In South Los Angeles, A Bold Plan To Address Health Disparities

Image courtesy of Rob Waters

Across the country, health providers and public health leaders are developing cutting-edge ways to address the underlying conditions that play a huge role in determining the health of a community and its residents. This is part three of Profiles in Innovation, a series of interviews with health leaders who are creating interventions that improve the health of whole populations, as well as individual patients. Read Part 1 here and Part 2 here.

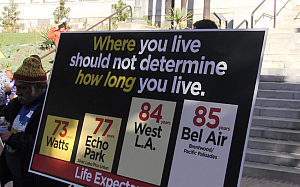

When Jim Mangia looks out at his adopted city of Los Angeles, he sees a place of enormous wealth and first-class hospitals alongside neighborhoods where low-income people suffer from preventable conditions and lack basic access to care. And he sees a place where people in some neighborhoods die, on average, 12 years earlier than those who live just a few miles away.

As president and chief executive officer of St. John’s Well Child and Family Center, a network of 10 community clinics in south Los Angeles, he has been working to provide care for the residents of south Los Angeles and to amplify their voices. Now he and his colleagues are adapting an idea that was first rolled out in Massachusetts—the creation of a wellness trust.

In the St. John’s proposal, this fund would be financed by revenue from the city’s hospitals and would pay for prevention and community health efforts. Other proposals to create local wellness trusts in California are also being developed. On Tuesday, the clinic kicked off its drive to create a Los Angeles wellness trust as it hosted the 4th annual South LA Health and Human Rights Convening.

Mangia has led the clinic for the past 20 years as it grew from three to 300 staff members. It now provides care to 50,000 patients, who together make 150,000 clinic visits a year. I spoke with Mangia about St. John’s dual role as a health provider and community organizer—and about the effort to create a wellness trust.

Jim, let’s begin with a thumbnail overview of the health of Los Angeles as a city and how it differs by community.

If you’re talking about LA, you’re talking about a tale of two cities, of vast differences in life expectancy and health status depending on what ZIP code you live in. If you live in Bel Air or Brentwood, you make more than 12 times the per capita income of residents who live in South LA or Boyle Heights. You live 12 years longer. There are just vast health disparities, particularly between the west side and south and east LA.

More than 30 percent of kids in some neighborhoods in south and east LA are obese compared to less than 12 percent on the west side. Less than 10 percent of adults in south LA are eating the recommended servings of fruits and vegetables every day. There’s less than half the park space there is on the west side. The diabetes mortality rate on the west side is 14 or 15 per 100,000 and in south LA it’s 43. That gives you a snapshot. If you live in Watts, your life expectancy is 72.8 years; if you live in Bel Air it’s 84.7.

Give me a brief description of St. John’s, what it does and why it’s unique.

St. John’s is a network of federally qualified health centers that provides medical, dental and mental health care—more than 150,000 patient visits a years. We feel very strongly that health is a fundamental human right. If you’re talking about health, you’re talking about more than health care. Our approach is comprehensive and holistic. We recognize that prevention and intervention around issues such as the availability of fresh fruit and vegetables in your neighborhood, the amount of park space, the availability of stable and living-wage employment – those are all factors and we engage those through prevention activities and programs, advocacy and policy work as well as the provision of traditional health care services.

A focus on community health and prevention seems almost built into the DNA of St. John’s. Where there any pivotal moments that led you all to look at the bigger picture and see the importance of community conditions?

Early on, there was a child who came to St John’s, 18 months old, and he couldn’t walk, couldn’t talk, couldn’t hold his head up. Mom thought he had some kind of developmental disability or was mentally retarded. She’d been everywhere to try to find out what was wrong. I’m from the east coast, where there’s a history of knowledge about the impact of lead poisoning. People here did not understand that any building built before 1978 for the most part contained lead paint and lead hazards. In the areas where we were working in south LA, almost all of the housing stock was built before 1978.

So we said, “Has the child been tested for lead?” And the Mom said, “What’s that?” We did a blood test and the child’s blood lead levels were through the roof. We referred that child for chelation therapy and were able to take care of it but we recognized that more than 80 percent of the housing in south LA is substandard, mostly built before 1978. If you don’t have peeling paint in the unit, you have paint dust, especially with slum housing conditions and repairs not being made.

Kids are crawling on the floor, pulling themselves up on the windowsills, putting their fingers in their mouths and getting lead poisoned. So we started to test every single child under the age of 6 who came into our clinic and found that 53 percent had elevated blood lead levels. We worked with other community partners in our neighborhood and developed this program called Healthy Homes, Healthy Kids. We went into these housing units and did interventions using low-tech and cleaning products as well as engaging with landlords to make repairs. We saw a 95 percent reduction in blood lead levels and 100 percent reduction in asthma hospitalizations.

I think that kid and the decision to test every child who walked through our doors from that point forward really taught us about the impact of the environment on family health—whether they live in healthy housing, whether there’s a park nearby, whether there’s a grocery store with fresh fruit and vegetables that are affordable.

St. John’s is now joining with partners to push for a wellness trust in LA. What’s the basic idea here?

The idea of the wellness trust is to create a pool of money that can effectively address the social determinants that are making our families sick and the vast disparities in health and access based on which ZIP code you live in. Health and wellness trusts are beginning to be looked at across the country. In California, we have a state law which mandates that a certain percentage of profit made by hospitals be spent on community benefits.

If you look at where the money is in healthcare, it’s with hospitals, health plans and insurance companies. So if you’re going to reorder the priorities of a healthcare system in a particular area, you have to use the resources of the system’s wealthiest elements. The issue is: Are these community benefit dollars actually being used for community benefits? I think some are and some aren’t. We’ve done research and know that cities and counties have some power to decide how those community benefits are spent. It’s through that process we think we can create this trust.

How might a wellness trust’s money be used?

It could be used to support prevention at the community level, to make grants to organizations to support exercise and fitness classes and nutrition education and urban gardens. It could be used to help create an insurance product for people that are not going to be covered by the Affordable Care Act— mostly the undocumented—so they can access health services. It could be used for infrastructure to build more community health centers or safe places to exercise.

How would hospitals contribute to this?

We would hope that hospitals would see this as an opportunity to contribute to the community and help eliminate health disparities and would voluntarily target their community benefits dollars to go to this trust. The trust could be set up by the city council or the county board of supervisors. The county has jurisdiction over health so if the board of supervisors is interested that would be the better choice in my opinion.

Who’s supporting this idea and where do you need to make gains?

It’s a labor-community coalition which I think is very significant. Labor and community organizations don’t always work together. A lot of community organizations in south LA are part of this. We’re in the initial stages, just beginning to build that coalition. There’s a lot of receptivity to it.

How soon could this come up for a vote at the council or board?

Could be in the first quarter of next year; could be later. We’re just testing the waters. The political leaders we’ve spoken with are intrigued. We’re just in the initial conversation; we haven’t asked anyone to sponsor it yet.

Have you had conversations with hospital administrators?

I think those conversations will happen early next year in a substantive way. We don’t know what the response of hospitals is going to be. They may say this is a great idea, we want to be part of an effort to eliminate health disparities and we’re willing to put community benefits dollars into this trust. We don’t know yet. I’m hopeful they will do the right thing.

St. John’s is very focused on empowering your patients and the south LA community to be active. How do you do that?

We’ve set up what we call Right-to-Health Committees as a way for our patients to express their advocacy and policy desires around health care and health access. They engage externally, organizing patients to take action around health and health care issues. Internally, they meet regularly with management to provide feedback and make suggestions on how to improve the patient experience. We’re also building community. Many of these patients are engaged in our prevention programs, a lot of them are in our diabetes classes or our efforts to grow fresh fruits and vegetable in the neighborhood. They become empowered by taking control of their own health and that catapults them into becoming health activists.

Tell me about the gardening. I came down here a couple of months ago and 150 people were on your block planting community gardens. What’s that got to do with health?

It has everything to do with health. Access to fresh fruits and vegetables, healthy food, is critical to your health. By digging a garden in front of your house and planting the vegetables you’re eventually going to pick and cook and eat, you become engaged and learn the importance of eating and cooking healthy. That cycle is profound and it has a huge impact on a patient and family. We are about to start a dig-in at Dominguez High school where we have a school-based health center. There’s a huge plot of land that Compton Unified School district is providing for us to plant an urban garden that our patients will help care for.

What innovation would you most like to see bloom in LA to promote health and wellness?

A partnership between our elected officials, community organizations, labor and hospitals to create a wellness trust that would eliminate health disparities. That would be profound. If you’re going to eliminate health disparities, you have to look at more than healthcare services.

This post originally ran on Forbes.com and has been run with permission.