Panel dissects forces driving hospital consolidation, offers ideas on what might be done

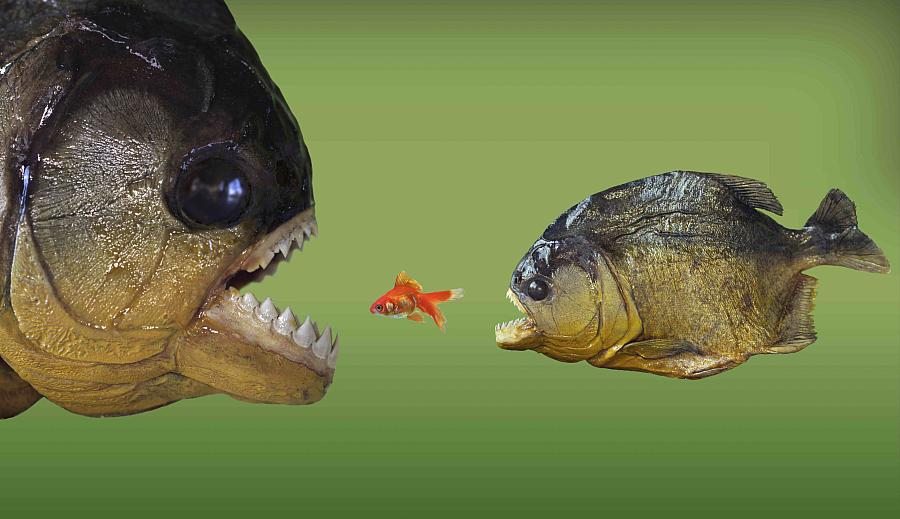

Since the Affordable Care Act’s passage five years ago, more and more hospitals have swallowed up smaller rivals and purchased doctors’ practices. These emerging health care giants have more negotiating power with insurers, which can result in higher premiums that threaten the very cost savings the ACA promised. That changing health care market, its effects on health costs, and steps that might curtail consolidation were at the heart of this week’s Reporting on Health webinar, “Supersized: The Rise of the Hospital Giants.”

The May 19 webinar featured Paul B. Ginsburg, a University of Southern California professor who is an expert on health care markets, and reporter Margot Sanger-Katz, who covers health care for The New York Times’ The Upshot. The discussion also included slides and resources from Martin Gaynor, a professor of economics and health policy at Carnegie Mellon University who is widely known for his work on hospital consolidation.

Sanger-Katz presented data showing how the trend of hospital mergers has accelerated since the passage of the ACA:

But the precise role of health reform in fueling these changes is still unclear, since many of the catalysts — such as new payment models — were already gaining traction in the private sector before the ACA became law in 2010.

“The law itself … is basically agnostic,” Sanger-Katz said. “It doesn’t say that bigger hospitals are better than smaller ones. But there are a lot of things about the world of health policy that are changing, both because of the ACA but also because of other recent health policy changes.”

She cited multiple factors that could be contributing to consolidation, including the 2009 HITECH Act, which encourages health systems and physicians to use electronic health records.

“You hear a lot from hospitals saying that buying, implementing and running these records is actually a pretty big burden and it can be harder for small organizations to do it,” Sanger-Katz said.

Health reform has also spurred the creation of more Accountable Care Organizations, where health providers and hospitals work together to coordinate patient care and share in any cost savings. Those financial incentives encourage hospitals to employ all the players who take care of patients — including physician groups — so they can better coordinate care and share data, Sanger-Katz explained.

The ACA also reduced payments for hospitals caring for the uninsured, known as disproportionate share hospital payments or DSH funding. Those reductions could further squeeze some hospitals financially and make a merger more attractive.

“Government payments are declining for hospitals and they’re just kind of feeling the pinch,” she said.

On top of that, the new “doc fix” bill passed in April changes the way Medicare will pay doctors, with reimbursements tied more to the quality of care rather than volume of care, as with “fee-for-service” payment systems.

“We may see some doctors feeling this is too much pressure — they can’t manage these kinds of metrics and they want to be part of a larger organization,” Sanger-Katz said.

On top of those tangible policy changes, there are psychological aspects driving hospitals toward mergers as well, including what she called “musical chairs anxiety.”

“There’s worried if they wait too long there won’t be a good partner for them, or they’ll be the only ones standing and they won’t be able to compete,” she said.

On the physician side, a new generation of providers just out of residency may be less interested in running their own business and prefer the schedule and stability of a salaried position. And, doctors often get reimbursed higher for work in a hospital compared to an outpatient setting, which means being part of a larger system could lead to higher payments. (Sanger-Katz pointed to the examples of cardiology and oncology, where reimbursements are typically higher in a hospital setting).

[Check out the full presentation HERE.]

For health journalists, all of these factors are ripe for coverage. Take a look at which specialties are remaining independent and which ones and more likely to merge, she suggested. Journalists could also look into charity care and evaluate how much hospitals are delivering before and after consolidation takes place in a given market. Another idea to look into is whether mega-hospitals are trying to be insurance companies and whether they’re capable of making that difficult transition.

To research mergers in your area, Sanger-Katz suggested taking a look at groups that track mergers such as the American Hospital Association; Irving Levin Associates; the Advisory Board Company; and the Medical Group Management Association. Financial documents such as hospitals’ form 990 returns are helpful, while for-profits file forms with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. Some states have all-payer claims databases that can help quantify cost changes for health services, and a number of crowdsourcing sites attempt to provide the same.

Competing forces

There are some theoretical benefits of consolidation, such as better-coordinated care in larger systems and reductions in costly, duplicated procedures. But, so far, there’s little on-the-ground evidence of those advantages. What is clear is that prices tend to go up while quality is often unchanged or declines when competing hospitals or provider groups are removed from a market.

When hospitals purchase physician practices, it can create barriers for patients looking to access the best care, since those doctors may be more likely to steer patients to more costly services at their affiliated hospitals, Ginsburg said.

But there are competing forces in play that could mitigate some of the consolidation fears, Ginsburg said.

More online consumer price-shopping tools that allow patients to compare prices on procedures could help direct consumers to lower-cost providers, though there’s been disappointing progress with these so far. For patients who are hospitalized, there are often few incentives to price shop since they’ll likely meet their deductible or out-of-pocket maximums for a hospital stay.

Creating more limited networks, which restrict what doctors and hospitals patients on a given insurance plan can visit, could be another way to encourage lower prices. In these networks, consumers trade cost savings for less provider choice. Exchange plans are an ideal place to use this approach since insurers are freed from the one-size-fits-all plan model that is typically employed for workplace insurance, Ginsburg said.

For this approach to work, though, there’s a need for more accessible information on which providers are in one’s network – a major vulnerability with exchange plans so far, and their out-of-date directories. (The White House recently announced plans to require insurers to keep their directories accurate and up-to-date.)

Ginsburg said he also expects tiered-provider networks will be increasingly popular, since they allow more patient choice while maintaining lower costs. Under these plans, patients can choose to pay more to see a specific provider or less to see a different one.

Another force that could counteract physician-hospital mergers is the growth of all-physician organizations, which can slow the movement of doctors to hospitals. And patient centered medical homes, where primary care physicians join with others to coordinate care and control spending, could also slow the movement of physicians to hospitals, according to Ginsburg.

Ginsburg’s perspective is that the American health care system needs to keep making strides toward better care coordination so that we “get the very high potential long term benefit in better care and more efficient care and address the consolidation through other policies rather than just not have additional consolidation. I think there are additional opportunities for market approaches to offset the impact of growing provider consolidation and leverage.”