For powerful series on deep health disparities in South’s Black Belt, a reporter marries data, history and moving life stories

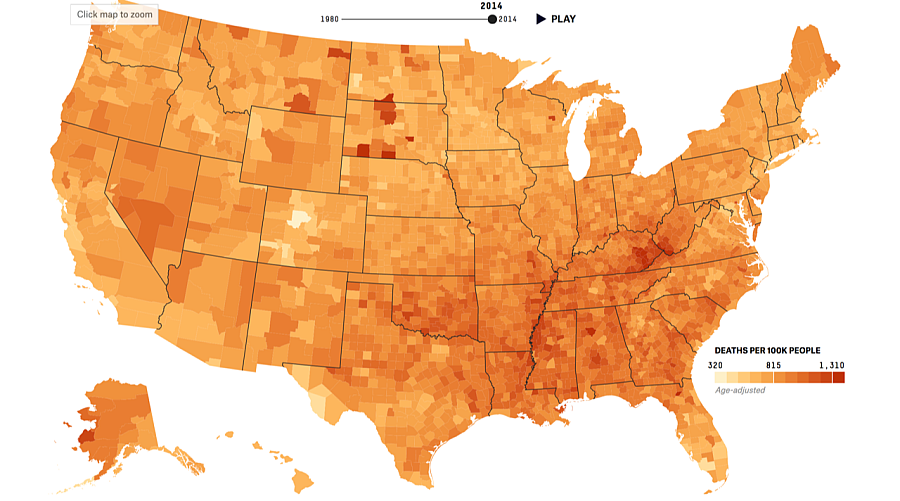

Credit: 538/Ella Koeze

When I met Dr. Remona Peterson at a Starbucks in Tuscaloosa, I’d already spent several weeks talking to dozens of people around the Alabama Black Belt. I’d met with state officials, community leaders, farmers, and doctors, among other groups. People had shared their life histories and medical concerns with me, in an effort to help me understand a place that is at once the origin of much U.S. wealth and home to the most persistent poverty in the country.

“The Black Belt is just so much in need,” Dr. Peterson said. It’s hard to overstate how dire that need is. Hospitals are closing at a rapid rate, chronic diseases like diabetes are rampant, as are treatable and preventable illnesses like tuberculosis and cervical cancer. And underlying it all are deep economic and racial inequalities that stem back more than 150 years to the foundations of slavery. “I don’t want to be looked at … as though people are dumb,” she continued. “Some people just need opportunity. Like me, I needed that opportunity. Someone just gotta give us a chance.”

I went into my fellowship series, which examined health disparities in the heart of rural, Black America, armed with a lot of data and a lot of history. But it was the many guides like Dr. Peterson who were able to explain what those statistics say about life in the Southern Black Belt today.

Over three stories, FiveThirtyEight explored issues surrounding persistently poor health outcomes in the region. The first story in the series used historical and contemporary maps and data to illustrate connections between slavery and present-day health outcomes. A second story looked at how rural health challenges are particularly acute in the Black Belt. The story drew on data showing the tiny number of African-Americans from the area who go on to medical school, the challenges outsiders have providing quality health care to people in the Black Belt, and the financial strains on local providers to explain why access to health care is limited for many area residents. A third story will cover some of the ways that systematic racism throughout U.S. history impacts health in the region today.

Because these issues are systematic, there’s no obvious person or group to point fingers at. That’s one of the reasons it’s so challenging to write about what public health experts refer to as the social determinants of health — the problem is everywhere and related to everything.

Here are a few things we learned in reporting this series about how to help readers connect with systemic problems:

It’s important to know both the power and limitations of reporting on data. Data brought us to this series. After looking at myriad data sets on health outcomes for positive and negative outliers, we realized that state and county borders, the most frequent geographical breakdowns for health indicators, obscured important patterns linking racism and health outcomes in the U.S. That led us to pursue an exploration of what we know about how these health disparities came to be, and what can be done about them.

But it was important to remember what data can’t tell us. While the growing study of the social determinants of health has found creative ways to measure racism, which has both biological and psychological consequences, and has begun teasing out how exactly racism impacts health, the field is still young. We know that disparities exist, and there is solid evidence about the negative health impacts of racism. But it can also be an insidious, and therefore challenging, thing to measure or quantify. And, despite the longstanding health disparities, there is limited research on the Black Belt. That made it all the more important to combine data and narrative storytelling for the series.

A good interactive can be the story aide that keeps on aiding: One of the most striking things in researching this project was seeing the variety of contemporary U.S. maps that mirror an 1860 map of slavery. That included modern day patterns of mortality. My colleague Ella Koeze created an interactive showing patterns of mortality by cause of death, which we included in two of the series’ stories to show the outsized risk of dying from things like diabetes, HIV, or cervical cancer in Black Belt counties. The interactive was made using a large and fairly new data set from the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington. It added a powerful layer of information to this series, but we have also used it in several other stories since. That includes a look at changes in life expectancy, a story examining why some of the healthiest counties in the U.S. have some of the most expensive health insurance, and coverage of new research showing that while heart disease is declining in most places, it is on the rise in some communities. We think it’s particularly powerful that these stories were authored by multiple people. A lot of time and effort went into making the interactive, but it has been an asset to the whole website and staff.

Positive outliers can be a powerful connecting point. For a story on the challenges of delivering health care in the Black Belt, we focused on the complicated path Remona Peterson took to becoming a doctor. Dr. Peterson grew up in the Alabama Black Belt, and is currently one of only a few physicians working in the area who also grew up there. She is tenacious, funny, intelligent, warm, and a motivated and accomplished student. And yet, it was extremely challenging for her to get through medical school. Her experience helped to illustrate the many economic and social barriers African-Americans who are interested in medicine currently face.

And yet, she found a way. Dr. Peterson was quick to point out that it took a lot of people a lot of work for her to become a doctor, and the arrangement that made it possible was very unique. Rural Greene County Hospital, which had struggled to recruit doctors, particularly ones that understood the local community, helped Peterson pay for school in exchange for a commitment to work at the rural hospital when she graduated. Multiple reporters and hospital administrators, people with deep and intimate knowledge of rural staff shortages and hospital closures in the South, wrote to say that they hadn’t heard about an arrangement like Dr. Peterson’s before.

An outsider’s perspective doesn’t have to be a hindrance. When I set out to report this story, I was acutely aware that I would be an outsider reporting on complicated, entrenched, and sensitive issues. No amount of time or reporting could make me a member of the community, or allow me an insider’s perspective on multigenerational, institutional racism and the associated power dynamics that are so influential on health outcomes. That meant that to report this story, I needed to find people willing to talk and share with me, and really listening to what they had to say. I searched out community leaders — not just political leaders, but the connectors who know everyone and have their ears to the ground. That led me to incredible people like Mrs. Ethel Giles, an organizer and community activist. She introduced me to dozens of people in the small town where she lives who generously shared stories about their childhoods, professional careers and health histories. There was also Rev. Christopher Spencer, who works in community development at the University of Alabama, is a reverend at a church in a rural Black Belt community, and also grew up in the area.

Though not all of the people I met made it into the final stories, collectively, they painted a picture for me of what’s changed and what hasn’t in their communities over the last half century. They also told me about the networks that they lean on for support, and the ongoing challenges confronting the community. Coverage of the Black Belt is often confined to local papers, but we found great value in bringing these issues to a national audience. Disparities so deep and so longstanding don’t often make the front page, yet they are foundational to understanding contemporary politics and policy.

Read Anna Maria Barry-Jester’s fellowship stories on health disparities in the South’s Black Belt here.