaid program, called Medi-Cal, had the most thorough statistics with information available at the county level as well as statewide.

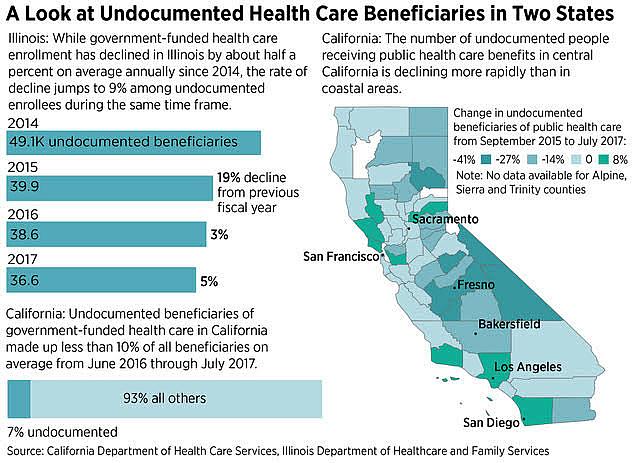

My calculations showed that from September 2015 until July 2017, the undocumented enrollment in Medicaid fell by about 4.4 percent statewide. The rest of the Medicaid population went in the opposite direction, growing by 2.7 percent. The biggest declines came after the latter half of 2016, when the presidential election’s rhetoric about immigration was heated and Donald Trump increasingly appeared to have a chance of winning.

I asked experts in the state why this might be happening.

There wasn’t a big exodus of people from the state to explain why Medicaid’s undocumented population was shrinking while overall enrollment was growing, they said. The experts also ruled out the possibility that large numbers of undocumented people experienced significant increases in income, making them no longer eligible for Medicaid.

Instead, they suggested political rhetoric and fear could be playing a significant role.

The coverage drop among undocumented people was particularly striking in conservative parts of the state.

Graphic: Sara Wise/CQ Roll Call

In Fresno County, undocumented enrollment fell by almost 33 percent from September 2015 to July 2017. The rest of the Medicaid population in that county grew by 6 percent.

Its smaller neighbor, Kings County, saw a 37 percent decline, while the rest of the county’s Medi-Cal population rose by 5.3 percent over that time frame. Other small counties saw drops of up to 41 percent in the undocumented Medicaid population.

Illinois also showed a steeper drop in the undocumented population than the rest of the Medicaid population. The number of undocumented beneficiaries fell by nearly 8.3 percent from fiscal 2015 to fiscal 2017, while the population of other groups fell by 2.6 percent over that time period.

Among those affected are children — including American-born citizens who are children of immigrants. We know that children’s health is affected by their parents’ coverage. When parents are uninsured, they also are less likely to sign up their children for benefits.

A December 2017 Kaiser Family Foundation brief cited two studies showing that a parent’s coverage in public programs is associated with higher enrollment of children.

Issues to watch

Immigrants’ access to health care will continue to be a big issue throughout the Trump administration and is worth exploring from different angles.

Information from the U.S. Census and other federal data is likely to later help us understand whether more foreign-born people nationwide went without health care benefits in 2017 and 2018.

Personally, I am continuing to watch to see whether the Trump administration will finalize a rule that has not been publicly released but could significantly impact legal immigrants’ health care coverage and ability to live in the United States.

Advocates who have shared a leaked copy of that rule say the proposal would redefine the term “public charge.” That term currently means someone who “is likely to become primarily dependent on the government for subsistence, as demonstrated by either the receipt of public cash assistance for income maintenance or institutionalization for long-term care at government expense,” according to the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services. Benefits received by one family member are not attributed to other family members unless the cash benefits amount to the sole support of the family.

But the Trump administration is said to be considering a broad expansion of the types of benefits that could count against legal immigrants and prevent them from living in the United States. The new definition could be interpreted to include some government health benefits, for instance.

This is worth watching. As policies change, reporters will want to talk to families who are affected as well as government officials on all levels, advocates, academics and others involved in implementation. I found families at local clinics and through community organizations, although it was very difficult to convince parents to allow me to use their full names because of the fear they were experiencing. I did convince a few to permit me to provide their identities and used one as an example, but their stories were not ideal for my story because they were less afraid of detection than others. Some people only granted me permission to use part of their names.

This story was one of the only times in my career that I reluctantly ended up using partial names. But it was understandable to me why families were reluctant to disclose their identities since the point of the story was to explain how some people are afraid of being deported or losing their legal permission to live in the country.

Continuing to track these issues is important. It’s easy to lose track of these types of policies, given how much is happening in Washington and around the nation. But these are issues that could affect families in a very direct way. Ultimately, if immigrants are more nervous about getting medical care, that could undermine not just their own health but also the public health of the nation.

Read Rebecca Adams' fellowship stories here.