UNSAFE: Abuse and neglect of Arizona's most vulnerable can happen anywhere

This story was supported by the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism's 2022 National Fellowship. It was reported by investigative journalist Amy Silverman, who began this project in 2019 while she was a ProPublica fellow at the Arizona Daily Star. She now is a producer at KJZZ in Phoenix.

Illustration by Theo Grace Quest

Throughout history, people with intellectual and developmental disabilities — including conditions like autism or Down syndrome — were regularly sent to live in institutions, away from family and society.

That began to change in the 1960s. And in 1999, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that people with IDD should live in the community whenever possible.

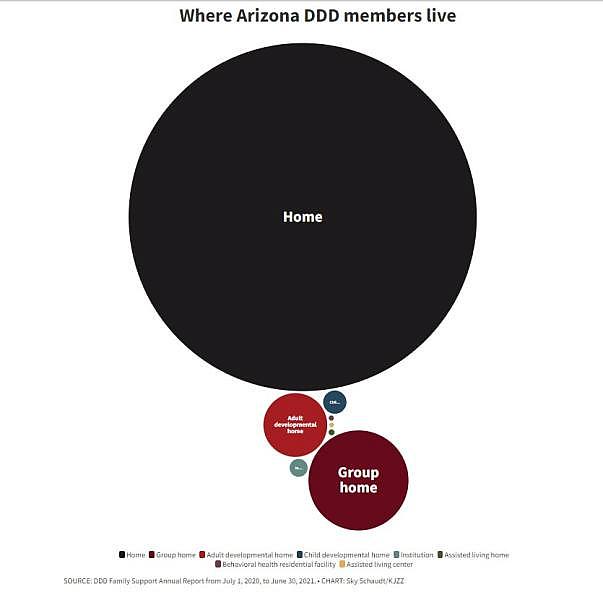

Today, fewer than 200 Arizonans with IDD live in an institution. The remaining 45,000 or so who receive caregiving services and other government benefits live on their own, with family or in small settings, like group homes.

But no matter where people with IDD live, they continue to be at risk. An investigation by KJZZ and the Arizona Daily Star found that physical and sexual abuse, as well as neglect, can occur anywhere — and often, nothing is done about it.

Hear Amy Silverman discuss the project with host Lauren Gilger on The Show

Part I: Blatant abuse

Mildred never thought her daughter would be a mother.

Then the phone rang on a Saturday morning. An unfamiliar woman identified herself as an employee at Hacienda HealthCare, the Phoenix facility where Mildred's daughter had lived since she was 2 years old.

"Oh, Mildred, I just wanna let you know, did you know you're a grandma?"

"I said, 'What are you talking about?'"

"And she said, 'Yeah, she had a baby boy.'"

Mildred remembers yelling, but almost four years later, she's not sure of exactly what she said. She does recall one thing very clearly.

"I threw my phone across the room."

+ + + + +Days later, on New Year's Eve 2018, news broke that a woman with profound intellectual disabilities had given birth at a long term care facility.

Within weeks, an employee was arrested and charged with sexual assault. He's now in prison. Mildred and her family have settled lawsuits against Hacienda HealthCare and the state.

But things will never be settled for Mildred.

On a warm day in fall 2022, the older woman sits in the conference room of her lawyer's north Phoenix office. KJZZ News and the Arizona Daily Star are using her first name only, to protect her privacy. This is the first time she's spoken to a journalist.

Mildred wears a blue T-shirt and jeans, her salt and pepper hair held back by a sparkly headband. Her eyes fill with tears as she talks about her daughter, the fourth of seven children.

The girl had her first seizure when she was 2 weeks old. Mildred knew something was wrong, but she didn't know what to call it.

"I would be going to her, taking her to her appointments, and tried to explain to the doctors, the nurses, what she was doing, turning blue, shaking, her eyes rolling up," she said.

Mildred and her family live in the San Carlos Apache Indian community, several hours from any big health care facilities. Eventually, the family was sent to Phoenix, where the little girl had a seizure in front of a doctor, who was then able to diagnose her.

"I kept her home as long as I could," Mildred said. "But then she started developing respiratory problems."

The doctors convinced Mildred and her husband to put the girl in a state-funded care facility in Phoenix called Hacienda HealthCare. She was just 2 years old. Mildred describes it as the "hardest day of my life."

"I was reassured that she'll be taken care of, they'll care for her. And I did say that to them, you know, I cared for her as much as I could at home. So now you take care of her."

The girl grew up at Hacienda. Mildred was happy with her daughter's care. She kept a close eye on her when she visited, checking for sores, bruises, even ear wax. She and her husband requested that their daughter never be left alone with a male caregiver.

The family visited on Christmas Eve 2018. Mildred noticed her daughter's feet were swollen. She mentioned it to the staff. She called the next day and was told the younger woman was scheduled to see a doctor.

"And that was it. I never got a call back saying why her feet were swollen until the 29th."

Her grandson's birthday.

Mildred rushed to Phoenix.

"That's where that part of our life changed."

Her daughter was recovering in the hospital. The little boy was nearby.

At first, Mildred wasn't sure even wanted to see the infant. She prayed about it, then went to the intensive care unit, where the baby was being weaned off of his mother's seizure medications.

"He was just laying there all small, facing the other way, we just saw the back of his head. And we saw him, talked to him in Apache, apologized to him for how he came, but told him that he's ours. I said, He's going home with us. He's mine. This is my flesh and blood. No matter how he came, he's my flesh and blood."

Mildred pulls out her phone to show photos of a beautiful, healthy child with big eyes and dark hair. He loves spicy food. He's always surrounded by family.

"He calls all of us mama. Me, my older daughter, the aunties."

From his youngest days, Mildred has brought the boy along to visit his mother, who now lives in another care facility in Phoenix. He calls her mama, too.

Mildred worries about the day her grandson finds out about his father.

"Every day, every morning, every time I look at him."

+ + + + +In the months following the Hacienda HealthCare incident, advocates called for reform in Arizona facilities that care for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities, or IDD.

But the reality is that there are fewer than 200 Arizonans with IDD living in institutional settings. Another 45,000 live in the community – with family, on their own, or in small group home settings. They qualify for health care, job training, recreational programs and caregiving services.

No matter where they live, Arizonans with IDD are not safe — not according to reports collected by the state, which document everything from a scratch to a rape. An analysis by KJZZ and the Arizona Daily Star of more than 10,000 "incident reports" made to the Arizona Division of Developmental Disabilities in 2019 and 2020 revealed thousands of charges of neglect and hundreds of serious physical and sexual abuse allegations. Often, there's no resolution to these complaints.

Among the incident reports is one documenting the birth of a full-term baby boy to a 29-year-old woman with a seizure disorder and needs so significant she cannot walk, talk or care for herself in any way. She does respond to sound and light, making it even harder to consider that she was likely raped multiple times by a man caring for her.

Whether in an institution charged with providing constant oversight or out in the world, bad things are happening to some of the state's most vulnerable residents. Family members, advocates, medical personnel — just about anyone close to people with IDD already knows this. But it took the rape at Hacienda HealthCare to get the world's attention.

Even that hasn't resulted in much change. A task force examined the problem for years, a few laws were passed, some funding was increased. But almost four years later, a public education campaign still hasn't been put in place. It's almost impossible to find detailed information about a potential living setting for a loved one. Family members and guardians are kept in the dark about even the most basic information, something Mildred said happened to her many times.

Her best advice to other families: "Ask questions."

"Ask questions, just basically, How she's doing? What is she doing today," Mildred said. "Asking how they are as a human being."

+ + + + +Today, Mildred's daughter lives in a state-run facility in Phoenix. It's smaller than Hacienda, tucked into an inner city neighborhood.

She really likes quiet, her mom says.

"When we're there, we're loud," Mildred said, laughing. But it's important to her that her daughter be with her people and around her family's traditions.

"I sing to her in Apache, and I told the supervisor there at the home to play her some traditional music," she said. She bought her daughter a fancy television set and asked the staff to put in Wi-Fi.

"So they play the YouTube and they get that traditional music going on, even the crown dancing, what we do."

Earlier this year, Mildred's daughter came home for a visit. Mildred and her husband, Joe, had been chosen as godparents for a young woman in the community, and there was a big celebration. The older woman's eyes shine as she recalls sending a traditional dress for her daughter to wear.

By the time the van made it to the reservation, the ceremony was over.

"So she couldn't hear any of the music, but she was home with us and we were just all happy. Family just gathered around the van and want to take a peek at her. And she was kind of like dozing off."

The family was together. They took pictures. Mildred's daughter was never taken from the van.

"I told them, 'I don't want her getting off.' It was dusty that day. I don't want her getting sick, you know? So she stayed like maybe for two hours, and they took her home, and we were just all waving at the van," she said.

"She made it home to us."

Part II: 10,000 incidents

Illustration by Theo Grace Quest

Hear Amy Silverman and Sam Burdette talk about the data

An analysis of more than 10,000 incident reports collected by the state of Arizona in 2019 and 2020 reveal hundreds of claims of sexual and physical abuse of people with intellectual and developmental disabilities — and thousands of instances of alleged neglect.

The Arizona Daily Star and KJZZ spent a year examining the data, obtained through a public records request. Although the reports were sometimes heavily redacted or incomplete, they painted a picture of desperation among caregivers, family members and — most importantly — people with intellectual and developmental disabilities, often referred to as IDD.

The main takeaway: Abuse can take place anywhere, and the perpetrator can be anyone.

In Arizona, about 45,000 people with IDD receive services from the state. They are referred to as "members."

Experts caution that most instances of abuse and neglect aren’t documented in the first place. The U.S. Inspector General found in a 2021 study that 99% of incidents in group homes were never reported.

Arizona officials would not comment on any specifics.

In a statement, a spokesperson for the state wrote:

“The DES Division of Developmental Disabilities (DDD) is committed to ensuring the health and safety of its members, and the quality of their care. DDD’s process is to review all reported incidents and investigate those that are quality of care concerns through its Quality Management Unit. DDD also works with providers to remediate identified issues. Health and Safety visits are conducted by clinical quality management staff for reports of abuse, neglect or any situation that indicates a potential for harm to the members in a residential setting (however, if an incident occurs in a member’s own home, DDD staff would report to DES Adult Protective Services or the Department of Child Safety as required). Appropriate measures are taken to ensure the health and safety of a member.”

Among the incident reports were allegations of neglect, including people with IDD missing medication doses, living in filthy conditions and being ignored by caregivers. In one neglect case, a person with IDD went from weighing 130 pounds to 73 pounds in a six-month time period.

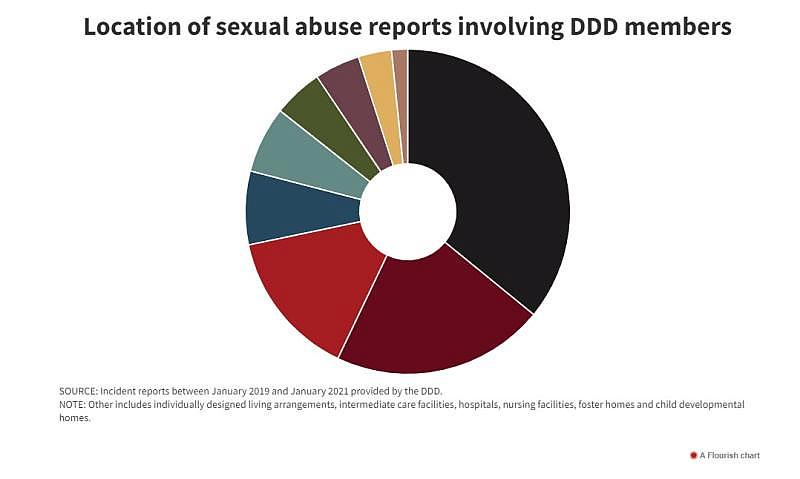

Reports of sexual abuse ranged from inappropriate comments to allegations of rape.

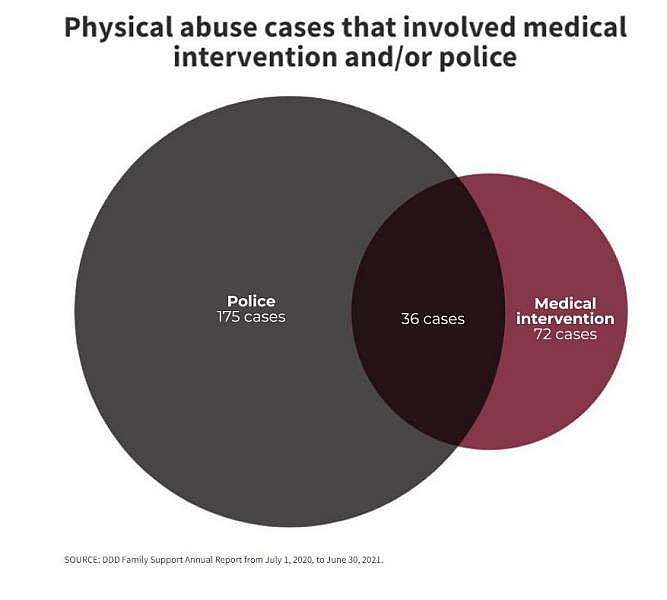

And there were hundreds of claims of physical abuse serious enough that police officers had to get involved and/or medical care was required. Among them:

- A state-paid caregiver pushed a person with disabilities head first into a fish tank after an argument over a TV remote control.

- The stepfather of a person with disabilities was arrested for sexual abuse after the member said, "dad," "ouch," "hurt," "no."

- A person with IDD showed up to school, obviously having been beat up. When the mother tried to call the group home, no one answered. The group home didn’t report the incident or speak with DDD staff till after the mother reported the incident. The staff member was terminated.

Those claims were substantiated. Many more were not — or had not yet been closed at the time the records request was fulfilled.

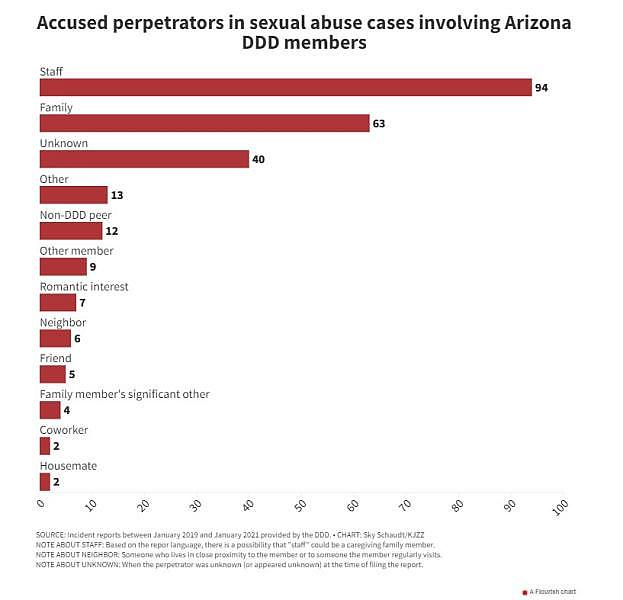

According to the data, the perpetrator can be anyone — a medical professional, a teacher, therapist, friend or neighbor.

"You know, I wish I could say there's a category of person that we have to really watch out for, and then we would know what to watch out for. But it's pretty much everybody," said Nora Baladerian, a California-based clinical psychologist and creator of the Disability Without Abuse Project.

"I like to say that service providers, including psychologists, psychiatrists, counselors, of course would never, ever abuse a child or an adult with a disability. But I can't actually say that and do it with a straight face."

More than a third of the sex-abuse allegations involved a family member. From one report: "Mother kept lifting member’s gown while two staff were in the room and she was referring to his penis as his 'little animal,' and she kept stating that she was afraid something was going to happen to his 'little animal.'" She also was caught touching and/or cleaning his genitals and saying, "You better tell me you love me or I am going to spank you."

And while abuse can take place in just about any setting, group home employees account for about half the physical abuse allegations, and a fifth of the sexual abuse claims — even though only about 4,000 of the state’s 45,000 DDD members live in such settings.

Baladerian tells the story of a friend of hers whose sister has an intellectual disability. She’s non verbal and lives in a care facility. She had been acting different, kind of cranky, withdrawn — but Baladerian’s friend didn’t know why.

"One day she was on the freeway, and the hospital called and said, 'Hey, we got some lab results back from some of the tests that we did on your sister. And, um, she has gonorrhea,' and my friend just about drove off the freeway."

But even a sexually transmitted disease wasn’t enough to substantiate some reports of alleged abuse in Arizona.

One DDD member was diagnosed with herpes. She’d never been diagnosed with it before, and staff couldn't figure out how or when she contracted the virus. Police closed the case due to lack of evidence.

Another DDD member was treated for gonorrhea and chlamydia. That case was also closed due to lack of evidence, although there was suspicion of "an unknown female that 'touched' the member, and the member refuses to discuss the incident."

Allegations of sexual abuse involve everyone from classmates to friends to neighbors.

"While member was doing yard work at his in-law’s house, he went with an adult male neighbor to his home and had unprotected sexual intercourse with a woman in her 30s while two adult males and two adult females watched and/or participated."

Sometimes, it’s another person with IDD.

In one instance, a DDD member stated a man exposed himself to her and made her perform oral sex on him. The two were separated and the man was later arrested. Charges were dismissed because the man was determined to be "incompetent," which is legal speak for being unable to participate in one’s own defense.

If nothing else, these reports offered a glimpse into a world that is typically closed to outsiders:

- A DDD member and staff got into an argument. Staff hit the member with a backpack and called the member a "bitch." Staff verbally threatened the member, went to her car to get a baseball bat and brought it into the group home. Another staffer intervened; the member was not hit with the bat. The staff member was terminated.

- In attempting to get a DDD member to eat breakfast, a group home employee asked, "Are you gonna act like a cry baby today? You're 51 years old, for Christ sake." The member covered his face and began to cry. Staff yanked the member's coloring book out of his hand and used his palm to push the member's forehead back. Later, staff pushed the member's head back with force when giving medication and called the member "a little sh--." The member was later found shaking and was taken to urgent care. He was discharged with "no concerns."

- A caregiver at a day program convinced a DDD member to send them nude pictures, then threatened the member using the photos. The caregiver posted the images to the day program's website and to Facebook, and also shared them with friends.

- A DDD member informed his mother that three staff members had taken him to the restroom and touched their genitals in front of him. An investigation revealed the member was displaying more sexually oriented behavior in the weeks leading up to the alleged incident. The member had been smelling chairs where female employees recently sat, claiming he could smell their underwear. The member also would randomly say "vagina" and "penis." A detective reported that information provided to the police department was vague and said the case was officially closed. The investigation concluded that no incident ever occurred.

Again and again, families interviewed for this series said they have been unable to get copies of incident reports involving their loved ones.

And then there are the people with IDD who don’t have family members looking out for them.

Sam Burdette analyzed the data for this story. Jill Ryan and Sarah Trim contributed to this story.

▮ ▮ ▮ ▮

Next on UNSAFE

Part III: Unaccountable

The abuse of a 4-year-old boy with IDD was caught on camera, and his caregiver made an admission to police. Yet, the case is among hundreds of allegations of physical and sexual abuse that could not be proved. Airing Nov. 30, 2022

Part IV: Sex ed and IDD

People with intellectual and developmental disabilities can be left out of the conversation when it comes to sexual agency and expression. A pilot program of Special Olympics Arizona helps athletes with IDD to navigate healthy relationships. Airing Dec. 1, 2022

Part V: What next?

It’s been four years since a woman was raped at Hacienda HealthCare. Despite efforts at reform, critics say the state of Arizona is not doing nearly enough to protect people with IDD from abuse. Airing Dec. 2, 2022

ABOUT THIS PROJECT

This series was supported by the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism. It was reported by investigative journalist Amy Silverman, who began this project in 2019 while she was a Pro Publica fellow at the Arizona Daily Star. She now is a producer at KJZZ in Phoenix.

- Reporting: Amy Silverman is a journalist, teacher and memoir writer in her hometown, Phoenix. She's executive producer of KJZZ's original production, The Show. Silverman's work often focuses on people with intellectual and developmental disabilities, inspired by her daughter, Sophie, who is 19 and has Down syndrome. UNSAFE continues the work she began in 2020 through a partnership with the Arizona Daily Star and ProPublica’s Local Reporting Network.

- Editing: Lindsey C. Riley is a senior editor at KJZZ. She joined the station in June 2022 after more than two decades of reporting and editing for print/digital news media in Phoenix.

- Digital production: Sky Schaudt is a senior digital editor at KJZZ who has spent more than 15 years working with reporters and editors to create engaging experiences for online audiences.

- Audio production: Nate Boyle is a journalist from Chandler, Arizona. He’s an assistant producer of KJZZ’s original production, The Show. Boyle is an alumni of the Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication at Arizona State University and specializes in audio storytelling.

- Data analysis: Sam Burdette is a recent master's graduate from the University of Arizona's School of Journalism and investigative freelancer contracted with KJZZ. Burdette's career focus is on data, investigative journalism and breaking news, with an emphasis in watchdog journalism fueled by her belief in the importance of transparency within governing bodies.

- Additional reporting: Jill Ryan is a producer and journalist at KJZZ. She has a master’s degree in investigative journalism, and is a faculty associate at the Walter Cronkite School of Journalism at Arizona State University. Her investigative work often includes deep dives into governmental systems that are failing the people they’re intended to protect. Sarah Trim is a college student in Tempe.

- Illustrations: Theo Grace Quest is a queer, nonbinary graphic designer and illustrator. Quest also serves on the organizing team for Phx Zine Fest. Their work strives to form connections over the human experience (the good, the bad, the weird, the lonely) and to create and celebrate accessibility to the arts.

[This article was originally published by KJZZ.]