Reflections on my fellowship project

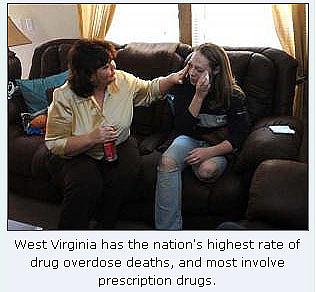

When I set out to produce my fellowship series on prescription drug abuse in West Virginia, I already knew some grim statistics.

Residents here are more likely than those of any other state to die of a prescription overdose. Because of high rates of chronic disease and occupational injuries, people in West Virginia also fill more prescriptions per capita than anywhere else – 19 prescriptions a year compared to a national average of 12. It's easy for drug abusers to get their hands on pills.

Finding people to illustrate these numbers was difficult, but not as hard as I feared it would be. Some people wanted to talk about the issue. They knew it would help others. Of course, it took a lot of phone calls to locate the right people for interviews.

I found recovering addicts through a local rehab program. I found a mother who had lost her son to a drug overdose because I knew a relative of hers through my beat at the newspaper. Other sources included a county prosecutor, doctors, a local pharmacy professor and treatment counselors. Community groups that work to prevent drug abuse were very helpful in my search.

It was hard to narrow down my focus on a topic as complex as this one. I recommend that other reporters outline each topic in their series as soon as possible when working on a project like this.

Another challenge was getting statistics from the Drug Enforcement Administration. The agency keeps record of the amount of controlled substances consumed in every state. While the DEA used to post these reports on its website, records for the past few years were not available. I made repeated requests for the information. I had hoped to get data for every state so that I could compare West Virginia's consumption of prescription drugs to other states'. Eventually, the agency gave me its most recent data, but only for West Virginia. This showed some staggering trends – like the fact that the state's per capita consumption of the painkiller fentanyl has jumped nearly 350 percent in the past decade.

DEA officials told me they are working to make nationwide data more accessible. I hope the information will soon be available for other reporters.

When the series was published, I got calls from doctors, police officers, state lawmakers, and people whose relatives have struggled with addiction. They were grateful that the newspaper brought attention to the issue. I also got calls from people who suffer from chronic pain. They felt that highlighting drug abuse was unfair to people who legitimately use painkillers. This is what makes fighting prescription drug abuse so challenging for the medical community – many people need the medicines that are abused by others. I tried to illustrate that complexity in my series.

Since finishing my project, I have continued to cover the issue of prescription drug abuse for my newspaper. In February, national drug-policy chief Gil Kerlikowske visited West Virginia as part of a tour through Appalachia focusing on prescription drug abuse. The U.S. Attorney's office in Charleston and Sen. Jay Rockefeller hosted forums on the topic, too.

I am also following developments in Florida, where newly elected Gov. Rick Scott nixed his state's plan to develop a prescription drug monitoring program. His decision has upset police and lawmakers in West Virginia and other states. Police here say the program would have helped curb what's called the "Oxy Express" or the "Flamingo Express" – the trafficking of prescription drugs from Florida, where pain clinic regulations are notoriously lax.

I am grateful for the opportunity to participate in the fellowship program because it brought attention to the damage that prescription drug abuse has caused in my state. I hope that continued public interest in the issue will help make a dent in this huge problem.