What does week's mixed Medicaid news mean for kids’ health insurance?

On Monday, we learned that Montana had officially become the 30th state to expand its Medicaid program.

But for proponents of Obamacare’s Medicaid expansion, the celebratory afterglow didn’t last long. Tuesday’s election returns from the Bluegrass State offered a quick reminder that universal expansion is not a fait accompli. As many have noted, Republican Matt Bevin’s “stunning victory” in the governor’s race portends major changes to that state’s embrace of Obamacare.

“Future looks shaky for Medicaid expansion and Kynect in Kentucky,” New York Times’ Margot Sanger-Katz tweeted Tuesday evening, while The Huffington Post’s headline writers took a more on-the-nose approach: “If This Kentucky Republican Becomes Governor, Hundreds Of Thousands Could Lose Their Health Insurance.”

It’s too early to say how Bevin’s governorship will ultimately curtail Kentucky’s Medicaid program. But in light of recent news that the rate of uninsured children has reached a historic low of 6 percent in 2014, it’s worth pointing out that whether a state expands Medicaid or not matters more than you might expect for children’s health insurance.

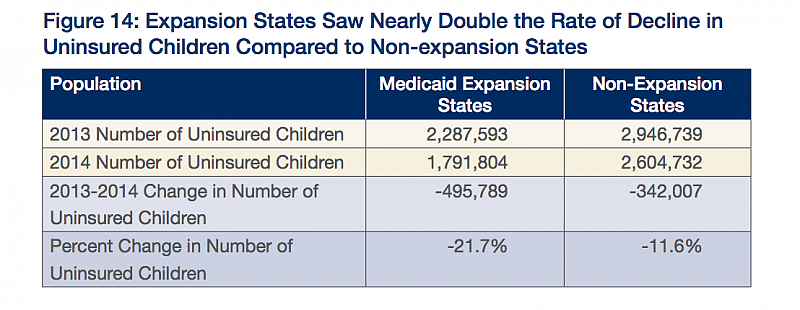

A report released last week by Georgetown University’s Center for Children and Families makes that clear. Drawing on the American Community Survey from 2014, the report provides a look at how the Affordable Care Act is changing children’s health insurance rates. States that expanded Medicaid to cover more uninsured adults saw their rates of uninsured children drop nearly 22 percent, compared with non-expansion states, where uninsured kids decreased nearly 12 percent:

The most obvious explanation for this disparity is what’s called the “welcome mat effect,” which I’ve written about before. The idea is that as parents enroll in public coverage, they’re far more likely to discover their child is eligible for coverage through a Children’s Health Insurance Program, for example. Longitudinal research from Oregon has shown that the odds of a child having health insurance are considerably higher when a parent has health insurance. When parents enroll in public coverage, mom or dad is far more likely to hear about and enroll their kid in a CHIP program.

That said, just because a state expanded Medicaid doesn’t mean it will automatically have a lower percentage of uninsured kids compared with expansion states. Louisiana didn’t expand Medicaid and had an uninsured rate for kids of 5.2 percent in 2014 (the state does lot of other things well to keep kids insured). In New Mexico, a state that expanded Medicaid, 7.3 percent of kids are uninsured. As Georgetown’s Adam Searing explains, the are a host of other important factors that matter beyond whether or not a state expanded Medicaid:

The reality of policy implementation, as always, is more complex. State decisions and action on outreach under the Affordable Care Act affected how many parents signed up for marketplace coverage, and when more parents came to the marketplace to find out about health coverage, more parents found out their children were already eligible for coverage too.

In Kentucky, it’s not yet clear how Bevin will remodel Medicaid. Many news accounts have noted his opposition to the Medicaid expansion “softened” over the course of his campaign. And Kentucky is already well ahead of the pack, with only 4.3 percent of children there uninsured in 2014.

Montana, on the other hand, is ranked 44th in the nation, with more than 8 percent of kids uninsured there. The state’s Medicaid expansion plan is a little different from blue-state plans, with most enrollees asked to pay 2 percent of their income in premiums. But if the broader trend holds, we might expect a big drop in Big Sky Country’s rate of uninsured kids in years to come, as more parents step onto the “welcome mat.”

[Photo by COD Newsroom via Flickr.]