Lessons learned examining addiction in Kentucky -- death, pain and too little help

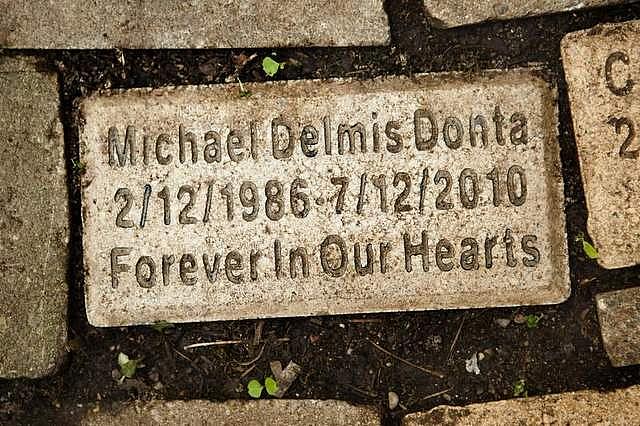

Over the past two years, I’ve spoken with dozens of Kentuckians battling prescription drug abuse. One woman attempted suicide while waiting for a bed at a treatment center. Another, whom I spoke with in the neonatal intensive-care unit of a local hospital, lamented being unable to stop using narcotics before giving birth to an addicted baby. And a man mourned the loss of his 24-year-old addicted son, who hanged himself in a motel room, leaving a baby son and pregnant girlfriend.

All of the stories broke my heart. But they needed to be told. Prescription drug abuse is epidemic in Kentucky, tearing apart thousands of families and taking the lives of about 1,000 residents a year. The Courier-Journal has made it a mission for the past two years to shine light on the problem, with the hope of inspiring change.

We had written several stories on the topic before I began my National Health Journalism Fellowship. But two areas that had gone unexplored until then were the problem of addicted babies and the issue of substance abuse treatment. Both were crucial to truly understanding prescription drug abuse and finding an effective solution.

Originally, I planned to include them in one large, several-day package. But then I spoke with a source in the Kentucky Office of Drug Control Policy, who mentioned that he had just gotten numbers from state epidemiologists showing the exploding numbers of hospitalizations for addicted babies in Kentucky. These were the first-ever numbers the state had crunched, and the news was shocking. The number of hospitalizations for Kentucky babies born addicted to drugs – primarily prescription pills – rose 2,400 percent in just over a decade, from 29 in 2000 to 730 in 2011.

My editors and I agreed that we needed to get something in the paper and on our web site quickly. Not only were we nervous that these numbers would somehow get out to other media, we also knew the public needed to know these shocking statistics about our most vulnerable citizens. So we decided to quickly finish writing and reporting the portion on addicted babies – and get it in the paper – in less than three weeks.

It was a very difficult proposition, to say the least. But with much scrambling, focus and overtime, we pulled it off. On Aug. 26, we ran a four-page special section on the topic and several accompanying videos on our web site.

The story not only detailed the numbers but also showed the human impact – babies who cry almost non-stop, sucking desperately on pacifiers to soothe themselves as they suffer through painful drug withdrawal. Such babies made up more than half the NICU population at Louisville’s safety-net hospital on one day. The stories also told the tales of their mothers’ struggles and the consequences of their addictions.

The story stirred immediate statewide and national interest, and swift reaction. The day after it ran, I was asked to (and did) appear on CNN to talk about the problem. I was also interviewed on the statewide PBS affiliate television station later in the week, and on Louisville’s NPR affiliate the following week.

In addition, I was asked to give a presentation on the stories before a Kentucky legislative oversight committee implementing a prescription drug abuse law our previous stories had helped inspire – a meeting also attended by dozens drug treatment professionals. And I was invited to speak at the Bartholomew Consolidated School Corporation's “Desperate Households” conference in early October in Indiana, which drew hundreds of educators, counselors, drug control officials and others.

Also, inspired by a past USC fellow, we reached out to community stakeholders to take our story further, which is something any reporter can do. Here are some of the results:

- The Kentucky Commonwealth’s Attorney’s office offered to send the stories to courts, jails and related places;

- An Appalachian anti-drug organization called Operation UNITE sent the stories to its hundreds of local and national contacts;

- The Kentucky Hospital Association sent it to hospitals across the state where deliveries take place, and to medical professionals in the obstetrics field.

After the stories ran, drug treatment professionals, parents and members of the general public contacted me to say how the stories had moved them. An official at Louisville’s main children’s hospital told the newspaper that they had so many inquiries from people wanting to volunteer with addicted babies that they had to start turning potential volunteers away.

While reaching out on these stories, I continued my reporting on the issue of substance abuse treatment, culminating in a three-day series that ran in December.

As I spoke with treatment professionals, recovering addicts, state officials and national experts, one thing became perfectly clear – there is far too little treatment in Kentucky, especially for the most hard-core addicts. That fact came through in interviews with dozens of people, and in our analysis of data from the U.S. Substance Abuse & Mental Health Services Administration treatment finder. This database can be very useful for journalists, showing treatment centers in each state and what type of care they provide. SAMHSA also has some very interesting statistics, by state, showing treatment admissions and types of care addicts are admitted into.

We mapped treatment centers throughout the state and found, among other things:

-Only 40 of 301 offer 24- hour residential care, and those are concentrated in just 19 of the state’s 120 counties.

-Nearly 80 percent are outpatient-only, mostly providing once-a-week care for an hour.

-Treatment shortages are most severe in Appalachian counties, which have the state’s highest prescription drug overdose rates. Six Kentucky counties that rank among the 10 highest for overdose deaths have just one outpatient center or no center at all.

In other words, there’s a whole lot of addiction and not nearly enough treatment, and the treatment that does exist is not available in the hardest-hit communities.

One challenge in these treatment stories was to balance these telling statistics with the human toll. From the addict’s perspective, too little treatment means months-long waiting lists, which are compounded by cost, distance and insurance barriers. I spoke with several addicts who said they called nearly every residential center in Kentucky only to be told there were no beds available to them. Many couldn’t stay clean without help, and continued to use drugs. One woman from a rural area had to wait 2 ½ months for a residential bed at a center in Louisville, two hours away. While she waited, she sank deeper into her addiction to prescription drugs and heroin, once accidentally overdosing on heroin and almost dying.

We discovered that state funding was also an important factor in the problem. Kentucky’s behavioral health budget for substance abuse treatment has remained stagnant for more than a decade, and the only area that has seen an increase in treatment funds is the Department of Corrections. Source after source told me that it was much easier to get treated for addiction if you commit a crime and get sent to prison.

I didn’t want to stop with uncovering the problem; I also wanted to show possible solutions. So I found a state with a better treatment system – Oregon. I visited that state, with the help of the fellowship funds, and found that they admit more than twice as many addicts to treatment as Kentucky does, have a well-coordinated system of getting people into treatment, and have a philosophy that treatment is worth the cost. They have increased substance abuse treatment funding despite the economic downturn, and also cover it under their Medicaid program, which our state, with a few small exceptions, does not.

Many Kentucky experts said our state has much to learn when it comes to treating the addicted. As Operation UNITE's Karen Kelly said, “If someone has cancer, you try to cure it. Addiction is no different. You need law enforcement, prevention and treatment. It’s a three-legged stool, and without all three legs, you fall over.”

I hope these stories will continue to inspire change in our community. After the stories on addicted babies ran, a legislator told me they were difficult to read because they were so heartbreaking. Readers have been voicing the same sentiment about the treatment stories. I tell them that the stories were even more difficult to report and write, since they were so full of pain.

But now that it's done, I can say that the past two years of reporting on this topic was well worth the effort and time and emotional toll. Why? Because the public and those in power need to understand this scourge in order to do something about it.

Photo Credit: Alton Strupp/Courier-Journal