Experts Say Child Welfare System Reform Needed To Better Serve Black Children

The story was originally published by the The Observer with support from our 2025 Child Welfare Impact Reporting Fund.

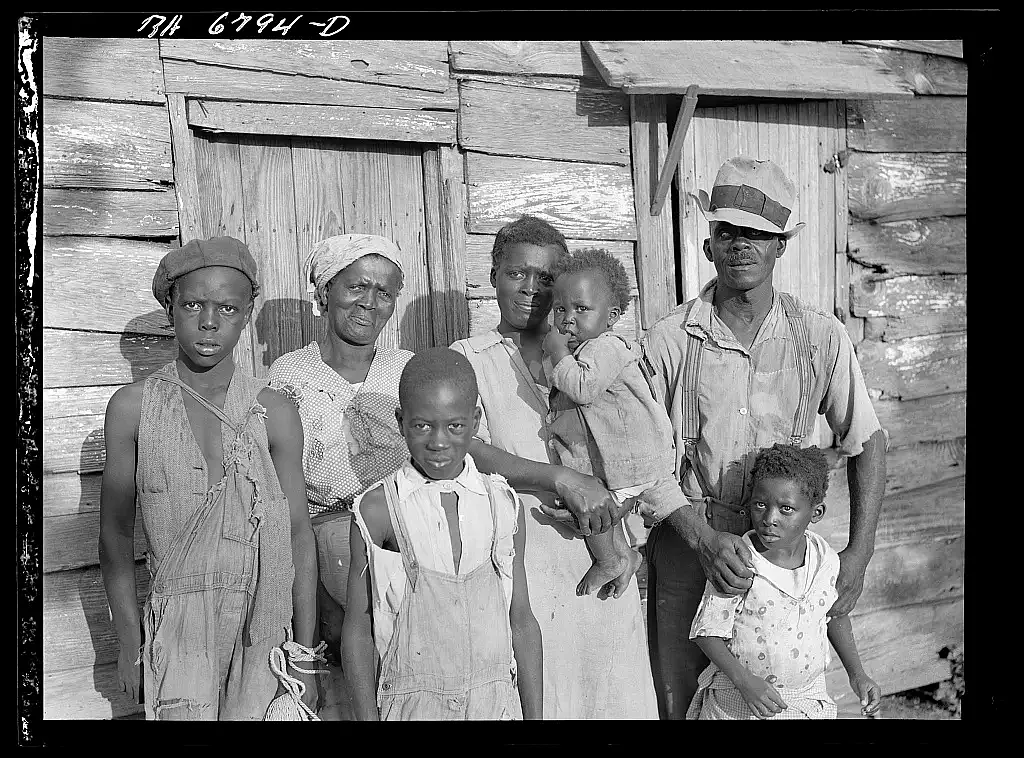

The historical context of the child welfare system, marked by racial bias and systemic inequities, significantly impacts its present-day operations and the experiences of Black children and families. Understanding this history, including the parallels between justifications used for slavery and those in the modern system, is crucial.

Photo courtesy Library of Congress

There is a deep-seated distrust of the child welfare system within the Black community, stemming from a history of racial bias and systemic inequities. The fear of children being “snatched up” by “the system” and placed in the control of strangers is all too real.

Black parents are more likely to have Child Protective Services (CPS) called on them. Black children are more likely to be removed from their homes and tend to spend more time in foster care. Socioeconomic factors and race play a significant role in these disparities.

Experts say understanding and addressing the historical context of the child welfare system is crucial to creating a more equitable, culturally competent, and supportive system that best serves children, particularly those disproportionately affected by past and present injustices.

“The system is not set up for us,” says Essence Graves, a longtime social worker.

Graves worked at the state and county levels, including 15 years with Sacramento CPS before the promise of better pay and a smaller caseload prompted a departure for Solano County.

The primary goal is to make services more sensitive to the needs and culture of black families, not to question the fundamental conflict between the child welfare system and the integrity of the Black family and community. Child protection authorities are taking custody of Black children at alarming rates, and in doing so, they are dismantling social networks that are critical to Black community welfare.

Dorothy Roberts, “Torn Apart: How the Child Welfare System Destroys Black Families”

The common perception of the system within the Black community is one of negativity, Graves says, often characterized by the image of a white woman arriving to condemn their parenting and then driving away with their children.

While Black children make up 14% of the U.S. youth population, they constitute 23% of children in foster care. The overrepresentation of Black children in foster care isn’t a new phenomenon.

“We’ve come a long way from framing the issue as one of simple disproportionality,” says Shereen A. White, a former juvenile justice attorney who serves as director of advocacy and policy for Children’s Rights. “It’s time for solutions.”

White and the New York-based organization’s policy work focus on racial inequities in child welfare, particularly how structural racism drives the overrepresentation of Black children in the system.

“We don’t want a proportionate amount of children in the system based on their existence in the population,” White continues. “We know how harmful and traumatic the system is in terms of the history and how we got here. The child welfare system really evolved from historical practices of family separation and assimilation of non-white people.”

During U.S. slavery, Black males were forced to produce children as workers, and Black children often were sold or gifted away from their parents, resulting in lasting effects on the Black community. Most never saw their families again. The fallout from government-sanctioned separation has had lasting effects on the Black community.

Six Degrees Of Separation

Between 1854 and 1929, the orphan train movement, an extension of earlier “child-saving” efforts, relocated poor and homeless children. The Children’s Aid Society transported children by train from overcrowded East Coast cities to the West. The primary focus was the offspring of poor European immigrants. Black children often were deemed unworthy of such efforts. Eerily similar to slave auctions, children were displayed for public viewing. Prospective “saviors,” including some farmers, would inspect them, occasionally requiring them to perform physical tasks to assess their suitability for work. Contracts were signed between the Children’s Aid Society and the people who took the children. The Black children who were transported often faced racism and discrimination in their new homes and communities.

“There has always been this notion in our country that some parents are not deserving of their children,” White says. “For Black people, that goes back to enslavement, when Black families were separated often, when separation was profitable for slaveholders and a tool of oppression and control. This idea that Black people were not worthy enough to take care of their children shows up throughout history and is reflected in our nation’s policies and systems and is very much at the root of the child welfare system.

“In the early years there were a lot of religious organizations who were engaging in this process of helping some families, but not others. There was a time when Black people weren’t even allowed to receive services for the needs that they had, and it wasn’t until the mid-1900s when more and more Black children were allowed to receive services for basically their parents living in poverty and not having what they needed,” White continues.

In a paper, titled “Legally Sanctioned Takings of Black Children: How Slavery Reverberates in the Modern Child Welfare System,” Chicago-based public defender Abigail Mitchell draws parallels between the justifications used for slavery in the late antebellum period and the language used in the modern family-policing system.

“The modern institution utilizes the same antebellum paternalism justification used during slavery to cast enslavers as ‘well-intentioned’ and the enslaved as ‘in need of their guidance,’” writes Mitchell in the piece published by St. Mary’s School of Law’s “Law Review on Race and Social Justice” in 2024. “Throughout the history of the United States, the White American ruling class has aided in carrying out the implementation and enforcement of policies and regulations which lead to countless family separations,” she continues.

Those Poor Babies

The Federal Children’s Bureau, the agency that oversees child welfare for all states, was formed in 1912.

“In some of their formation documents that we found, they talk about the idea that children could not be happy growing up in a poor home, that poor families can’t take care of these children. That was a basis for creating this system of family separation. You see those same attitudes really resonate today. A lot of judges and family courts believe that if you’re poor, you shouldn’t have your children, you can’t take care of your children,” White says.

“This idea is baked into definitions of neglect that allow people who lack financial resources to experience family separation simply because they don’t have money. That notion was baked into the foundations of this system.”

Prior to the Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act of 1974, the main focus and function was on keeping children safe from physical and sexual abuse. The legislation added a category for neglect. This game changer resulted in more children being separated from their families.

“There’s so much in the history of our social service programs in the U.S. and how they have worked to basically ensure that Black families are unable to provide for themselves and their families and living in poverty generation after generation,” White says. “Most families who become involved with the system are also dealing with poverty. That begs the question of why we have poverty in our country and who is experiencing it.”

Shocks To The System

Government-sanctioned separation has had lasting effects on the Black community. Impoverished Black families have historically been judged by different standards, leading to disproportionality in the child welfare system.

Photo courtesy Library of Congress

Sociologist Dorothy Roberts believes that the system largely punishes Black families and refers to it instead as a “family policing system.” Roberts is the author of “Shattered Bonds: The Color of Child Welfare” and “Torn Apart: How the Child Welfare System Destroys Black Families and How Abolition Can Build a Safer World.”

Critics like Roberts and White argue that “child welfare system” is a misnomer.

“When people call it the child welfare system, you’re sort of reiterating this notion that it’s helping children, that it’s a benevolent and good system for young people and the reality is, it’s not,” White says.

Using the term “family policing system” helps point out the parallels between the criminal legal system and child welfare system, she adds.

“People can wrap their heads around the deeply embedded racism and harm of the criminal legal system, but they’re less able to see how that is embedded in the child welfare system,” she continues.

One doesn’t have to search far into the past to find disturbing accounts of how children involved in the system can fare. In March, a white West Virginia couple was sentenced collectively to up to 375 years in prison after being convicted of adopting five Black children and using them as slaves on their farm. The couple was convicted of more than a dozen charges, including human trafficking, civil rights violations, use of a minor child in forced labor, and child neglect.

In a 2018 murder-suicide, two white women drugged their six adopted children, all of whom were Black, and drove them off a cliff in Mendocino County. Journalist Roxanna Asgarian chronicled the children’s lives and their loved ones’ failed attempts to navigate the system in her book, “We Were Once a Family: A Story of Love, Death and Child Removal in America.”

Response Time

Members of the National Association of Black Social Workers (NABSW) will discuss the system’s impact during this month’s 57th annual conference in Virginia. Former NABSW President Toni Oliver will lead a workshop, “Tracking the History of the Child Welfare System: Its Role in Breaking Up and Controlling Black Families,” and explore legislation, policies, and practices that have worked to police, control, and separate Black families.

Closer to home, Parents in Training Inc. hosts its first California Adoption, Trauma and Healing Conference in November at UC Davis. The conference aims to reach adoptive families and child care professionals. Speakers will include Parents in Training Executive Clinical Director Bryan Post, a former foster youth and adoptee who is now a clinician and expert in child behavior and adoption; and former California Surgeon General Dr. Nadine Burke Harris, a leading expert on childhood trauma and its long-term effects on health. Dr. Burke Harris previously chaired First 5 California. First 5’s chief deputy director, Dr. Angelo A. Williams, continues Dr. Burke Harris’ objectives centered on adverse childhood experiences, or ACES, and toxic stress response. The goal, Dr. Williams says, is to ensure safe, stable, nurturing, trauma-informed and healing-centered environments for all children.

First 5 California performs outreach to system-impacted families and engages state agencies to support them.

“Our mission is systems change,” Dr. Williams says. “That’s exactly what we’re supposed to be doing.”

Coloring Outside The Lines

Dr. Williams says that reconstruction is necessary to change current systemic issues. He points to Native American children being placed in boarding schools in the 1800s and 1900s that were bent on teaching them to assimilate. They were stripped of language, culture, and connections.

“What happened to them, that was even colder than what happened to us,” Dr. Williams says. “It was save the man, kill the ‘savage.’”

Congress enacted the Indian Child Welfare Act in 1978 to address concerns about the disproportionate removal of Native children from their families and communities.

“One of the first things a social worker will have to ask you is if there is any Native American heritage in your family,” says Tandrea Thysell, a former Bay Area social worker.

“If the child says yes, we have to investigate it and prove it – what tribe it is and if anybody is registered anywhere. They have every right to step into the child welfare process at any time and go, ‘We’ll take it from here.’ They’ll say, ‘We’re claiming this child in the name of the Yana tribe’ and the government has to step out of it.

“That’s for Indian children. Don’t ask me why they don’t do that for the Black ones.”

Building a culturally competent system that better serves children starts with acknowledging the harm that not having one creates, Dr. Williams says.

“We’re in one of those periods of time where history, if it doesn’t repeat itself, it definitely rhymes,” he says. “How we treat children now in foster care, how children have been separated from their families via the immigration conversation, we have to look at these things.

“The ontological idea of how these systems in America treat Black families is to separate them. It still is, but people don’t see it, of course, because it’s hidden under policy,” Dr. Williams continues. “Think about a lot of that welfare policy that we all know about; back in the ’70s, it was the asset tests and the man couldn’t be there.”

Mothers seeking public assistance are made to identify the fathers of their children and report any bank accounts and other monies they have access to. And while officially struck down by the Supreme Court in 1968, “man of the house” rules existed well beyond that. Caseworkers often made surprise visits to investigate whether a man was present. If there was, benefits were cut off. Activists argue the practice aided in the erosion of the Black family structure.

“This devastation of Black families in the name of protecting Black children, the color of America’s child welfare system, is the reason Americans have tolerated its destructiveness,” Roberts writes. “It is also the most powerful reason to finally abolish what we now call child protection and replace it with a system that really promotes child welfare.”

Leaders say current political shifts necessitate addressing racial inequities in the U.S. child welfare system. Dr. Williams suggests history provides a source of optimism, given Black people’s resilience in overcoming slavery and fighting for their rights despite immense challenges.

“Don’t get it twisted,” Dr. Williams says. “It was always a battle. We just have to be rooted in ourselves and have faith in ourselves and know what we’re up against.”