Revisiting Michigan's most devastating environmental disaster

I had been a news reporter for WZZM in Grand Rapids, Michigan for nearly seven years before I ever heard of the state’s most devastating environmental disaster – the worst agricultural disaster in U.S. history.

Nearly 40 years ago, due to human error, cattle feed was mixed with the flame retardant chemical called PBB instead of being mixed with a nutritional supplement. The feed was then fed for approximately two years to cattle, pigs and chickens all over the state before animal illnesses and birth defects triggered an investigation. After researchers confirmed that the animal feed was tainted, more than 30,000 cows, 1.5 million chickens and thousands of pigs were rounded up and killed. Unfortunately, by then approximately 90 percent of Michigan residents had consumed contaminated dairy or meat.

How did this disaster affect their long-term health? I found that since 1973, researchers at the Michigan Department of Community Health (MDCH) and later, Emory University, have been trying to answer that question. Tracking a representative sample of farm families, they found a disproportionate increase in breast cancer and thyroid disease as well as infertility in women and early puberty in girls. Emory University began assisting the MDCH in 1998, and after the health department lost its funding for the project, Emory obtained a federal grant to take over the project from MDCH and continue the research that would no longer be funded by the state of Michigan. The problem was that the Michigan community health department could not hand over the participants’ personal information because of HIPPA laws protecting patient privacy. So Emory University began holding community meetings throughout the state in hopes of continuing the research and perhaps attracting still more participants who were affected by the disaster.

Once I learned of the struggle to continue the research, I knew two things: I needed to bring this story out of the shadows to help recruit those affected to participate in the ongoing study, and I would need far more than the traditional two minutes allotted for most of my television stories. I had one significant advantage in my reporting: the story was heavily archived and documented. Prior to attending the July 2012 California Endowment Health Journalism Fellowship conference, I was able to secure much of the needed background information and interviews. I unearthed old news footage at my news station and discovered a documentary called “Cattlegate” that contained additional footage. I also spoke with the MDCH and convinced one of the original health investigators who worked on the research to talk with me.

In addition, I cast a wide net with friends and colleagues who had grown up in Michigan. As it turned out, a co-worker’s family had eaten the tainted food and he himself had been part of the original study. He attended several community meetings held by Emory University (which I was barred from attending) and brought back contact names and phone numbers for me each time. It was through this process and searching newspaper archives that I was able to track down several key characters, along with affected families.

But although public documents on the disaster were plentiful, not all of them had been analyzed or reported. The hardest part was confirming whether each affected farm family had received a settlement, and if so, the amount each family had received. It was a question that anyone watching the documentary would have, and I wanted to answer it.

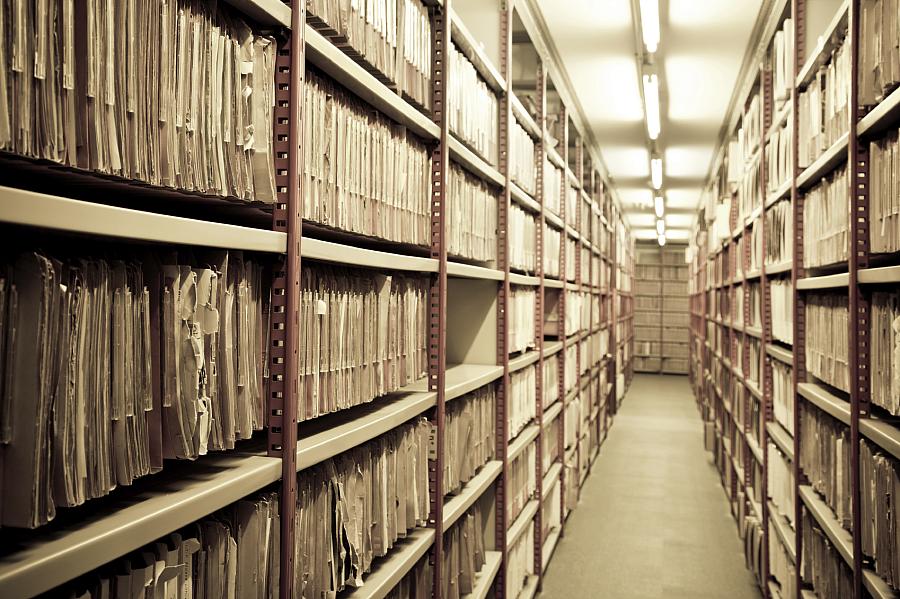

The state of Michigan was more than willing to share this information; I was pleasantly surprised to find out. The now decades-old documents were in the United States Bankruptcy Court archives in Chicago. All in all, there were 137 boxes from the nearly 20-year-long court case. It took two and a half days on the phone with multiple people and an additional $150 to get the figures I felt I needed for the end of the documentary, but it was well worth it.

Of course, one of the central challenges was figuring out how to put a human face on a heavily archived story. No matter how rich the documentation, without people this broadcast story would have had little impact. Getting people from a decades-old story to talk on camera was one of my most difficult challenges, not the least because the cost of filming them was almost prohibitively expensive.

My first obstacle came in securing a freelance photographer. While my news director agreed to give me as much support as he could, our small staff would not be able to handle dedicating a photographer to this project. A good freelance photographer would have cost me $1,500-2,000 a day, and I needed at least two days of shooting and a week of editing. I had to be resourceful. I reached out to a friend at another station who graciously agreed to commit to the project for a more modest fee.

With that task behind me, I began to schedule interviews. They were set until about a week before the shoot, when two people backed out because they just didn’t want to relive what they had gone through. My mistake was perhaps not fully understanding the depth to which the affected people felt used and forgotten. My advice to other reporters doing this kind of project is to prep people as fully as you can and make sure you have more interview subjects that you need. This is because once you arrive at the site, your interview subject may change his or her mind. Television cameras can be very intimidating, and sometimes no amount of reassurance will change their mind once they’ve decided they no longer want to be interviewed.

Our first shoot lasted 13 hours and required driving half the state of Michigan. Our second day of shooting was a little shorter, at just eight hours. With the hardest part done, I had to set the fellowship project aside for a month. The November television ratings were coming up and I would have to commit to my full-time health reporting job for the next 30 days. After ratings were over I was able to log and write my piece, pick out the music and graphics, and work with the photographer to edit the piece via FTP. It may seem like stating the obvious, but documentaries are a team project and it is crucial to build supportive relationships with your colleagues. I am lucky to have such a wonderful friend, who is also an amazing photographer and editor. Without him this project would not have been possible.

Our documentary, “Tainted Michigan: 40 Years of PBB Contamination,” aired on December 29, 2012. In addition, I organized a public viewing through social media, inviting members of the community, health agencies and friends to watch the documentary in a closed venue. It garnered so much attention that even the original lawyer for Michigan Chemical, the plant responsible for the PBB contamination, attended the viewing. I regarded that as a compliment, though he took issue with the final dollar amount that the farmers were awarded. He said it was more, but he smiled and said “job well done” when I reminded him the number he quoted was for the environmental cleanup.

On March 19th 2013 WZZM re-aired “Tainted Michigan” at 7 p.m. All the feedback I received from viewers was positive, most of them thanking me for bringing the story back into the spotlight. Most gratifying, many wanted information on how to enroll in the study with Emory University. This made me feel that I had accomplished the most important goal of my fellowship project – to bring awareness to a devastating agricultural disaster that is still undermining the health of many Michigan residents 40 years later.

Image via iStockphoto.com