Are children living near the border at greater risk of health problems due to sewage crisis?

The story was originally published by the San Diego Union-Tribune with support from our 2024 Data Fellowship.

Imperial Beach, California – December 23: Virginia Castellanos helps her daughter with her inhaler Jade Castellanos, 6, on Monday, Dec. 23, 2024 in Imperial Beach, California. Castellanos, a school nurse in Imperial Beach, is health conscious. She makes healthy meals for her family, works out each morning but her youngest daughter was diagnosed with asthma two years ago.

(Ana Ramirez / The San Diego Union-Tribune)

Virginia Castellanos, a South Bay Union School District nurse, is at work when her phone buzzes.

“It stinks really bad at Jade’s school,” reads the text message from her husband, who is walking their 6-year-old daughter to school in Imperial Beach.

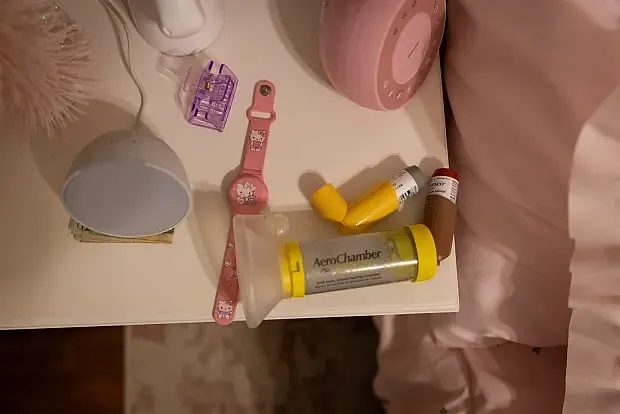

Inhalers by Jade Castellanos’ bed on Monday, Dec. 23, 2024 in Imperial Beach, California.

(Ana Ramirez / The San Diego Union-Tribune)

Castellanos can smell it, too, from her office about a mile away.

The odor comes from a toxic gas that they can’t see, but they can smell. It’s hydrogen sulfide and it’s a common byproduct from the millions of gallons of raw sewage routinely spilling over the U.S.-Mexico border by way of the Tijuana River.

Castellanos worries the gas is exacerbating Jade’s asthma, which often leaves her short of breath, wheezing and coughing. The young girl knows her way to the school’s health office to get her rescue inhaler when her symptoms intensify. She often misses school.

Castellanos has tried for years to pinpoint what is making her child sick. She’s pretty sure it’s coming from the river, but right now, she can’t prove it. Nor can tens of thousands of other residents in South County who have endured the noxious odors and accompanying symptoms for years and have had their concerns repeatedly dismissed or downplayed. They want to know: Is the air safe to breathe?

Months’ worth of data recently collected by the San Diego County Air Pollution Control District indicate that hydrogen sulfide is consistently detected in the air, but that’s not enough information to assess the long-term health risks of exposure to the gas and how it may be affecting students.

Schools in the area, which are some of the most disadvantaged in the county, say they lack the resources to gather sewage-linked data, leaving parents such as Castellanos to worry about the actual severity of the effects the cross-border pollution is having on their children.

Hydrogen sulfide is well known for its short-term risks in occupational settings. What is less known is what happens when people, especially those in sensitive groups, including children, are exposed to low levels over long periods of time.

Virginia Castellanos wakes her daughter Jade Castellanos, 6, up for school on Thursday, Feb. 20, 2025 in Imperial Beach, California.

(Ana Ramirez / The San Diego Union-Tribune)

Because of that “knowledge gap,” said Wilson Rumbeiha, an environmental health toxicology professor at the University of California, Davis, “we don’t know enough to dismiss that it is safe. Exposure is exposure.”

The San Diego Union-Tribune reviewed data from air quality monitoring stations in Imperial Beach, Nestor and San Ysidro – communities that have endured decades of cross-border pollution – and it showed persistent hydrogen sulfide levels that some studies and environmental health experts say can cause respiratory symptoms, such as coughing and wheezing. The review, which also included school attendance data, found that school districts in the border area do not track sewage-related absences, nurse visits, withdrawals or other impacts, gaps that may be obscuring the gravity of sewage-related consequences.

Measuring the risks

Reports of untreated wastewater flowing across the border stretch back to the 1930s. Despite significant treatment infrastructure improvements in the 1990s, facilities have not kept pace with Tijuana’s rapid population growth. Years of negligence and underinvestment in systems from both countries have only exacerbated the problem, leading to illnesses, beach closures and economic losses. More than 44 billion gallons of raw sewage mixed with polluted stormwater and trash made their way into the Tijuana River in 2023 — the most in the last quarter-century — and 36 billion gallons in 2024.

In recent years, reports have confirmed hundreds of waterborne, sewage-related illnesses among Navy SEALs, Border Patrol agents, and lifeguards. But far less examined: how cross-border contamination, specifically sewer gas, has impacted children, who are more sensitive to pollutants in the air. Measuring the health risks has tended to focus either on short-term or extreme exposure. Lost in the mix has been the effects of lower-level exposure over sustained periods.

People can experience symptoms such as nausea or headaches even during times when levels of the sewer gas meet state standards, said Cyrus Rangan, assistant deputy director for the Center for Healthy Communities at the state Department of Public Health, which worked with the San Diego County Department of Public Health to help interpret hydrogen sulfide threshold levels for public guidance.

“Those symptoms tend to be short-term and they tend to go away when the odors go away,” he said. But when people are frequently exposed to low levels, they may experience “constant symptoms where you’re maybe kind of feeling nausea, maybe all the time, or even having irritation in your throat or your eyes or something like that, on a fairly frequent basis.”

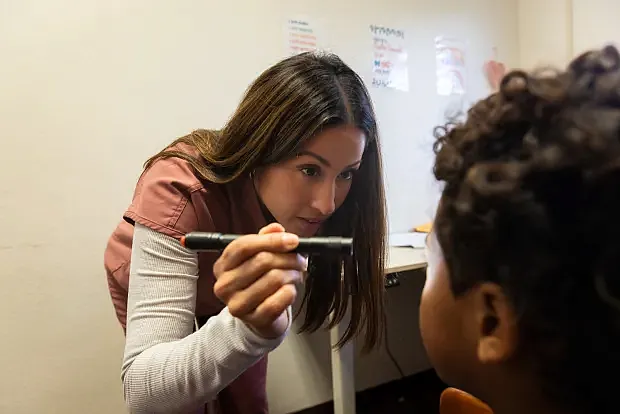

U.S. Virgina Castellanos, a school nurse for the South Bay Union School District, checks a student’s eye at Oneonta Elementary School on Wednesday, March 12, 2025 in Imperial Beach, California.

(Ana Ramirez / The San Diego Union-Tribune)

Like many parents living near the pollution, Castellanos believes there’s a link between the stench and her daughter’s health complications.

Jade’s doctor isn’t ruling out that possibility. During a visit in May, the doctor said tests eliminated environmental allergies as a source of Jade’s symptoms and said they “are more from irritants in the air,” her medical record shows. A prior visit in April confirmed Jade had pneumonia.

The girl’s doctor also wrote a note for the school stating that Jade’s “symptoms can get worse from air pollution exposure, including the Tijuana sewage smells.” On days “that are particularly worse,” the doctor advised that Jade stay indoors.

“It validates my concerns about it being linked to the Tijuana sewage,” said Castellanos. “I feel like a lot of people who don’t live in our area dismiss me when I tell them how it has affected my little one.”

Vi Thuy Nguyen, a pediatrician at Kaiser Permanente Otay Mesa with a background in environmental health, is part of a public health task force investigating the impacts of the sewage crisis. She said children are more likely to be exposed and are more sensitive to air pollutants because they spend more time outdoors and often play closer to the ground, where pollutant levels can be higher. She added that “a lot more kids” in her care who live in Nestor and Imperial Beach have recently shown the same symptoms as Jade, such as asthma attacks, and, surprisingly, pneumonia.

“Particularly, the pneumonias kind of stand out just because it’s not the right time of year,” Nguyen said. “We don’t usually see pneumonia in the middle of the spring.”

Nguyen said more residents who suspect they are experiencing sewage-linked symptoms should tell their doctors where they live and their “physical, mental and emotional symptoms.”

“The idea that your environment affects your health, most doctors did not learn in medical school,” she said. “And the idea that doctors like me have a responsibility outside the clinic, this also was not taught.”

Better documentation and data sharing, Nguyen said, could help show how the decadeslong crisis has impacted various aspects of life, including school attendance.

‘Missed learning time’

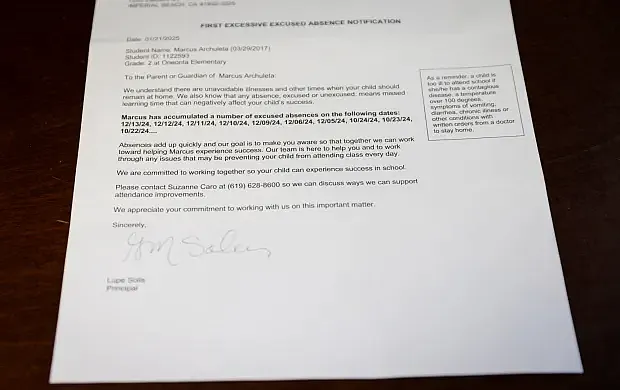

Renee Archuletta of Imperial Beach knew she would eventually receive a notice from the South Bay Union School District. It arrived in late January.

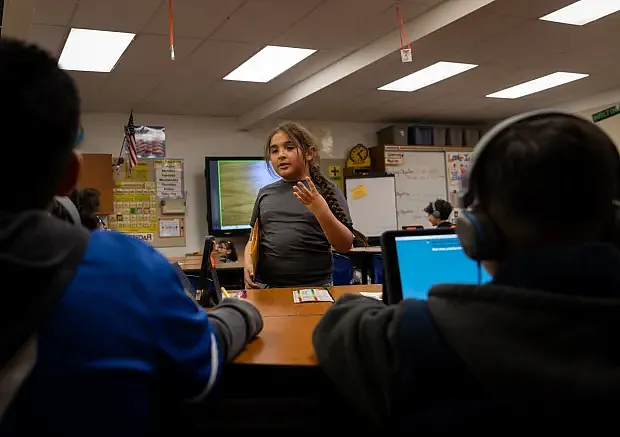

Second grader Marcus Archuletta talks to classmates on Wednesday, Feb. 12, 2025 in Imperial Beach, California. Archuletta has had several notes sent home discussing the amount of absences he has had.

(Ana Ramirez / The San Diego Union-Tribune)

“We understand there are unavoidable illnesses and other times when your child should remain at home,” the notice said. “We also know that any absence, excused or unexcused, means missed learning time that can negatively affect your child’s success.”

Marcus Archuletta has had several notes sent home discussing the amount of absences he has had on Wednesday, Feb. 12, 2025 in Imperial Beach, California.

(Ana Ramirez / The San Diego Union-Tribune)

Her then-7-year-old son, Marcus, had missed too many days in late October and December, the letter said. In recent years, as hydrogen sulfide odors have become more noticeable, Marcus’ symptoms and asthma attacks have worsened, his mother said.

The second-grader frequently experiences headaches, a runny nose and eye irritation. Closing windows, simmering pots of cinnamon and using an air purifier sometimes mask the odors that penetrate the house they rent, which is walking distance from Marcus’ school, Oneonta Elementary. His mother says she experiences similar symptoms, which disappear when they are away from town.

In October, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention conducted an in-person survey in and around the Tijuana River Valley.

The randomized survey of nearly 200 households found that 20% had their work or school performance affected. Most said they had trouble sleeping, experienced mood changes or difficulty concentrating. Additionally, 10.5% missed school or work due to the crisis, 3% changed schools or jobs, and 16% saw a school nurse, allergist or specialist.

Marcus, usually called Jr. by his family, left, looks for juice while his mother Renee Archuletta draws on her eyebrows on Friday, Dec. 20, 2024 in Imperial Beach, California. Renee believes her son has fallen ill from long-term exposure to aerosolized sewage pollution from the Tijuana River. He has stomach pain and headaches frequently as well as respiratory issues…..She has used all her time off at work because of illnesses she has suffered as well as her son needing to come home from school.

(Ana Ramirez / The San Diego Union-Tribune)

Tracking school absenteeism

Jade also is among those who have missed school because of health impacts her mother and doctors believe may be tied to or worsened by cross-border pollution.

Castellanos said that her daughter’s usual dry cough turned mucousy and thunderous on the night of April 25, a day that started with hydrogen sulfide levels reaching 209 parts per billion (ppb) – nearly six times the state’s hourly threshold of 30 ppb – and ended with concentrations between 60 and 107 ppb.

On April 28, Jade began wheezing at school, so she went to the nurse’s office to get her rescue inhaler. Later that afternoon, she was diagnosed with pneumonia.

Jade Castellanos, 6, talks to her father over FaceTime as her mother Virginia Castellanos gets ready to go to work on Thursday, Feb. 20, 2025 in Imperial Beach, California.

(Ana Ramirez / The San Diego Union-Tribune)

According to the federal Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, hydrogen sulfide can remain in the air for one to 42 days, depending on the season.

School absences sometimes rose after concentrations of hydrogen sulfide increased, according to data reviewed by The San Diego Union-Tribune. At Berry Elementary School in Nestor, a campus about a mile from the Tijuana River where an air monitor is stationed, the average hourly reading of hydrogen sulfide levels jumped above the state threshold of 30 ppb on Sunday, April 13, to 49.7 ppb. The elevated readings often coincide with spikes in sewage flows in the Tijuana River. In this case, over seven hours on the afternoon of April 12, the flows steadily rose from just under 1 million to 1.7 million gallons. Hourly hydrogen sulfide levels also climbed late that night into the early morning hours of April 13 from 1.9 to 15.7 ppb.

Sometimes when the hourly averages exceeded the thresholds, school absences rose. In this case, on Monday, April 14, the day after the high reading, Berry Elementary reported that 10% of its 300 students were absent. Berry has an average absentee rate of 7.6%.

Parents walk their children to Berry Elementary School on Thursday, Sept. 12, 2024 in San Diego, California.

(Ana Ramirez / The San Diego Union-Tribune)

But absences don’t always follow hydrogen sulfide spikes. At Berry Elementary, absences peaked on March 13, with a total of 75, or 25%. The average hourly readings of the sewer gas were around 1 ppb on March 13 and the day before, well below the state threshold of 30 ppb.

Castellanos, the school district nurse and Jade’s mom, said exposure affects people differently, and symptoms may not necessarily appear on a bad-odor day. She worries that the health ramifications are cumulative.

South Bay Union School District Superintendent Jose Espinoza said it’s “really frustrating” not to have the resources to gather and analyze data or hire someone who could specifically focus on the sewage crisis, which he said could help the district better understand how it is affecting the community it serves.

“This is not a district issue that we created or that we’re responsible for,” he said. “But we have to prioritize these things because of the safety of our students and staff.”

Efforts underway

Last month, school board officials approved spending about $400,000 to purchase air purifiers for classrooms, a move they said was necessary because it “ensures cleaner air for both students and staff.”

Schools have also hosted community meetings on the crisis, held classroom discussions about the pollution, had students write letters to the White House advocating for solutions and applied for additional air purifiers with the air district.

To tackle the root causes of the crisis, Lee Zeldin, the new administrator of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, has vowed to intensify pressure on Mexico to end the pollution. And on the U.S. side, he pledged to fast-track the expansion of a treatment plant at the border. In May, federal officials announced that a plan to expand the facility’s capacity to treat wastewater — from 25 million gallons daily to 35 million gallons daily — would take 100 days rather than two years.

But many in the region acknowledge that the problem has grown into a public health emergency. That’s why county leaders have committed to doing more. On June 24, the county Board of Supervisors approved exploring a plan proposed by Imperial Beach Mayor Paloma Aguirre that calls for appointing a “county sewage crisis chief,” upgrading air filtration systems at local schools and day cares, and launching in-depth public health and economic impact reports.

Jade Castellanos, 6, feeds her pet cat on Thursday, Feb. 20, 2025 in Imperial Beach, California.

(Ana Ramirez / The San Diego Union-Tribune)

Espinoza said schools in his district are encouraged to follow the guidelines the air district developed. When odors exceed the state’s hourly threshold, schools are encouraged to limit outdoor activities, have rescue medications on hand for students with asthma and use air purifiers in buildings without HVAC systems.

Castellanos would like to see districts go a step further and mandate that schools limit outdoor activities when the air quality is poor. But she’s not waiting for that to happen at Jade’s school. She’s transferring her daughter to a new school in Coronado in the fall, where the air quality is better.