Asian Youth Face Housing Instability After Leaving Foster Care

The story was co-published with AsAmNews as part of the 2024 Ethnic Media Collaborative, Healing California.

"Kim," a 21-year-old former foster child of Korean American heritage.

Photo courtesy of Kim

In November 2019, Kim was sitting in AP Human Geography class at her Bay Area high school when an administrator pulled her out of the room.

A police officer outside asked what had happened to the 16-year-old’s arm, ragged under her torn sleeve. Kim, who declined to share her real name out of privacy concerns, initially lied that she had fallen off her bike.

When she eventually disclosed that her father had kicked her in the back and sent her sliding on concrete, the authorities took her to an emergency shelter and called Kim’s mother.

Kim’s mother, believing that Kim had called the cops on the family, relinquished her parental rights by refusing to retrieve her daughter from the facility. Thus, at age 16, Kim joined the 1% of foster children in the U.S. who are of Asian descent.

Now 21, Kim is part of a group of “transitional” young adults 18 to 24 years old who are aging out of the foster care system, and face heightened risk of homelessness. But because she is Asian, Kim is part of a group that is rarely counted in research or included in conversations on culturally competent social services.

Her challenges in finding a stable home remain largely invisible to those around her.

An invisible and growing problem

According to the National Foster Youth Institute, half of all unhoused people in the U.S. went through foster care at some point in their youth, and one in five foster kids become unhoused upon turning 18. This is when most become “emancipated” from foster care, which means that they are no longer eligible for social services they accessed as children.

In California, the state with the highest level of foster placements and some of the highest housing prices nationwide, organizations serving Asian communities are turning the volume up on their demands to include Asian foster kids in conversations about social services access.

This is because Asian people are both the fastest-growing ethnic group in the country and have the largest percentage increase of any race or ethnicity entering homelessness.

Sacramento County’s point-in-time count of homelessness conducted in January revealed that one out of four of the unsheltered people who make up 40.4% of the total homeless population had been placed in foster care as minors. And 8% of the county’s homeless were between the ages of 18 and 24.

The most recent available point-in-count reports by Alameda County and San Francisco County have found similar statistics.

Community organizations, program facilitators, and former foster care youth are trying to weave together better safety nets to catch Asian foster kids before they end up homeless amid unaffordable housing prices and high living costs..

Woman, interrupted: one Asian woman’s journey transitioning out of foster care

When Kim entered foster care, she left her life everything she knew to move in with a single White foster mother in a rural area hours from the Bay. She transferred to a small, mostly White local high school.

Her relationship with her foster mother soon soured as the woman became verbally abusive and mentally unstable, throwing around racist microaggressions.

Because of the lack of Asian representation around her, Kim actively strained to hang onto her Korean identity while her caretaker urged her only to embrace American culture and excise Asian content and food.

Kim said that the worst part of being an Asian person in foster care was not being able to eat or cook the food of her heritage.

“With my foster mom, she was strongly against fish-smelling foods and other strong-smelling foods other than American. This lack of soul-satisfying food led me to binge-eating from stress and the lack of satisfaction from not being able to eat what I considered food that reminded me of home,” she wrote, in a text to AsAmNews.

By the summer of 2020, Kim was having ocular migraines from acute stress, her vision blurring. She tried cutting herself. Ultimately, she called her case manager in Alameda County.

He grudgingly arranged to move her up to Sacramento through one of California’s Transitional Housing Programs (THP) that help current and former foster youth establish safe living situations and self-sufficiency. THPs were made possible by AB12, an extended foster care provision passed by California in 2010, effective in 2012.

This odeng, or eomuk guk, was the comfort food that "Kim" was forbidden to have in her first foster home.

Photo by Chloe Lim

For her final supper before leaving her first foster home, Kim cooked up a steaming pot of odeng, a comfort dish containing colorful fish cakes and cuts of mu radish steeped in hot broth made of dried anchovies and kelp. Carrying two trash bags, a suitcase and a backpack of belongings, she moved to the Central Valley and entered a THP house.

Taking up space that someone else deserved more

“Because of my appearance, I was told directly by my other foster kid roommates that they thought that I had more privilege than them,” Kim recalled.

The other children had decided that Kim must be from a wealthy family when she asked if there was a recycling bin available in the house.

As high school graduation approached, Kim grew increasingly depressed and anxious about her future. She barely graduated, and only by the grace of a counselor who made special exceptions for her.

Social media shaped and warped her reality. When she joined TikTok, she saw strippers glamorizing their lives. She saved the information for her future – she couldn’t count on housing support forever.

She also realized that she could be a “hot commodity” as a young Asian woman and sought a controlled environment in the interest of her safety, remaining sober and adamant about refusing sex work.

In 2021, after finishing high school and turning 18, she applied for a job as a waitress at a strip club and moved into a friend’s family’s house for $400 a month. Within two weeks, the parents learned where she was working and cast her out. Kim sought refuge in rent-free THP housing again.

The break on rent enabled her to stop working at the strip club while bouncing around in THP housing. She became adept at clearing out of a dwelling quickly despite a hoarding problem originating from the lack of consistency and security in her life.

From 2022 to 2023, The California Child Welfare Indicators Project (CCWIP) at the University of California calculated that the rate of youth exiting foster care by early emancipation or “aging out” doubled from 7% to 14%.

Kim was part of this wave and could have continued living in THP housing until she turned 21. But In November 2023, when she was still 20, she found a room to rent in a house on Facebook Marketplace with two other women who each paid $1120 a month.

A part of why she left early was that she felt like she was taking up a space that someone else deserved more.

“I believed other people when they said I was more privileged, even though I was literally in the same spot as them,” she said. She also wanted to try to survive on her own before aging out of extended benefits.

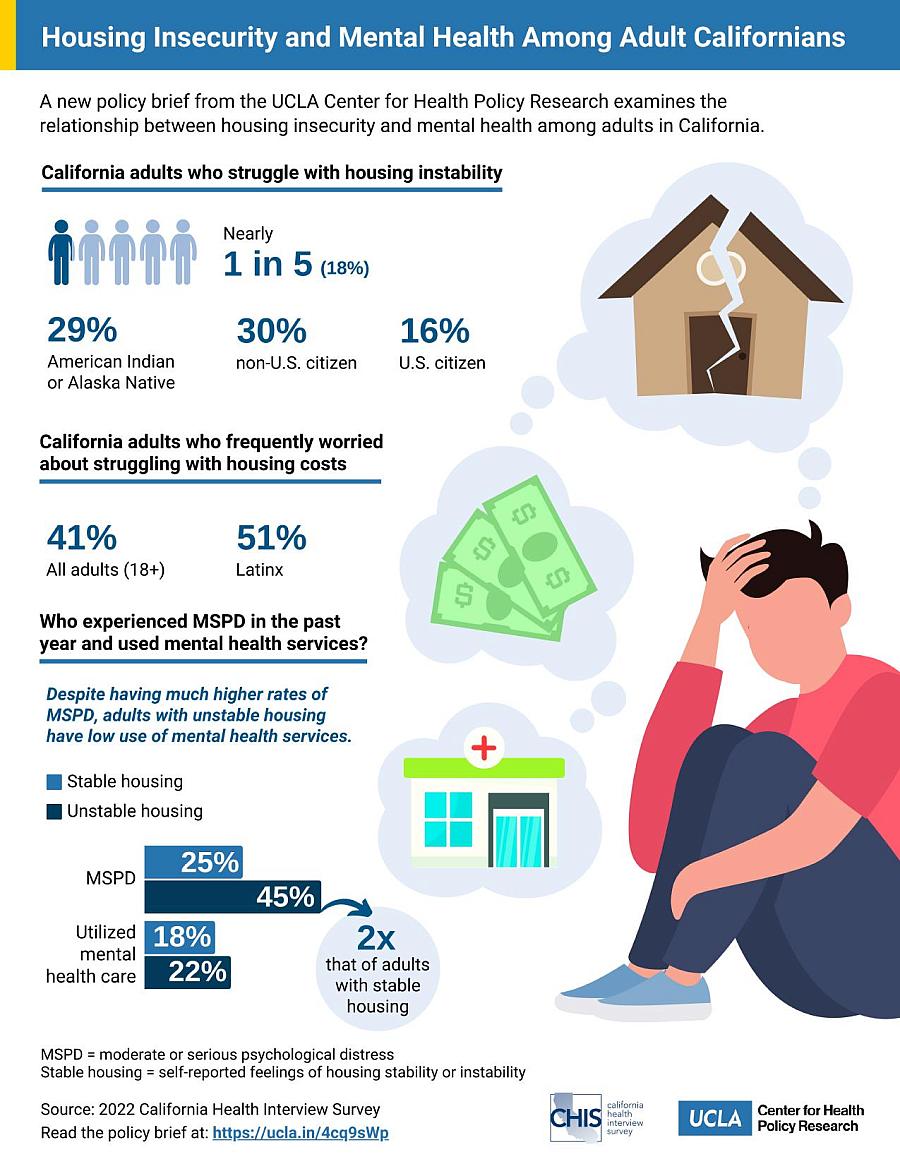

A recent report by the UCLA Center for Health Policy Research used 2022 California Health Interview Survey (CHIS) data to show the mental health effects of housing instability on adults.

UCLA Center for Health Policy Research. CHIS and UCLA.

The endeavor started off well. She exited a toxic relationship. She began eating healthy and working out. She continued therapy, set up by her social worker when she first entered foster care.

After a slew of bad experiences with social workers, she connected with a case manager of Alameda County’s Independent Living Program (ILP) for life skills education and support. The program was created by the Foster Care Independence Act of 1999.

He set up gas and rent reimbursements through ILP and sent her resources and information about general support.

“He sensed and heard my urgency and responded in the same way,” Kim said. “Having someone believe and support me was huge.”

Organizations that help foster youth find housing face cuts

The case manager Kim met was in his last months working for an Oakland organization called Beyond Emancipation, known as B:E for short.

B:E has been administering the ILP for Alameda County for eight years, helping young adults aged 18 to 24 transition out of foster care and into adulthood.

In addition to offering career counseling and assistance with school tuition and living expenses, B:E provides transitional housing in shared homes and vouchers for government-owned buildings.

As of now, foster kids can only access extended care if they are in the system one day past their 18th birthday.

James Keovilayphone is B:E’s coaching manager who oversees a team of staff who coach young adults toward self-sufficiency. He told AsAmNews in a video call that most foster children approaching 18 reunite with their original families or make living arrangements with extended family members or friends.

If they lose that new home, most commonly by being kicked out, they are likely to become unhoused, with no more access to extended foster care benefits because their cases have already been closed.

A 2024 report by the Pew Research Center reported that 57% of all Americans aged 18-24 are living with their parents.

Simone Tureck Lee, housing and economic mobility director at John Burton Advocates for Youth (JBAY), a non-profit advocating for youth in foster care or homeless, said that there’s a reason why this is happening.

“Many young adults aren’t living with their parents because of a lack of desire to live independently—they can’t afford to move out,” she said. She added that foster kids often do not have the option to live with parents or relatives, putting them in a difficult position of suddenly seeking homes on the private market without the tools to do so.

“They don’t have rental history, they don’t have credit, they don’t have someone to co-sign. They’ve never had to go out and find housing on their own. They’re discriminated against because people don’t think they’re going to be an ideal tenant,” she said.

Compounding these challenges is the fact that housing prices tend to exceed extended benefits to transitional youth.

James Keovilayphone, left, and Teshika Hatch, right, are the coaching manager and new transitions director of Beyond Emancipation (B:E), which will continue administering the Independent Living Program (ILP) for Alameda County through Oct. 1.

Photo by Jia H. Jung

The legislative path forward

JBAY and other advocates lobbied for more money to help youths aged 18, 19, and 20 placed in Supervised Independent Living Placement (SILP), a foster care placement for nonminors who live independently and are responsible for finding their own housing.

SILPs are the least-restrictive placement option for independent young adults, allowing them to receive their monthly foster care payment directly, rather than through a foster caregiver or placement provider.

In 2023, the state legislature established the SILP Housing Supplement to increase the monthly foster care payment youth in SILPs receive, which is currently $1,258. The SILP Housing Supplement would have increased this payment amount based on Fair Market Rent in each county.

The raise was to take effect in July 2025. But California, experiencing a budget deficit and in the middle of launching major child welfare reforms, eliminated the program for the 2024-2025 budget year. Instead, the state allocated the funding to a different plan that will increase the direct payment to youth in SILPs to $2,288 across the state.

The increase is part of a greater plan that targets the earlier stages of the foster-care-to-homelessness pipeline and builds upon the Family First approach of working with families to prevent and reduce placement into foster care.

The only problem is that the raise will not be effective until July 1, 2027, if the California Statewide Automated Welfare System (CalSAWS) can process the new payment paths by that time.

“We’re very encouraged by this monthly payment increase for youth, but disappointed that young people will have to wait three years for this overdue change,” said Lee.

Lee said that foster youth will have to be savvy for the next two years because housing prices will continue to rise.

She said that there were lots of factors in youth homelessness and that declining support for transitional youth in favor of other initiatives is one of them.

“My prediction is that if we continue to see this decline in foster care, we may see an uptick in youth homelessness. We have to ensure that young people have access to foster care if they are being neglected or abused. Unfortunately, for older teenagers, foster care is not always accessible, and state and federal policy is continuing to trend in this direction,” she cautioned.

Meanwhile, JBAY, advocates, and legislators like Assemblymember Phil Ting (D-Calif., District 19) preserved $13.7 million for the 2024-2025 California budget to save the Housing Navigation and Maintenance Program that employs staff and programs to help current and former foster youth find and keep housing. The program also often assists former foster youth obtain federal housing vouchers.

Lee said that the upcoming presidential election and gubernatorial elections of 2026 after Gov. Newsom terms out will also affect how these budget commitments play out.

California Governor Gavin Newson, pictured in April 2024.

Bureau of Reclamation

Spokesperson for Governor Newsom: Discussions on foster care funding are "ongoing."

The intent of the child welfare reform that will roll out starting in 2027 is that, with basic needs met by caregivers who receive greatly increased stipends, more foster youth will become freer to access additional programming like the ILP transitional life skills education that B:E has been providing.

But on October 1st, B:E’s contract with the county terminates and will be given to Side By Side, an organization serving family members of vulnerable youth in addition to the youth themselves.

This means that B:E will no longer administer Alameda’s ILP, which means an end to providing housing and other life education skills offerings available under the program.

B:E remains the main hub and holder of other housing navigation and maintenance, education, and career coaching programs of the county.

“After the contract is over, B:E will still provide housing navigation support to coach youth around how to secure housing in the foster system. We will also provide education and career support,” Keovilayphone confirmed, in a text message.

Still, Keovilayphone said, “It’s going to be a major impact – we’ve got a little bit of time but it’s just around the corner.”

The staff is figuring out how the change could affect their roles, their operating space, their programming, and the fate of the students currently living in transitional community housing that will soon cease to be a part of B:E’s jurisdiction.

“If we had more support from the state, I’m pretty sure that we would continue offering transitional housing,” Keovilayphone said.

While not commenting on B:E directly, a spokesperson for Gov. Newsom wrote in an text message to AsAmNews that discussions on foster care funding were “ongoing.”

Demand for housing by foster kids who have just aged out continues to outpace policy. Keovilayphone said that 50 to 80 people are on the waitlist for the voucher program and that youth have waited over a year before to get into shared THP housing.

Teshika Hatch, who became director of transitions for B:E in February after working in education and college access, has been fielding approximately 10 housing applications a week for 10 THP living spaces that are mostly filled and soon to become unavailable, or at least go through a major overhaul.

She also said that, recently, one Lao American and one Filipino American had been among the applicants. Keovilayphone has noticed a visible uptick in Pacific Islander and Lao applications in just the past two or three months and is not yet sure if there is a particular reason why.

From one housing situation to the next

Kim’s ongoing saga is just one example of the massive , immediate effect that transitional funding or its reduction has on the thousands of young adults in the state who exit the foster care system annually.

After finding stable housing, "Kim" has filed taxes for the first time and enrolled in school again.

Photo courtesy of Kim

In May of this year, when she turned 21, Kim formally lost eligibility for ILP and other transitional assistance. She removed herself from a bad roommate situation and lived for $1,300 a month in a house with three men she didn’t know before paying $800 to live with three women, also strangers, the next month.

In order to keep making rent without stripping near her biological family and childhood circles, she juggled three to five low-skilled jobs – a blend of retail, brand promotion, and fast-food service.

But she rapidly amassed thousands of dollars of credit card debt with compounding interest from the frequent upheavals, even if she had intermittently lived rent-free and saved thousands from her short stint in nude dancing.

Kim knew that the fastest way to crawl out of her financial hole was to establish a safe and consistent living environment. Because of her traumatizing history living with multiple caretakers and cohabitants, this meant living alone. Most importantly, she wanted to be able to take care of a beloved pet dog, her most trusted companion, that was being neglected by her biological family.

There was only one way to afford this. Kim found another job at a strip club. The establishment’s offer letter immediately landed her a lease on a studio for $1,800 a month.

During her first week at work, Kim learned how much the economy had declined overall in her time away. She once averaged $2,000 a shift for dances and tips; now, she made hundreds to $1,000.

“Things are tough, but without the THP program I would have surely become homeless,” Kim said.

She said that what she has to do right now to afford rent was better than being treated like dirt at fast food franchises and scrapping around for spotty brand promotion gigs paying $25 an hour. Those earnings were never going to pay off her debts, help afford veterinarians’ bills, or save toward a home and the rest of her future.

To Kim, this is all a part of finally acquiring adult life skills that she feels she can learn now that the matter of housing is settled.

“I feel like a lot of people might think that I’m on a path to giving up, trying to go backwards. But I feel like I’m really moving forward,” she said, adding that she filed taxes for the first time this year.

She is already enrolled full-time in an associate degree program in the business administration program and is excited to get on a career track, likely in realty.

One day, she wants to buy up properties in the part of the Bay Area where she grew up and rent out units at attainable prices to people in her own situation.

This project is supported by the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism, and is part of “Healing California,” a yearlong reporting Ethnic Media Collaborative venture with print, online and broadcast outlets across California.