Will the pandemic widen the achievement gap for California’s immigrant children?

Today, three in five kindergarteners in California speak a language other than English at home and half of school-age children in the state are the children of immigrants.

These children tend to fall behind as they enter kindergarten and are unlikely to catch up as they continue in school, a gap which has lifelong consequences for them and for our state as a whole.

The coronavirus pandemic has only compounded these gaps. The impact of the pandemic on young children in California, especially children of color, has been severe. Their families have experienced more serious health and economic outcomes. Their child care facilities and preschools have closed, kindergarten enrollment has plummeted, and when they are enrolled, children from vulnerable families are less likely to show up for online classes as parents struggle to meet families’ basic needs.

As one preschool principal told me recently: “We have a lot of families that have experienced evictions. We have a lot of families who have put their kids in some family day care or with grandma because they have to go to work. We have lots of kids that aren't showing up for their services because the family can’t. We have families who have five kids on Zoom at home and the bandwidth won’t handle the preschooler. If you’re going to choose between the middle schooler and the preschooler getting an education, a lot of people will choose the older child. ... People are making these awful choices because they have to.”

As an education reporter covering young children in California, I have kept a close eye on new attention to and investments in early care and education in the state, and on efforts to better support children from immigrant families at school.

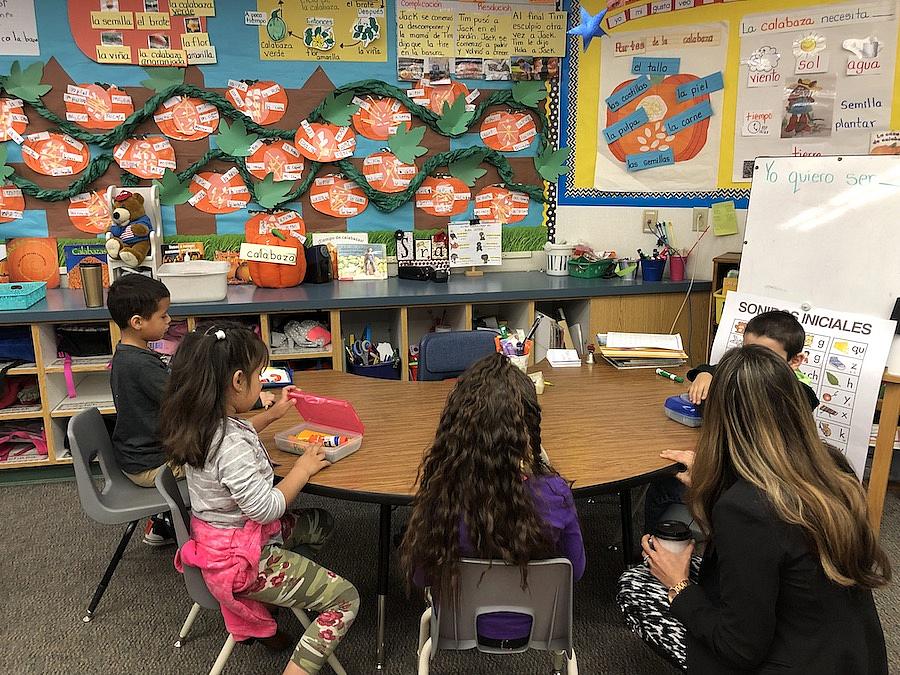

California has made some important recent policy changes to help these students, the biggest one being the passage of Proposition 58, which repealed the state's 20-year-old English-only education law. The state has also made important investments in recent years to train teachers to work with bilingual students and to help schools develop dual-language immersion instruction in pre-K classrooms, for example.

Yet to recover from this pandemic, advocates and educators say much greater investments will be needed.

For children who are learning two languages, the experiences they have in child care, preschool and kindergarten provide critical opportunities to build language skills, develop relationships with caring adults, and build social emotional and early academic skills that research shows is key to their success later on.

We don’t know what the long-term impacts of missing out on these early learning experiences will be. Teachers predict that children will have a tremendous amount of increased need when they return to school, both social and academic.

Through data analysis and reporting, and with support from mentors in the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2020 Data Fellowship, I’ll be examining in the coming months key data indicators on attendance, program closures, and kindergarten readiness to better understand how the pandemic has impacted young children’s learning, with a specific lens on young children from immigrant families in Los Angeles County.

I’ll be asking: How widespread is children’s learning loss? What are children’s specific academic and social/ emotional needs as they return to school or continue to learn at a distance? What has the impact been of a delayed start of kindergarten and of missing formal child care and preschool? Have these closures disproportionately impacted children from immigrant families and, if so, in what ways? What are teachers’ and families’ concerns? What extra supports are needed for early childhood educators? How can we help children heal from their trauma and the learning loss they have suffered during the pandemic?

Several years back, I spoke with Laurie Olsen, an advocate for bilingual children, who’s been working for change in schools for many years. “When we look to the future of the state,” she said “this is who we have. This is who there is to invest in.” Educators emphasize that children from immigrant families have assets the state needs, like bilingualism and biliteracy. Olsen calls it “an enormous gift to the state if we invest properly in their future.”

Today, we have a generation of young children suffering learning loss, language loss, and trauma from a pandemic, hunger and poverty. How well local and state governments respond in the coming year will have dramatic consequences for these children and all of our futures. Asking the right questions now, can help governments and schools make more informed choices. I hope this reporting can make an important contribution.