L.A. clinic says immigrants scared to get care after ‘public charge’ controversy

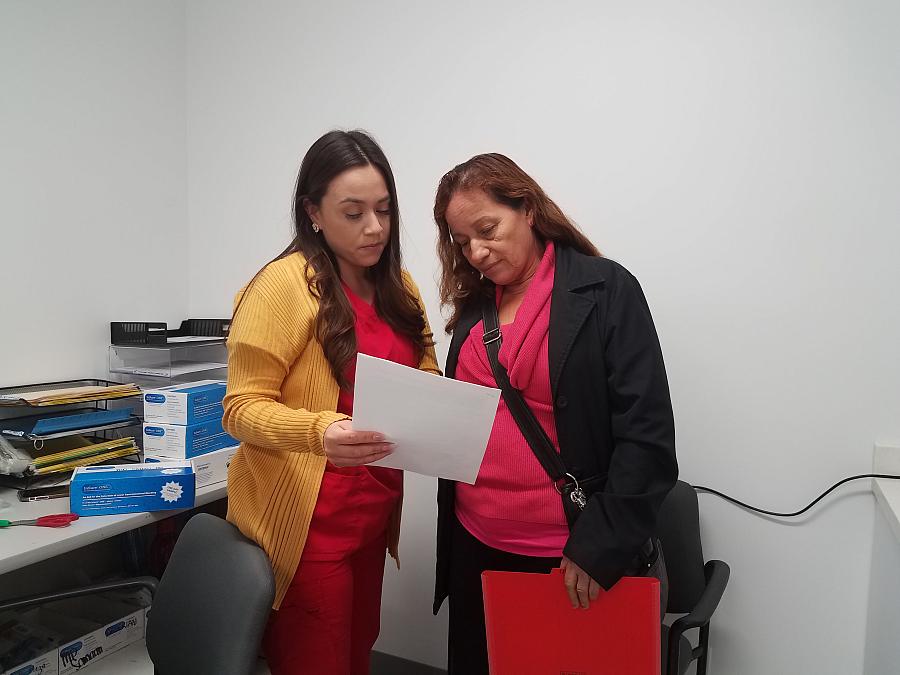

Medical assistant Deisy Hernandez discusses an upcoming appointment with patient Caya Mendoza, 62, inside Clínica Romero in Boyle Heights.

(Photo by Susan Abram)

The Salvadoran woman with a pallid complexion and labored breathing didn’t want to leave the community clinic.

She had come to Clínica Romero in Los Angeles’ Boyle Heights neighborhood because she felt weak after she was released from a nearby immigration detention center days before.

The ankle monitor issued to her by the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement tracked her every move. She felt safe inside Clínica Romero, one of two health centers that operate in predominantly Latino neighborhoods in Los Angeles. But she feared that if she left for specialty treatment anywhere else, even the massive public hospital just across the street from the clinic, she would be deported.

“When I told her she had to go to the emergency department for a blood transfusion, she kept saying ‘I don't want to go’,” said Deisy Mendoza, a physician's assistant at Clínica Romero who recalled the woman’s story. A blood test confirmed she was anemic, her hemoglobin levels dangerously low.

“She said, ‘Please, can’t you just give me something here’?” Mendoza said.

The woman’s plea is part of a broader problem, health providers say, in which both undocumented people and lawfully permanent residents have come to distrust public health care in the wake of the Trump Administration's aggressive stance on illegal immigration.

In September, the administration submitted a proposal to restrict the ability of lawfully present immigrants to obtain permanent residency if they’ve used public assistance programs. The proposed rule would expand the current definition of “public charge” to include nutrition programs, health care and other services legally available to immigrants.

Monday marks the end of the Department of Homeland Security’s 60-day public comment period for the proposed policy change.

Opposition to the rule has come from local governments and programs across the nation. But it was the city of Baltimore that filed a lawsuit in late November against the Trump Administration over the proposed ruling. The lawsuit, filed in the U.S. District Court of Maryland, argues that people who have used non-cash benefits — such as food stamps, nutritional programs for children or Medicaid — shouldn't fall under the public charge label.

The lawsuit also argues that strides made in public health and preventative care among undocumented immigrants and legal residents will be reversed if the policy changes.

“It's psychological warfare,” said Carlos Vaquerano, interim executive director at Clínica Romero, referring to Trump's proposal. “Obama deported more people than Trump, but what (Trump) is doing is pushing people out.”

The safety net clinic sees about 12,000 patients a year, but Vaquerano said those numbers have fallen in the past two years. The clinic, which opened 35 years ago, did not share any data to quantify the decline.

“The majority of Latinos have someone in their family affected by” the proposal to change the public charge policy, Vaquerano said. “I'm sure these policies are having an effect, not just in our clinic, but everywhere.”

A recent survey of providers by The Children’s Partnership reported a 42 percent increase in California parents skipping scheduled health care appointments for their children because of the political rhetoric surrounding immigration before the proposed changes in public charge rules.

The mere possibility of such a rule change has already had a chilling effect, said Adriane Casalotti, chief of government and public affairs for the National Association of County and City Health Officials.

“The impacts are really widespread when it comes to public and community health,” she said. “We're so focused on prevention — even a delay of a year can be a problem down the line.”

Casalotti said she’s already heard of immunization programs seeing fewer children due to misinformation. As she interprets the proposed rule change, immunizations don't count against someone seeking to become a U.S. resident.

“If the message is, ‘Don't use public programs,’ then that’s a huge issue for public health,” she added. “Similarly, kids who are U.S. citizens whose parents are not citizens are not getting services because they believe that could affect mom not getting in the country.”

At Clínica Romero, physician's assistant Mendoza said she still sees about 21 patients a day, but she's noticed that some haven't come in to help manage their diabetes since January, rather than once every three months. She said she also refers many people to mental health programs for anxiety and legal aid services for questions about eligibility for programs.

Patient Caya Mendoza, 62, said she is a legal resident who has come to Clínica Romero for 10 years for what she called “a knot of health issues.”

“Before, the waiting room was always full, but now it's not,” Mendoza said. “I'm not afraid. If something happens, it happens. But I know there are many people who are afraid.”