3 of every 4 jailed Louisville youth are black. Who can change that?

Kate Howard’s reporting on racial disparities was undertaken as a project for the Fund for Journalism on Child Well-Being, a program of the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism.

Louisville Metro Youth Detention Services is located on West Jefferson Street in downtown Louisville. Michelle Hanks

When Alicia Price’s son was cited by police for the first time, officers said he was part of a marauding group of juveniles “terrorizing” the Shawnee neighborhood.

A police report said the large group was causing unreasonable annoyance and alarm to residents. The officers labeled him for the first time as a gang member.

Price’s son was 13 years old. He was charged with disorderly conduct and tobacco possession.

That first encounter led to more: allegations of bike theft, a fight at school, and eventually carrying a gun. He spent last Thanksgiving, Christmas and his sister’s birthday locked up at Green River Youth Development Center, more than 100 miles from home. Price’s son declined to be interviewed and asked that his name be withheld, but he allowed a reporter to review his juvenile court record.

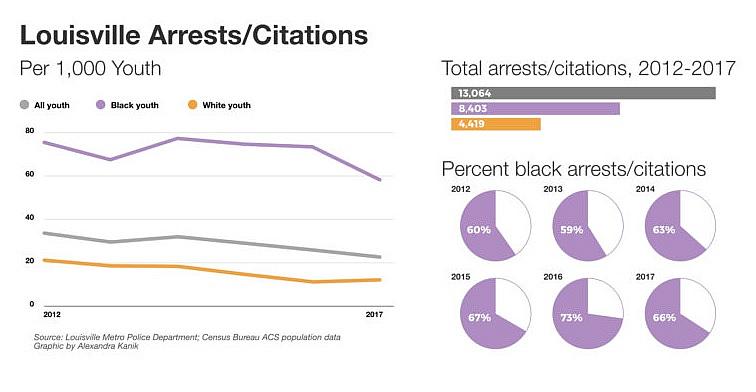

Advocates say this path is too common in Louisville, where the black population — and police enforcement — is concentrated in the neighborhoods of west Louisville. Though black youth are less than 27 percent of Louisville’s population, they represented more than 75 percent of the youth bookings in the city’s secure facility last year.

Even as the city’s leaders have turned their attention to the issue, those numbers indicate that the proportion of black youth has bounced between 75 and 80 percent since 2015.

“It’s not that black youth commit more crime, and therefore that’s why they’re in the system,” said Beth McMahon, chief juvenile defender at the Louisville Metro Public Defender. “They are treated differently from the beginning, a lot of times.”

Statewide reforms put fewer minor offenders behind bars than five years ago, and the Louisville Metro Police Department has cut its juvenile arrests by nearly half since 2012. But the smaller numbers of detained youth have only made the racial disparity more apparent.

The city has task forces and juvenile justice councils and a handful of nonprofits working with court-involved kids. But the trend persists, and worsens.

At every step, blame to go around

The conversation about disproportionality starts at the same place a court case does: the moment a youth is arrested.

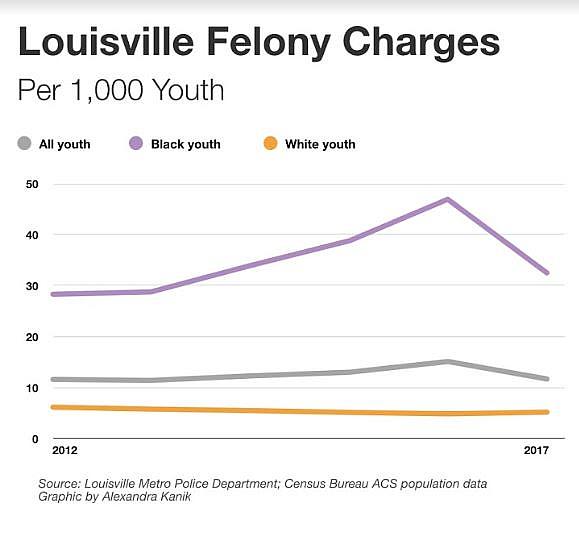

In 2012, black youth accounted for about 60 percent of the arrests in Louisville. By last year, it grew to 66 percent. About 72 percent of the youth arrested for felonies last year were black.

Major Jamey Schwab says LMPD knows that the way Louisville’s predominantly black neighborhoods are policed plays a role in what the federal government calls disproportionate minority contact, or DMC. But he said the LMPD must balance concerns about disproportionality with keeping those neighborhoods safe.

Schwab notes that LMPD is sitting down with the city’s public defenders, advocates and others to talk regularly about the disparity, and that alone is progress. Student resource officers, the police who initiate many arrests in Louisville’s public schools, are citing or arrest fewer youth, Schwab said.

But in Kentucky, a review by the Crime and Justice Institute found black youth had a higher representation in offenses that were not school-based last year, suggesting arrests occurred in their communities.

Schwab said the issue is not going to change “overnight.”

“You have areas within our community that have numerous challenges, and a lot of those challenges contribute to juveniles that are committing crimes,” said Schwab. “A problem in a neighborhood that’s taken a couple of generations is not necessarily going to be solved one day by LMPD saying, ‘We got a new policy.’”

Schwab also mentions something that comes up a lot in these types of conversations: that police officers represent just the first decision point among many down the line for young people.

“We kind of lose it from there,” he said.

The next place many Louisville youth go from LMPD’s custody is the juvenile detention center. Ursula Mullins, director of Louisville Metro Youth Detention Services, sees arrests as the best opportunity to address the disparity in her facility — “outside of what I think is the elephant in the room,” she said, “that there is systematic racism that we cannot pretend doesn’t exist.”

Since 2015, booking data provided by Louisville Metro Youth Detention Services suggests that black youth spend, on average, almost six days longer in lockup in Louisville than white youth.

Mullins would like to see more alternatives considered by the police before kids are even brought to her facility.

“Is there another avenue or referral and citation that we can do that will prevent kids from even coming in our back door (at the detention center)?” Mullins said. “All the numbers show that just from entering our back door, kids are already traumatized.”

Consider Price’s son.

On the day in March 2014 that he was charged with possessing tobacco, the police officer stated as fact that he was a member of a middle school gang called YNO. The report doesn’t explain why the officer believed that.

That month, the department was on high alert for that gang. In the weeks that followed, violence on the Big Four Bridge spurred a panic about “mob violence” the FBI attributed to YNO.

In the year that followed that first citation for tobacco, tensions remained high and black youth arrests peaked. Price’s son was arrested six more times.

For robbery and assault, after he was with a group of boys who knocked someone off a bike and stole it. For disorderly conduct, menacing and violating a court order, when he was hanging outside a convenience store and police said the group was threatening to shoot people. For criminal trespassing, when he was in an apartment complex where he did not live. Disorderly conduct and menacing, for a fight at school. Criminal trespassing, again. Then, his first felony: officers said he ditched a weapon over a fence as they approached.

He knows right from wrong, his mother says. He was on the honor roll and played basketball in middle school. He didn’t talk back to his mother; he still doesn’t. But Price said he started acting out when he was about 12, when she and his father broke up. After a close friend was murdered, she said, her child started carrying a gun.

For the earlier offenses, the teenager was deemed to be low-risk enough to go home. But with a gun charge, he became a felon using a firearm. At 14, he was locked up. He got angrier. More charges landed him committed to DJJ’s custody for nearly a year.

Price doesn’t condone her son’s behavior. She also doesn’t think he was ever a gang member. But it felt like every time he did wrong, the neighborhood beat cop was nearby.

“Why are you stopping these kids? Why are you emptying their pockets?” Price said. “I mean, you’re treating them like criminals, before they even have a chance do anything.”

Ideas for change are slow to take hold

In most cases after an arrest, youth make a stop at Louisville’s juvenile detention center on the corner of Eighth and West Jefferson streets, even if they aren’t going to ultimately be detained.

It’s at that secure facility where court designated workers — the state’s name for youth caseworkers in juvenile justice — are brought in to the process to help make a decision whether to keep or release a child.

“Most of the kids that come in are repeat offenders, and the police know these kids,” said LaKesha Jones, a court designated worker in Louisville. “Because they know the history of the kid, that kid goes to the detention center.”

In the rest of the state, a court designated worker gets involved before a child is taken to the detention center, said Christina Bronner, who oversees Louisville’s court designated workers for the state’s Family and Juvenile Services department. She said in an interview in January that Louisville’s system is the reverse.

It developed as a “convenience” for the officers, she said, but her office was pursuing a pilot program with LMPD where a court designated worker would be called before taking a youth to the lockup. That procedural change might result in less trauma and fewer kids ultimately detained, Bronner said.

But the pilot program has been put on hold, Bronner said this month, while LMPD is pursuing a different, unrelated pilot.

She also said one of the biggest problems with getting kids through a diversion with the court designated worker program is making sure they make their appointments and court dates. Her office has a plan to address that issue, too, by adding satellite offices in neighborhoods throughout Louisville.

A lot of kids don’t complete diversion just because they can’t get downtown and miss appointments, she said.

But the wheels are also moving slowly on that plan, too. Bronner said her department is waiting on agreements with the Neighborhood Place offices for space, and she hopes to move in before the new school year.

When the case continues on to court, Jefferson County Attorney’s Office juvenile division chief Chris Brown said his office is dealt a disproportionate hand. Year after year, he noted, more court petitions are filed against black youth than white youth.

“Basically from square one, when we process cases as an office, we’re already behind, so to speak, in terms of disproportionality,” Brown said.

Brown said his office doesn’t track many metrics by race.

Connie White, left, and her daughter, Lataevia Gaskin, listen during a Restorative Justice Louisville meeting in January 2018.

Data from the Kentucky Administrative Office of the Courts show that in Jefferson County, Brown’s office chose to bring a juvenile offender to court instead of allowing a diversion in almost 500 cases in 2017. That’s less than a third of the overrides they issued in 2012, but the disparity grew: more than 70 percent of the youth in those cases were black, Hispanic, multiracial or an unknown race last year.

Brown said weapon possession, any kind of physical injury to a victim or a prior criminal history are all factors his office considers in overriding a youth’s chance to go to diversion.

He hasn’t looked into whether some of that criteria might be exacerbating the disparity.

“It could be that some of the things that we traditionally look at as reasons to override diversion are inadvertently having an effect on the proportion of minority contact. And that’s a good question, and it’s one that I don’t know the answer to,” Brown said.

County attorney Mike O’Connell said the numbers are “what they are,” and more due to poverty and societal issues than the actions of his office.

“Is it because there is a fault of a human being doing something, or the failure of an office doing something? I would take issue with that, and say it’s the fault of our entire culture that has brought this on,” O’Connell said. “Unless there’s some ground zero cultural change going forward with federal and state participation, this is going to be a very bleak future for a lot of young people.”

Nonprofits bear burden of alternatives

A small nonprofit housed alongside Spalding University’s campus has been trying to move the needle on the disproportionality, one young person at a time.

Restorative Justice Louisville offers mediation for youth who are offered the program by a judge, and whose families agree to participate.

Lataevia Gaskin could be a 13-year-old with a fourth degree assault on her record. But instead, she sat in a government conference room on an evening in January, her mother next to her and Dationna Price across the table. They hadn’t really talked since the day in April 2017 when Lataevia jumped Dationna from behind.

“We know this is difficult for you guys to engage in this, and be sitting across the table from each other with a situation like this,” said Lou Jane Rupp, a volunteer facilitator. “We do believe this is a better way to do it though versus sitting in front of a judge and having this discussion. We want to focus on what happened, consequences, how people have been affected.”

They talk about what happened while Dationna’s mom, Ashley Patrick, reached under the table to hold her hand. Dationna wiped away tears while her mom recounted seeing a video of the assault on social media.

Ashley Patrick clasps the hand of her daughter, Dationna Price, during a Restorative Justice Louisville meeting in January 2018.

“All the sudden I just see her hair getting slung to the back, and then she’s on the ground and she’s screaming,” Patrick said.

Lataevia told her she was egged on by rumors that Dationna was going to start a fight, and she wanted to strike first. She said she knew she should have ignored it. She apologized. Dationna and her mom, though still working through the trauma, were satisfied.

Libby Mills, executive director of Restorative Justice Louisville, said this is the hoped-for outcome: victims who are heard and offenders who can feel empathy and own up to their mistakes.

But with its current funding, that program reaches about 150 youth a year. While the program aims to help reduce disparities, it still can only serve the kids referred by the courts. Since the program launched in 2011, about 65 percent of the referral base is black, Mills said.

“What is it that you need to do in order to move the dial?” Mills said. “That’s always been the question.”

Another program, Reimage, is supported by city funding and created specifically for youth who have spent time in the juvenile justice system. It includes case management, job training and GED services, but lacks enough volunteers to offer every youth a mentor, said Michael Gritton, executive director of KentuckianaWorks.

“We would love to be matching kids one by one, but that’s still a challenge,” Gritton said. “When we do it, it can really make a big difference for the kid.”

One solution many youth advocates mention is a civil citation program, like one in Florida, that routes lower-level offenders into a civil process and out of court.

The Louisville Metro Police Department is in favor of the program. In the nearly three years since the local juvenile justice working committee started the conversation, they have brought in experts from Florida and secured some grant funding for a pilot program that would be administered through Restorative Justice Louisville and Spalding University.

A pilot was targeted for last fall, and then this spring. But delays have come up.

Schwab of LMPD said there is still no target start date.

[This story was originally published by the Kentucky Center for Investigative Reporting.]

Alexandra Kanik contributed to this report. Contact Kate Howard at (502) 814.6546 or khoward@kycir.org.