Opioid deaths are soaring. Why is it so tough for people to get medication to treat addiction?

Opioid manufacturers, distributors and pharmacies have started to distribute the more than $50 billion in settlement funds they’ve agreed to pay for their role in the opioid epidemic. While most of the settlements require states to spend the majority of these funds on addiction treatment and prevention, there is little agreement on what that means.

At the same time, overdose deaths, driven largely by fentanyl, continue to rise.

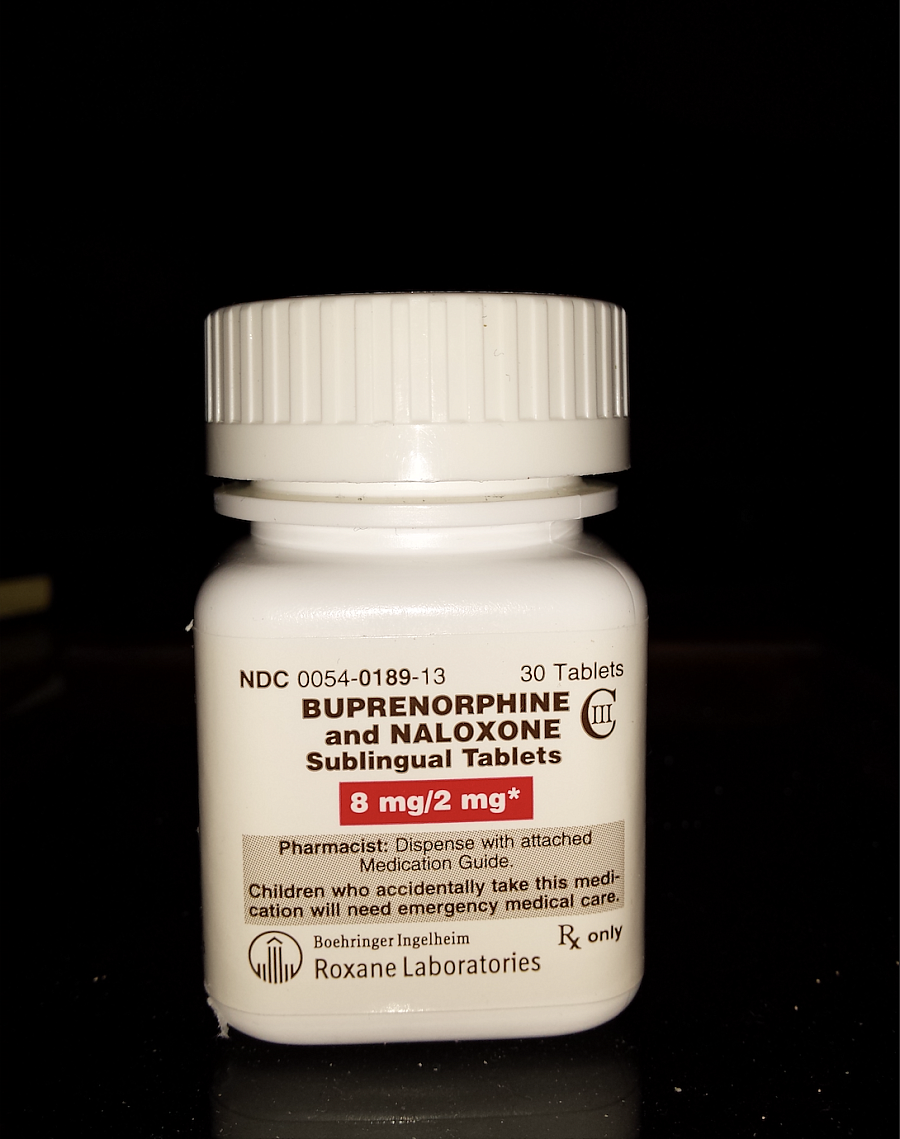

Experts say that, in the face of this grave public health crisis, expanding access to FDA-approved medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD), such as methadone and buprenorphine, should be a top funding and policy priority. Both are synthetic opioids that reduce withdrawal symptoms and cravings.

These medications are highly effective in treating opioid addiction. Both have been shown to substantially reduce risk of overdose, decrease transmission of diseases like Hepatitis C, and improve the overall well-being and stability of people in recovery. Many patients feel they are nothing short of life-saving.

Yet these medications remain strictly regulated and, for the more than 2 million Americans estimated to have opioid use disorder, difficult to get.

The barriers to accessing treatment remain so high that researchers estimate only about 11 percent of Americans who need these medications can get them. More than 70 percent of residential treatment centers in the United States do not offer MOUD. And 80 percent of U.S. counties don't have a single certified Opioid Treatment Program, the only setting where patients can legally access methadone.

“Opioid addiction is actually highly treatable,” one expert told me. “But most people don’t have access to that treatment.”

The federal government has recently moved to relax some rules around MOUD, for example by making buprenorphine easier to prescribe. Bipartisan bills introduced in Congress would allow patients to get methadone at their local pharmacy with a prescription from a physician who specializes in addiction.

At the same time, the federal Drug Enforcement Administration recently proposed rolling back changes that expanded access to buprenorphine through telemedicine, prompting backlash from patients and providers. Resistance remains at the local level, too: some of the states hardest hit by the opioid epidemic have the most restrictive policies around MOUD, and some providers have been slow to enact new flexibilities granted by the federal government.

Another expert put it to me this way: In the age of fentanyl, this just doesn’t make any sense.

The barriers that prevent patients from getting this treatment are myriad, and are higher for low-income patients, patients of color and people living in rural communities. Accessing methadone, for example, almost always requires a daily visit to a clinic — a journey that can strain household budgets and disrupt patients’ ability to work and spend time with loved ones.

But the barriers aren’t just regulatory. Another is stigma. Many patients report feeling criminalized or shamed when they seek care. And many policymakers and health care providers remain resistant to the idea of using these medications to treat addiction, even though they are widely considered to be the gold-standard for treatment.

Regardless of what the barrier is, experts say that each creates consequences for patients that not only have the potential to disrupt their recovery, but also increase their risk of overdose.

This year, as a USC Center for Health Journalism 2023 National Fellow, I’ll be reporting a series of stories that unpack the obstacles to accessing MOUD and reveal the human cost of those obstacles: to patients, their families and their communities. I’ll dig into the historical roots of the strict government rules around medications like methadone and show how these regulations have contributed to inequities across class, race and geography. I also hope to highlight programs that work and explore the policy debate over expanding access to MOUD.

My reporting will focus on communities that have been hardest hit by the opioid epidemic, and on states that have the tightest restrictions. Key to my reporting will be sources with lived experience: people who use MOUD, the providers who care for them, and the researchers, activists and policymakers who are working to narrow this access gap.