Severe weather disasters, health & structural racism: A critical intersection

Photo by Spencer Platt/Getty Images

Not long after we watched in horror as racially charged violence erupted in Charlottesville, Virginia, our nation braced for and is now recovering from Hurricanes Harvey and Irma. Those hurricanes, like other severe weather events, are significant in their effect on individuals and their health. These events impact the very fabric of communities, destroying not only physical infrastructure but also disrupting the social factors that impact our health. Restoring the physical infrastructure and returning these individuals and their families to healthy communities is a major undertaking that stresses the very resilience of our society. Returning underserved individuals and their families to communities in the same state in which they left is a failure to recognize the inequities that existed before the disaster occurred and perpetuates the conditions that initially created these underserved communities.

At the core of the challenges these communities face, and a major factor that is often not talked about openly that explains the baseline state of these communities before the disaster hit, is structural racism. Tragically, racism still exists in our communities and remains a major problem in our society. Whether it is the overt hate and racial animosity that we saw in the protests and recent violence in Charlottesville, the racially driven police brutality we have seen over the years in communities of color, or the structural racism we see that results in underserved communities being more at risk during disasters, the results to our health are the same; a higher morbidity and mortality. The people living in these underserved communities are aware of these inequities and do complain about them, but they are generally unable to muster the political and economic will to affect change. This is a core reason for the toxic stress that affects the health of community residents. Higher levels of blood pressure, obesity, and violence are clinical effects of this chronic stress.

The challenges for disaster victims living in underserved communities had their start long before the most recent severe storms hit, and long before the violent protest in Charlottesville. Such challenges start with policies and actions that lead to discriminatory and inequitable social and economic conditions and our society’s stance that it is acceptable for them to occur in the first place. Protesters carrying swastikas and shouting words of hate are disturbing. But the construction of a community environment that discriminates in a way that puts people at increased risk for poorer health and a shorter life expectancy is equally troubling and must be addressed.

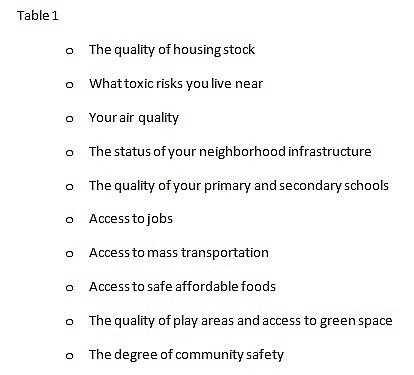

Most of what influences your health occurs outside the health provider’s office and goes beyond your genetic makeup. They are the social conditions that exist such as your physical environment, toxic exposures and health-impacting behaviors like smoking or physical inactivity. We call these the social determinants of health, and their influence is enormous. In addition, where you live matters; ZIP code has a profound impact on the health status of individuals and communities as it determines a range of social factors from the quality of the housing stock to the degree of safety in a community (See Table 1).

Interestingly, where you live is often determined by a series of structured factors based on income and societal influences that have historically been driven by racism and social segregation policies. Underserved communities have a degree of resilience that has allowed them to survive under extremely adverse conditions on a day-to-day basis. However, the infrastructure and personal losses that occur with a major climate event overwhelm this inherent resilience, exposing the inequity in its starkest terms. Climate-influenced disasters like Hurricanes Katrina, Sandy, Harvey and Irma; droughts; and wildfires are where the inequity of underserved people and communities become most apparent. In all of these events, the exposure risk to negative environmental conditions was higher and the ability of these people and communities to return to normal is significantly impaired. As we learned during Hurricane Katrina and its recovery, the wealthiest people recovered more quickly than the poorest. In addition, the health impact to these individuals was significant, resulting in a worsening of their health. The political and economic barriers that existed in these communities before the storm, while becoming more transparent to the public, did not lessen and in many cases became stronger.

Examples of what needs to be addressed include the location of manufacturing plants — with increased risks of environmental exposures — in underserved communities; unequal access to infrastructure repairs during normal times that are worse after a disaster; and ensuring adequate financing to support recovery efforts. The goal should be to achieve true equity in recovery, which may require additional investment and must take into account how they are rebuilt to address the structural inequities that initially put them at risk. At the American Public Health Association, creating health equity is one of our core values. That sounds like a lofty goal. Yet, it is possible if we do the important work of addressing structural inequities as well as the ways racism itself affects health. Overt violent acts like we saw in Charlottesville force us to have a truthful and open dialogue about racism and its impacts. Structural racism must also force a similar conservation. Talking about racism is an important first step. Changing the landscape so racism becomes unacceptable in our society is a public health priority.