We avoid thinking about long-term care. Can well-told stories change that?

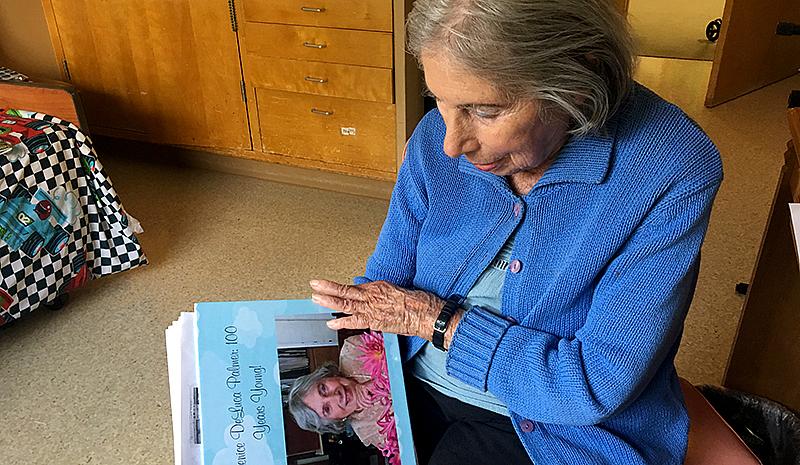

Berenice Palmer sits in her room at a San Francisco nursing home where she lives.

(Photo by Laura Wenus)

We’re all going to encounter aging in some way, and my sense in reporting a series on the issue and talking to other people about it was that for most of us, that encounter will come sooner and more abruptly than we expect. It might be when our parents begin to need some kind of extended care, or when we find we need it ourselves. Reporting on nursing home care and how difficult it can be to access affordable and quality long-term care for the elderly opened my eyes to how much we’d like to avoid thinking about the aging of our loved ones or ourselves, often out of some sense of self-preservation.

Unfortunately, it’s not in anyone’s interest to collectively underserve seniors. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services estimates that today’s seniors have roughly a 70% chance of needing long-term care service or support as they live out their lives. But as I learned, that’s often out of reach for those who need it. Nursing care is expensive — around $100,000 a year in the Bay Area, a figure that exceeds the median income of San Francisco. Lower levels of care than a nursing home, like home care or residential facilities, can also cost thousands of dollars a month — but subsidies can be more limited. As California Assemblymember Jim Wood says in the last piece in my series, “That's not a great reflection of how we take care of our vulnerable populations.”

Reporting this story really opened my eyes to how important it is to collectively think about how we ought to care for seniors, and how little we actually do that. I also came away with a few lessons learned about reporting long-form health stories.

My editor and mentor assigned me two self-assessment tasks that I’ll be keeping in mind in all of my future long-form work. First, signal to listeners or readers whether the situation of an individual they’re learning about in the story is common or uncommon. I think that was particularly crucial with Berenice Palmer, whose experience in a long-term nursing home bed I included because it was actually quite positive, but perhaps, as I pointed out throughout the rest of the series, quite a lucky break and not what listeners should necessarily expect to experience themselves.

The second recommendation was to find a source who might not necessarily appear in the final story but who has expertise in the subject and can assess whether a story is on the right track. Such a source can figure out whether the reporter has a good grasp on the basic premise of what’s happening. As a reporter — but not a health reporter — I found early research I’d done for the pitch useful later on (to quickly check, for example, that I was using the right terms and describing the relevant systems correctly). A person I could turn to for a second pair of eyes with expertise in the field but no skin in the game would have served as additional assurance. I’m very grateful to the first few experts who agreed to spend some time talking with me about their work and where they see as the biggest challenges in the industry, although they didn’t end up playing this specific role. For another project like this, I’d probably be more intentional about finding someone to work with in an advisory capacity — and put the tape recorder away.

Elder care and nursing care is a complex industry with many issues to balance. I knew that at some point I’d have to sit down and read over all my early research again and figure out a specific, narrow story idea for each aspect of what I wanted to get into. I didn’t. I flung myself into reporting, without being sure whether I was focusing on nursing homes only or other skilled nursing facilities as well, or whether I wanted to concentrate on long-term care or short-term rehab care. That was a messy way to approach this. There is also a plethora of important issues to consider in senior services and nursing care that I didn’t even touch on in this series. At certain points in the reporting I regretted not being able to go after those stories (the labor shortage in nursing, for example). But had I let myself try to pursue too many aspects at once, I wouldn’t have done these other stories justice anyway.

News stories become real when someone who’s been there tells them in their own voice and we can feel ourselves slip into their shoes. We all know it can be hard to find that person with the right timing. I don’t know how many times I pledged, in the latter third of this reporting process, never again to pitch a project unless I already had the individual whose story would make the issue resonate with listeners already on hand and ready to tape an interview. I knew it was going to be a challenge going in. Finding individuals to share their experiences was one of the first things I started working on, and it still took until the very final stages of my reporting to connect with the right people. My takeaway: However long you think it’s going to take, triple it.

I wish I had built more room into my stories, and in particular into my interviews, to allow my sources to lay out their own visions for how things could be improved, or their explanations for the root causes of the problems we face. Advocates, researchers, and industry leaders obviously spend tons of time thinking about the problems in their particular areas of focus (and I think they laid out really valuable points, especially on the topic of why it can be particularly difficult to find long-term nursing care rather than rehab). But patients and their loved ones are experts on their own experiences and have also spent probably more of their waking hours than they would like grappling with a problem that you are now reporting on for a broader audience.

Every time I report on health care, I’m floored by how simultaneously gracious and clear-eyed people who are wrapped up in reality-shattering life changes can be about what they’re enduring and why. If that resonates so much with me, I ought to make sure it’s shared with my listeners as well.

Check out Laura Wenus' fellowship stories here.