The silent epidemic: Tropical diseases in Texas

When you hear of diseases such as Chagas disease, leishmaniasis and toxocariasis, you might imagine an intrepid backpacker in the Amazon returning home to the United States with a worm-filled abscess or an unexplained fever. But for the estimated 12 million Americans living with neglected tropical diseases, travel to an exotic country isn’t part of the deal. Unless you consider south Texas to be exotic.

An epidemic of neglected tropical diseases, or NTDs, is bubbling just beneath the surface in the United States. NTDs include diseases such as dengue, chikungunya, West Nile virus and murine typhus. Some, like murine typhus, were banished from the U.S. in the first half of the twentieth century through diligent public health campaigns and interventions such as trapping rats. But they’re back.

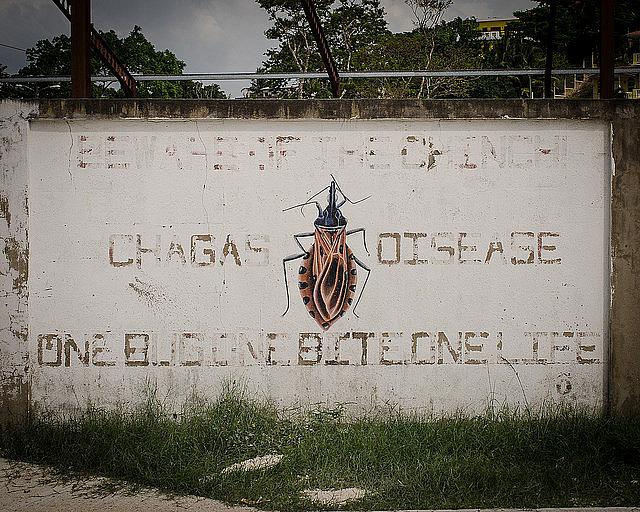

It’s an epidemic that experts describe as silent. That’s not because the diseases are mild: murine typhus, spread through a rat-biting flea, can cause swelling of the liver and spleen; leishmaniasis causes disfiguring skin boils and Chagas disease can lead to heart failure. The epidemic is silent because of who is infected: the poor.

Poverty is the single biggest risk factor for infection with an NTD, so it’s no surprise that the epidemic in the U.S. is focused in Texas, the uninsured capital of the country. Texas is home to the nation’s poorest metropolitan areas. Almost one in five Texans — that’s more than 4 million people — lives below the poverty line, according to the American Community Survey. It's worse for children: More than one in four children in Texas lives in poverty, a proportion that’s increased 47 percent since 2000. Most are Hispanic and African American.

Undiagnosed and untreated NTDs trap the impoverished in a cycle of sickness and poverty. Infection with the cysticercosis tapeworm is now a major cause of epilepsy among poor Texans. And toxocariasis — infection with the larvae of a roundworm — causes epilepsy and developmental delay in children.

Experts say hundreds of thousands of Texans are infected and that those numbers are likely underestimates. Without NTD surveillance systems, they say thousands of infections go undetected. When Houston blood drives started testing donors for Chagas disease in 2007, the parasite was found in the blood of Houstonians who had not left the country in years. “When we start looking for these diseases, we find them,” said Dr. Peter Hotez, dean of the National School of Tropical Medicine in Houston. “The problem is, we’re not looking.”

A lack of surveillance is not the only issue. Tropical medicine experts say that doctors trained in the U.S. are not able to diagnose and properly treat NTDs. A recent study of doctors in Texas by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found only 6 percent of those surveyed could correctly identify prevention measures for dengue. And less than half of the doctors knew when a patient with dengue needed an urgent blood transfusion.

Doctors aren’t the only ones who are unprepared. Texas’s public health system was deemed one of the countries least prepared for an outbreak of infectious diseases by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and Trust for America’s Health.

It’s this combination of factors — an unprepared public health system, a lack of disease detection, inadequately trained doctors and more people living in poverty — that is fueling the silent epidemic. My 2015 National Health Journalism Fellowship project will investigate how many heart failure, asthma and epilepsy patients in Texas are living with undiagnosed NTDs; how these infections trap communities in poverty; and what public health and medical systems should be doing to stop this epidemic.

To find the patients affected and the tropical medicine doctors caring for them, I’ll travel to disease hotspots throughout Texas. And for a Brit, those locations count as exotic.

[Photo by Daniel Neal via Flickr.]