Medify for Journalists: How a startup could help add context to your reporting

What do algorithms that comb the web to predict future airline ticket prices have to do with health?

If you ask Derek Streat, those kinds of algorithms--ones that read and process language--can have a big impact on patients' ability to get informed.

Farecast changed a lot about how we book flights online, and Streat hopes that his latest company, Medify, will do the same for how we make decisions about our health. Streat is CEO and co-founder with former Farecast vice president of technology Jay Bartot. Most of Medify's development team, about half the company, also came from Farecast. Medify, as Streat explains it, makes health data from medical studies useful for patients by extracting and combining critical data about patients and outcomes.

Zina Moukheiber, who writes the Healthworks blog at Forbes, posted in September about her experience with Medify when it had just entered public beta. She tested the site by looking up Alzheimer's disease and found some surprising data-based findings about treatment options.

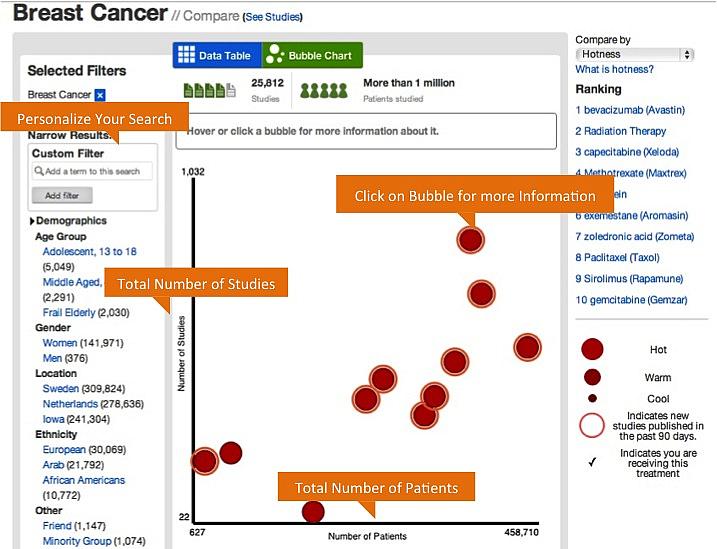

Medify today returns treatments ranked on "hotness" (how new they are), strength of evidence and efficacy (how well they work). You can also dig into the individual studies and get to the original data. (

Moukheiber was excited about the implications of a site like this for journalists. After meeting Streat at SXSW Interactive in Austin two weeks ago, I am too.

Medify was selected as a finalist in SXSW Accelerator, a fierce competition for startups to get time centerstage and be dubbed "the next big thing" by judges and the audience. While the implications for patients are fascinating, I saw Medify as an efficient tool for the media. Journalists are starved for context when they report on the latest study. If you trust that Medify's algorithms are leading you in the right direction, this kind of search is a really efficient way to both add context and get at meaningful source material.

The algorithms comb through public data including Medline (which many health journalists access via PubMed) and Food and Drug Administration data -- all those package inserts chock full of information about trials and studies that are stored as text files on the FDA website. Streat says that Medify also uses the Unified Medical Language System to help with taxonomy. The algorithms of the site depend on these kinds of medical dictionaries to find synonyms and generic names for branded drugs, for example. The company plans to add data from ClinicalTrials.gov later this year.

"What we find is that even for professional users -- doctors, pharmacists and students -- it's a way to understand things a lot of faster than Medline or PubMed," Streat explains. The site provides contextual data to help you figure out if the study you're covering is an outlier or consistent with other studies on the disease or treatment.

Journalists should keep in mind that the company's plans to generate revenue includes selling aggregate and de-identified data about users – what people look up and the kinds of questions they are asking -- and licensing the platform to hospitals and pharmaceutical companies who want to build communities for their patients. While all data collection will be permission-based, Streat says, "we do think there's opportunity for individuals to raise their hand and say, 'I want to share more about what I'm doing because I want to be in your next trial.'"

He also maintains that earning money in these ways will not compromise the integrity of the database or algorithms: "We have a commitment in the company to always let the data speak. We will never as a company alter the prostate cancer section of the site, for example, to focus on the therapies provided by our partners who are paying us," Streat explains.

Journalists who use Medify to find new studies should know that the site is updated very quickly, but not necessarily in real-time. Streat says that data is "ingested" daily, so there could be, at most, a 24-hour delay for a new study in Medline to appear in Medify.

The site is still in beta, but Streat says it's ready for primetime. They stay in beta, like so many tech start-ups, mostly to show that they are improving.

"It's a work in process. It's not perfect -- medicine itself isn't perfect. We're open to feedback and change," Streat says.