In LA, the rising wave of teen STDs is hitting segregated communities hard

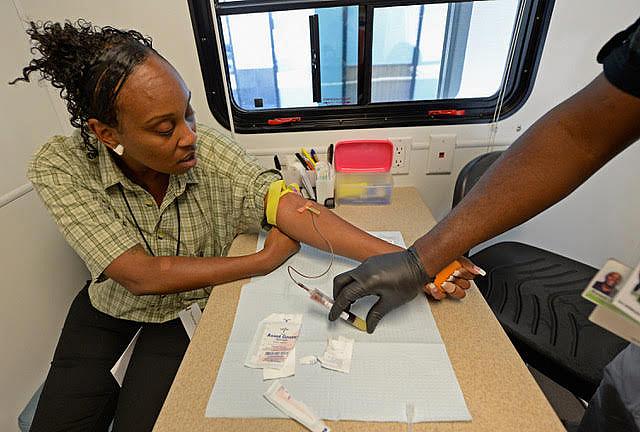

Testing for STDs and HIV/AIDS at a mobile unit in Los Angeles. (Kevork Djansezian/Getty Images)

“Larry gave me an STD?!” screamed Lakisha, my 14-year-old African-American patient in the pediatric clinic in South Los Angeles where I was practicing.

Lakisha, whose name has been changed, had just tested positive for chlamydia. Two days earlier at her routine physical, she disclosed that she was sexually active with a boy in her class. She called him the “love of her life.” That prompted me to screen for sexually transmitted diseases, or STDs. The Centers for Diseases Control and Prevention recommends testing sexually active adolescents and adults for chlamydia, gonorrhea, syphilis and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).

Lakisha’s case is part of a growing problem. STDs have been on the rise nationwide for the past five years. California had the highest number of reported cases (nearly 250,000) of chlamydia, gonorrhea, syphilis, and congenital syphilis of all 50 states in 2016, a ranking partly explained by the state’s large population. These STDs increased by nearly 40 percent from 2012 levels. Chlamydia cases were at the highest levels recorded since mandatory reporting began in 1990. Because many STDs go unrecognized and unreported, the true burden is likely underestimated.

In Los Angeles, STD rates vary widely with geography. South LA has some of the highest rates of STDs in the county. Chlamydia occurs in five out of every 1,000 people overall in the county, but African Americans have much highest rates of infection, especially young African American women. Their rate, 133 per 1,000 people, is more than five times higher than for young white females. Gonorrhea and syphilis rates are also higher among young African American women.

Racial disparities for STDs have persisted for decades. Nationwide, African Americans have significantly higher rates than other ethnic and racial groups. The degree of racial segregation seen in South LA only makes the problem worse. One consequence of segregation is that kids tend to date other kids within the same group in their neighborhood, facilitating the spread of STDs.

Young people are especially susceptible to STDs. Nationwide, nearly half of all new cases of STDs are among adolescents and adults, 15 to 24 years old. Biology also matters — adolescent female anatomy just happens to be more susceptible to infections. About 25 percent of sexually active teen girls have an STD. Teens are infamous for incorrect and inconsistent use of condoms.

We also know that teens' mental outlook matters quite a bit, since those who hold positive beliefs about their future are more likely to practice safer sexual behaviors. Researchers have shown that many young low-income black and Latino males in Los Angeles and Boston don’t anticipate a positive future. Often they fear for their safety and expect an early death. Low expectations for their future may contribute to riskier sexual behaviors, such as unprotected sex with multiple partners.

Untreated STDs in women can lead to long-term consequences, such as chronic pelvic pain, infertility and stillbirths. Infants exposed during pregnancy or at birth are at risk of blindness, deformities and long-term disabilities. Men who don’t receive treatment may not develop symptoms and continue to spread infections.

Public health officials have been working to find ways to curb the epidemic. Efforts have focused on education of health care providers about STD testing and treatment. Campaigns encourage everyone to talk openly about STDs, get tested and practice safer sex. In Los Angeles, the health department offers free condoms and school-based education programs targeting teens. But those efforts haven’t stopped the rising incidence of STDs in areas such as South LA.

Lakisha had many of the risk factors associated with acquiring an STD — she was a low-income, African-American teen girl who started having sex at an early age. And she lived in South LA, a segregated area with high rates of STDs. Lakisha received antibiotic treatment for chlamydia and urged her 14-year-old partner to seek treatment, which he did. But unfortunately, neither teen returned to my clinic for testing to be sure they were cured.

My experience as Lakisha’s doctor isn’t unique. My colleagues and I care for far too many adolescents and young adults who jeopardize their sexual health. We can offer treatment, pregnancy prevention and teach them about safer sex. I also try to help my patients learn a sense of control over their physical wellbeing and to visualize a promising future. However, there’s only so much we can do in the short amount of time they visit the clinic to combat the larger social forces in their lives that ultimately keep teens, like Lakisha, vulnerable to life-threatening infections.

**