California is a reproductive rights haven. So why are women being forced into surgeries?

This project was originally published in The Sacramento Bee with support from our 2023 California Health Equity Fellowship.

While sitting with his mom Kaitlyn Weiss and brother Liam Weiss, 11, at home in Modesto on Aug. 2, Beau Weiss, 6, left, glances down at an image of midwife Jessica Johnson holding him as a newborn with doula Lori Fenner. Beau was a VBAC birth and his brother Liam was a C-section delivery.

Renée C. Byer

Kaitlyn Weiss felt a searing pain on the surgical table, surrounded by strangers. She was in labor and she did not want to be in that icy operating room, so close to the scalpel meant to cut her open.

When she felt that pain, she knew immediately, “This was my last opportunity to have some control over how this delivery was gonna go.”

The charge nurse yelled “stop pushing,” but Weiss bore down. Her water broke all over the floor. As the anesthesiologist balked at the puddle, his hesitation gave her enough time for her final, fervent pushes.

She rolled onto her side on the operating table and gave birth to her second child obstinately. Weiss said the round-bellied boy popped out of her vagina “like a butterball,” into the arms of the startled obstetrician.

This wasn’t how Weiss had pictured it.

The birth didn’t go the way the OB-GYN on call at Doctors Medical Center Modesto expected, either, though his plan was much different from Weiss’. She said she left the birth center where she’d been in labor for hours and showed up at the hospital March 12, 2017, seeking pain medication to ease her intense contractions while she continued attempting a vaginal birth. But when she arrived, the doctor said a vaginal birth was not an option.

During labor, the cervix dilates to 10 centimeters. Weiss’ cervix was at 9 centimeters when the doctor had his staff shave off her pubic hair and wheel her into the operating room. Weiss and her midwife said the doctor — the same man who oversaw her first birth — reasoned that, because she had had a C-section in 2012, he should give her another C-section.

The young mother, then 23, said the doctor later “boasted about the fact that he VBAC’d a 10-pound-3-ounce baby on the OR table. And I’m like, ‘You did nothing.’”

Krista Deans, a representative for the hospital, cited privacy laws and declined to comment on Weiss’ specific case, but said the story was “not an accurate representation of the care we provide.”

Weiss’ midwife, Jessica Johnson, was at the hospital that night and confirmed her client’s account. She said the experience wasn’t good health care. To her, it just illustrated the underpinnings of blanket bans of vaginal birth after cesarean across California: “Absolute ludicrousness.” Johnson watched helplessly as her patient came to the brink of being forced into a plainly unnecessary surgery she said repeatedly she did not want.

A cesarean can be a life-saving procedure. But it is a significant surgery — one that can put the person giving birth in grave danger. While a vaginal birth after cesarean, or VBAC, slightly raises the probability of uterine rupture, a serious birth complication, each C-section further increases the probability of bad birth outcomes, including future infertility and maternal death. A 2006 study in the journal Obstetrics & Gynecology concluded that “serious maternal morbidity increases progressively with increasing number of cesarean deliveries.”

At a minimum, a C-section is a painful and temporarily debilitating procedure that requires six weeks of recovery and complicates activities as varied as caring for a newborn, moving from a sitting to a standing position, using the toilet and sneezing.

Women could weigh these factors in consultation with their health care providers and decide for themselves what they want. But doctors, midwives, doulas and mothers told The Sacramento Bee that instead, many obstetricians and hospitals in California simply force women under the knife.

Some of that stems from genuine concern for an individual’s well-being. A bad labor outcome becomes more likely if the prior surgery was less than two years ago and the wound hasn’t had enough time to heal; if the C-section was in response to a situation likely to arise again; if the original incision was atypical; if the person has undergone multiple uterine surgeries.

But all-out bans aren’t about individuals — and these policies curtail women’s choices across California.

Kaitlyn Weiss tickles her son Beau Weiss, 6, in their home in Modesto on Aug. 2. She said on the day he was born, she had gone to the hospital for medication for the contractions. “The next thing they were telling me, I had to have a repeat C-section, and so in that moment it’s hard to advocate for yourself,” said Weiss.

Renée C. Byer

Years before Weiss pushed her baby out against her doctor’s wishes, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists — the OB-GYN professional association — came out against blanket bans on VBACs.

“Individual circumstances must be considered in all cases,” said Practice Bulletin 115, released in August 2010. “Respect for patient autonomy also argues that even if a center does not offer (trial of labor after a C-section), such a policy cannot be used to force women to have cesarean delivery or to deny care to women in labor who decline to have a repeat cesarean delivery.”

ACOG explicitly tells providers in a separate recommendation that “pregnancy is not an exception to the principle that a decisionally capable patient has the right to refuse treatment.”

Yet these coerced and sometimes forced surgeries happen routinely in California, a state whose leaders have prided themselves on enshrining women’s reproductive rights.

Out of 205 hospitals with labor and delivery departments, The Bee confirmed in July and August that 56 — 27% of the total — do not allow vaginal birth after a C-section. Staff in several hospitals noted that while VBAC may be allowed, it is discouraged, describing it as refusal of cesarean.

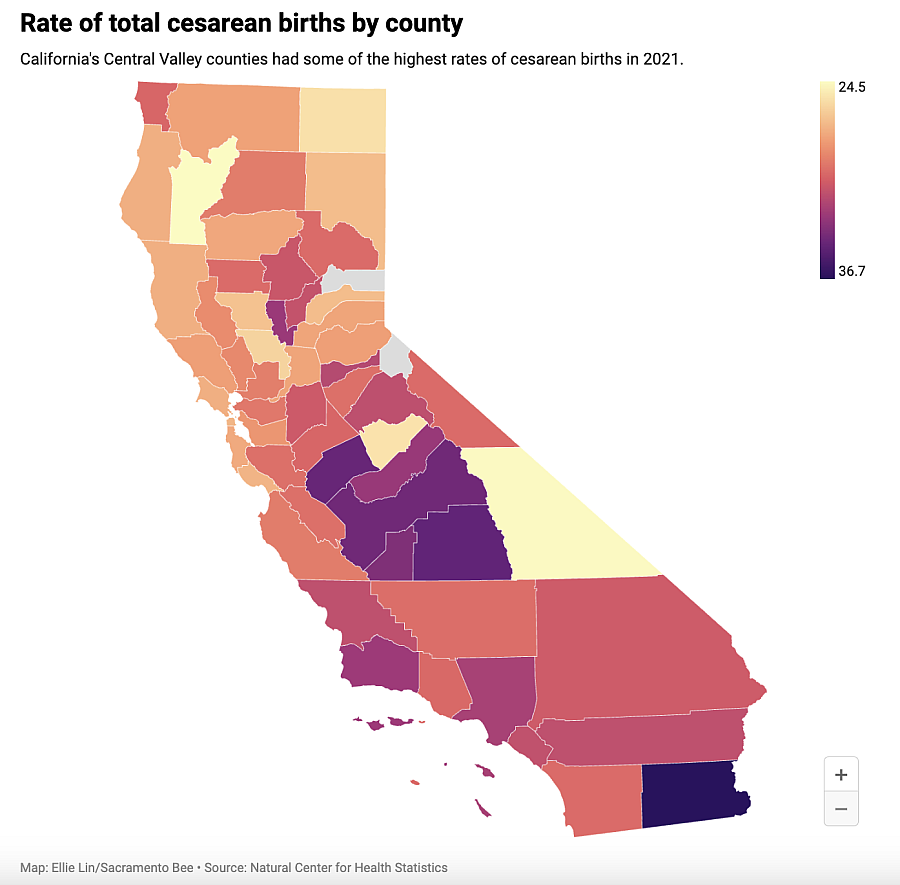

Even when hospitals allow people to attempt vaginal deliveries after a cesarean, certain doctors will not work with VBAC patients. That is a brutal reality for the hundreds of thousands of women who have had a C-section in the state and go on to have more children. Some of those primary cesareans were likely not even necessary: In California, 23% of low-risk, first-time births ended in surgery between 2017 and 2021.

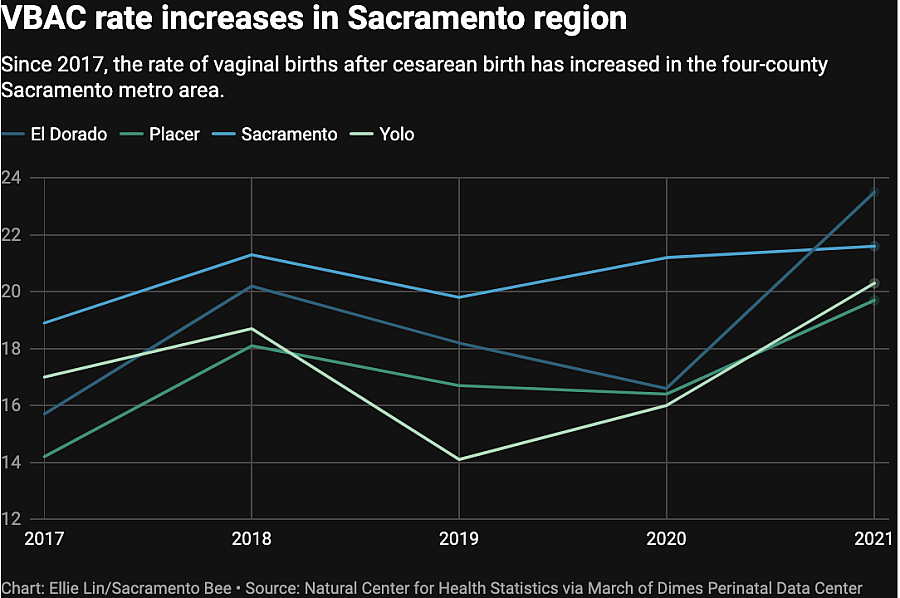

And data show that in the same five-year span, the average VBAC rate across all California counties — the rate of people who, having had a C-section, are able to have a subsequent vaginal birth — was just under 12%. That left a vast majority undergoing multiple cesareans: Nearly nine times out of 10, people having a baby after a C-section were going right back into surgery.

Madeleine Wisner, a licensed midwife based in South Sacramento, has a straightforward explanation for the lack of VBAC access: “It’s because we don’t give a f— about women.”

The coerced surgeries have made her conspiratorial. She now believes the authorities will restrict VBAC “more and more and more until people lose reproductive capacity and/or everyone just starts dying in childbirth.”

There’s no evidence of conspiracy. But there is evidence of infertility and death.'

Kaitlyn Weiss inspects her 6-year old son Beau Weiss’s face after wiping it clean at their home in Modesto earlier this month. Beau was a vaginal birth after cesarean, or VBAC. While a VBAC birth slightly increases the risk of uterine rupture, a serious birth complication, each C-section further increases the risk of bad birth outcomes, including future infertility and maternal death.

Renée C. Byer

A C-SECTION SNOWBALL EFFECT

“We know that repeat C-sections — and especially repeats numbers three, four — have much increased risks of hemorrhage, of infection, of abnormal placentas and maternal death,” said Amanda P. Williams, an OB-GYN and a clinical advisor to the California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative.

When she served on the California Pregnancy-Associated Mortality Review committee, she looked into some of these deaths.

“It came up all the time,” she said. “It’s directly impacting maternal deaths in those more complicated repeat C-sections, and then it’s indirectly leading to maternal death because of the placental abnormalities that get caused that then lead to a huge hemorrhages during the delivery.”

“It is,” she said, “one of the top reasons why people are dying from hemorrhage at the time of their birth.”

And while policymakers have understandably focused on reducing the primary C-section rate, the VBAC rate remains extraordinarily low, especially in lower-income and rural counties.

Stanislaus County, where Weiss gave birth, is in many respects a typical California county when it comes to VBACs.

Between 2017 and 2021, National Center for Health Statistics data analyzed by the March of Dimes Perinatal Data Center show that nearly 21% of first-time, low-risk births in Stanislaus County were by C-section. That number puts it well above the rate recommended by the World Health Organization of 10 to 15%.

Over the same span, the VBAC rate in the county fluctuated from outstandingly low to low. In those five years, it hit a nadir of 4.2% and, in 2019, an apex rate of 10%. Over the five years, the VBAC rate in the county was 7.3% — worse than the statewide average of 11.6% and the median of 11.1%, but not low enough to land it among the six counties with an average rate under 5%.

The numbers don’t account for women who may have attempted a VBAC and then, for medical or other reasons, ended up in surgery. Still, wealthier, more urban counties tended to have much higher VBAC rates. In Sacramento County, 20.6% of women who had a previous C-section gave birth vaginally. The highest VBAC rate was in San Francisco County, where 24% — nearly a quarter — of births after cesarean were vaginal births.

But that still left three-quarters of those San Franciscans having multiple C-sections.

And across the state, a disproportionate number of women undergoing repeat cesareans are Black. A 2018 survey by the California Health Care Foundation found that 42% of Black births in the state were surgical, compared to 29% of white births.

More of those are repeat cesareans because Black women are more likely to have a possibly unnecessary C-section for a first-time birth of a non-twin, head-down baby at 37 weeks or beyond, which in most cases is a low-risk birth. The California Department of Public Health said that in 2018, 28% of Black women in California giving birth under those conditions had a C-section; 23% of white women giving birth under the same conditions had a C-section.

Destinee Campbell, now 31, is certain her race played a role in her surgical birth in 2016, which she and her midwife, Wisner, blame on a “cascade of interventions.”

Destinee Campbell shows a photo on her phone to her daughter, Nayelieden, 6, on Aug. 11 in Rio Linda, after she delivered her by C-section in 2016. Campbell said you could see in her face how disoriented she was after the birth. She said she’s preferred her two home births since and hopes to deliver her fourth child at home in February.

Renée C. Byer

The penultimate intervention was a conversation during which her doctor said they would have to break her baby’s collarbone if she continued with labor. It scared her. She wanted what she called a natural birth, but she relented and underwent the surgery.

When she saw an obstetrician nearly three years later for her second child, she said the doctor sowed worry about the complications that could occur with a VBAC. The obstetrician also plugged Campbell’s information into a “VBAC calculator.” This version of the calculator — which is now considered outdated — factored in race when considering whether a patient was a good VBAC candidate.

When the doctor marked Campbell’s race as Black, the calculator gave her bad odds for a successful trial of labor.

“I was like, ‘Say that I’m Mexican,’” Campbell said. The doctor had assumed her race based on her appearance — she is mixed-race, and her mother is Latina. The doctor put in a new race, and Campbell’s odds of success jumped up.

Ultimately, she gave birth vaginally in a birth center, under Wisner’s care.

Campbell believes the standard health care system was rigged to steer her toward surgery.

The data suggest she’s right.

Destinee Campbell holds a sonogram of her baby, who is due in February, while standing with her family in Rio Linda earlier this month. “I’m a little bit nervous because I’m having some high blood pressure spikes so that means I’m probably going to end up in the hospital and I’m nervous they are going to push a cesarean instead of allowing me just to VBAC with this baby,” said Campbell.

Renée C. Byer

DOCTORS SOMETIMES DEFAULT TO FEAR ABOUT VBAC

Statewide, out of 683,475 C-section births captured in National Center for Health Statistics data between 2017 and 2021, nearly half — 47% — were repeat cesareans.

Doctors may not mention the scarce access to VBAC in conversations with patients leading up to their first C-sections. Katie Swedo, who is raising three children she delivered by VBAC, does not recall her obstetrician ever relaying how her C-section would affect her future. She gave birth for the first time at 19 — surgically, as her doctor recommended — to a child she placed for adoption. As it came time for her to start her own family, she learned that in a hospital setting, “They immediately label you as high-risk.”

That lingering sense of hazard often colors the way providers communicate with their patients, and those conversations shape health outcomes, said OB-GYN Annette Fineberg. “There’s people who are very insistent” that they want to pursue a VBAC, she said. “But there’s also a lot of people who just want your advice, and if you make them afraid, they’re never gonna go for it.”

Sometimes, doctors scare their patients about post-surgery vaginal birth, said Kairis Joy Chiaji. But Chiaji, a doula based in the capital region, said she very often encounters clients whose doctors never discussed it with them in the first place: The repeat C-section was a given.

That is partly due to a small but serious danger to people who try standard labor after a cesarean.

“The risk of uterine rupture is about one in 200,” Fineberg said. “If you have a uterine rupture, it’s an emergency, and you need to go to C-section.” Usually, the baby is fine, but if the parent does have a uterine rupture, there is up to a 6% chance of a perinatal death. For each individual, the risk to the baby, then, “is 1 in 2,000. So it’s low, but it’s not zero.”

The fear of VBAC is also due to something completely unrelated to maternal or infant health: The low — but not zero — risk that a doctor or hospital might get sued.

Katie Swedo, 35, whose first birth at age 19 was a C-section, has her hands full now with her three children, 10-day old Winona, Emrys, 1, and Seneca, 3, in Fair Oaks on earlier this month. Her first child was given up for adoption but the others were all born VBAC. Swedo doesn’t recall her obstetrician ever mentioning the impact a non-emergency C-section would have on her future births.

Renée C. Byer

WHY ARE HEALTH CARE PROVIDERS NERVOUS ABOUT VBAC?

Some VBAC hospital bans are tied to the institution’s lack of a 24/7 anesthesiologist. The explanation is simple: Having a C-section increases the chance of uterine rupture in a subsequent vaginal birth, and a uterine rupture requires emergency surgery, which requires anesthesia.

Relatedly, in 1999, the American College of Gynecologists and Obstetricians recommended that an anesthesiologist should be immediately available to tend to any patient attempting a VBAC.

But that recommendation may not have been solely based on the well-being of people giving birth.

“Concerns over liability have a major impact on the willingness of physicians and healthcare institutions to offer trial of labor,” says the 2010 National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference Statement on Vaginal Birth After Cesarean. “These concerns derive from the perception that catastrophic events associated with trial of labor could lead to compensable claims with large verdicts or settlements for fetal/maternal injury — regardless of the adequacy of informed consent. Clearly, these medical malpractice issues affect practice patterns among healthcare providers and they played a role in the genesis of the ACOG’s 1999 ‘immediately available’ guideline.”

The interim CEO of the college, Christopher Zahn, disputed this. “It is inaccurate that medical malpractice issues played a role in ACOG’s clinical guidance or influenced ACOG’s recommendations on VBAC,” he said in a statement to The Bee. “The consensus recommendation was based on optimizing patient safety. … Issues of cost, including malpractice-related issues, were never a consideration.”

Still, the fear of liability is widely acknowledged. Fineberg and Zoe A. Tilton, who both worked as OB-GYNs in Sutter Medical Group, wrote in 2012 in the journal Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology that a scheduled C-section “takes far less time and carries less liability” than a vaginal birth, “even if there is an adverse outcome.”

The thinking goes that, generally, whatever happens after a C-section won’t spur damaging lawsuits, but a vaginal birth that ends badly could. That isn’t altogether wrong: In the 1990s, doctors and hospitals lost several high-profile lawsuits over devastating birth outcomes.

An Alabama mother won $600,000 from a hospital in the early ’90s after she suffered a uterine rupture and her daughter died — her doctor had encouraged a VBAC. In 1996, Baltimore’s Daily Record reported on a vaginal birth gone wrong for a mother who had two previous C-sections. Gregory C. Baumann wrote that she spent more than 11 hours in labor before requesting another cesarean. Her lawsuit alleged that the doctor delayed performing the surgery for too long, causing her baby’s developmental problems and leading to a uterine rupture and a hysterectomy. She and her husband won $593,000.

Later, the Houston Chronicle reported in September 1999 that a plaintiff settled for $1.05 million after a Texas mother had a VBAC and the child died. The Chronicle’s Ron Nissimov wrote, “The lawsuit alleged that hospitals and health management organizations have downplayed the risks associated with vaginal births for women with previous C-sections in order to try to save money.”

Such lawsuits contributed to physician squeamishness around women trying to give birth vaginally after uterine surgery. The settlements also helped form institutional policy and practices that forced women into these invasive procedures.

But the NIH consensus panels found there was a “low level of evidence for the requirement for ‘immediately available’ surgical and anesthesia personnel.” Though ACOG now recommends that a trial of labor after C-section “be attempted in facilities that can provide cesarean delivery for situations that are immediate threats to the life of the woman or the fetus,” the newer guidelines have made some allowances for facilities without 24/7 on-site surgical capabilities, as long as emergency surgery can happen quickly.

Still, the Practice Bulletin 205 repeatedly says that it may be appropriate for those lower-level facilities to refer VBAC patients to a hospital with more comprehensive services.

And hospital hypervigilance leaves rural Californians in particular with fewer options, as smaller hospitals may have an anesthesiologist on-call, but typically won’t have one on-site at all times.

Sutter Davis Hospital, too, followed ACOG’s “immediately available” recommendation, and, for a time, banned VBACs in the facility. No anesthesiologist was in the building when Annette Fineberg made a decision that would ensnare her in months of controversy around 2009.

Fineberg looked at her patient’s chart and saw her history. It would have been wrong, she thought — it would have been bad health care — to perform a C-section. She talked to the patient, who was in active labor and went on to deliver a perfectly healthy baby in a perfectly healthy vaginal birth.

The patient had received the proper care. But Fineberg had broken the rules.

And she would face the consequences.

VBAC BANS CAN BE OVERTURNED

As Fineberg has written in multiple articles, Sutter Davis Hospital offered VBAC for decades before hospital administrators banned the practice in 2002, citing liability concerns.

She started working there in 2003, the year after the ban went into effect. At first, she didn’t make much of the practice.

Then, she said, “Around 2006 is when people started really realizing, ‘Oh my god, we have all these C-sections we’re doing. We have so many more placental complications, so many more hysterectomies, so many more really serious problems.’”

She also, like Johnson, said she saw some of the absurdity. “We would have patients who had had two VBACs, and then we still had to do a C-section for them,” she said. “Oh my god, yeah — we had to. It was so wrong.”

A particular patient pushed her into a mutiny around 2009. “She was very heavy; she was premature, like 36 weeks, so there’s a small baby; she’d already had two VBACs; and she came in in really active labor,” Fineberg said. “And I was like, ‘I’m not gonna do a C-section on this woman. She’s huge. The risks for her for a C-section are way higher than the theoretical risks for a VBAC.’”

Fineberg oversaw the woman’s vaginal delivery. The baby and the mother were healthy.

She said the administrative hurdles, however, were “just insanity.”

The paperwork she was obliged to do after breaking the rules took months; the hospital admonished her.

She decided the policy was so counter to good medicine that she rallied her colleagues to reverse the ban. The process took years of meetings and negotiations with administrators and doctors; it was, she said, “an epic battle.”

But in the end, they all agreed that they could accept low-risk patients who wanted to try a vaginal birth in the hospital. A representative for the hospital confirmed that the ban was lifted in 2014. Anesthesiologists were always on-call for other emergencies, but since the shift, the on-call person comes in for every woman attempting to have a non-surgical birth after a C-section, in case of a uterine rupture. An obstetrician would be on-site as well.

Fineberg said the new policy created an inconvenience for the doctors, and better health care for the patients.

She has since left the hospital, but Fineberg said the facility did around 600 VBACs over nine years after ending the ban. A few times, the anesthesiologist who was waiting around in the hospital stepped in when women suffered uterine ruptures and needed emergency surgery.

No babies were injured, which was the biggest liability fear.

“You could have a pretty big lawsuit if you have an injured baby,” Fineberg said. “That could cost millions of dollars.”

The fear of a lawsuit was, very explicitly, what forced Krystina Rossfeld into the operating room in 2018 as her doctor told her she couldn’t leave the hospital.

VBAC Facts founder Jen Kamel likes to say, “When we talk about reducing (medical providers’) perceived liability risks, what we’re really doing is just pushing that risk into the bodies of birthing people.”

Rossfeld knows that viscerally.

Anailicia Bates, 4, left, looks up at her mom Destinee Campbell, holding daughter Marielena Bates, 2, and dad Larry Bates, embracing daughter Nayelieden Bates, 6, at their home in Rio Linda on Aug. 11. Nayelieden was born by C-section but Campbell’s two other children were born VBAC.

Renée C. Byer

‘I WAS GOING TO TRY A VAGINAL DELIVERY.’

Rossfeld was just shy of 21 when she gave birth the first time, in 2008. The doctor had given her Pitocin, which induces labor and, as it does so, makes contractions much more intense. The pain was excruciating.

Then the doctor told her that her baby was in danger, and they should go ahead with a cesarean. She acquiesced.

“I was naive,” Rossfeld said. “It was a combination of being young and being uneducated, and believing the doctors. And that led to a C-section.”

During the surgery, the drugs made her vomit.

Health care providers recommend that an incision should have at least two years to heal before the start of the next pregnancy. Four years later, Rossfeld was pregnant again, and she delivered her daughter vaginally. In 2016, after laboring with her third child for hours, she opted for a second C-section.

She became pregnant with her fourth child, due in 2018. She said she discussed vaginal birth with her obstetrician early on, and the doctor supported her desire to try to avoid another surgery.

She hadn’t had a C-section for two years. Because she underwent two prior cesareans, the likelihood of complications from a vaginal birth was higher (though, so too were the risks of a third surgery — and she wanted to have more children).

“They needed to say what they needed to say about risks and stuff, but they were like, ‘It’s your choice if you want to do it,’” she recalled. “They were on board with it. They had no issue, or at least they did not let me know of any issues.”

She said she discussed the VBAC plan with her doctor multiple times. She didn’t want to recover from the surgery, and furthermore, a VBAC was her best chance to have safer births in the future.

“Up until the day of delivery,” Rossfeld said, “I understood that that was gonna happen: I was going to try a vaginal delivery.”

On the day she went into labor, though, a different doctor met her at Kaiser Modesto. And that doctor had other ideas.

Rossfeld and her husband at the time, Corey Logan, both remember the obstetrician walking into the room and saying she knew what Rossfeld wanted, and she wasn’t going to let it happen.

AN EFFORT ‘TO COERCE’

A representative for Kaiser Permanente, Jordan Scott, said in a statement, “We make every attempt to honor the patient’s birth plan while still ensuring the health and safety of the patient and her baby.” Scott noted that Kaiser hospitals have some of the “highest rates of successful and safe VBAC.”

So, in accordance with the hospital system’s rules, Kaiser Modesto didn’t have a VBAC ban. But Rossfeld and Logan said the doctor on call told them she wouldn’t “allow” a vaginal delivery.

Doctors are allowed to make those personal decisions, and they, too, broaden or conscribe women’s options. Maybe a woman plans to deliver at a hospital that allows VBAC, but if the doctor on call when she goes into labor thinks it’s too risky — for the baby, for the parent or for their own career — then that woman’s choice becomes irrelevant.

Rossfeld said her experience delivering her fourth child felt like a double-cross. She remembered that in the tiny hospital room, the doctor told her, “I’m not gonna let you deliver vaginally. If something happens, it’s a liability. It’s my license.”

Rossfeld was in the throes of labor, but she was defiant at first. Fine, she told the doctor, she would just go to a different hospital.

And then, Rossfeld said, the doctor told her she was not allowed to leave.

Looking back, she viewed it as an effort “to coerce me into agreeing to having a C-section against my will.”

She gave in, feeling as though she had no other choice. They shaved her, and wheeled her into the operating room just before midnight. The anesthesia made her body shake with cold.

Rossfeld was numb, so she couldn’t feel the knife.

But as the doctor sliced into her, she wept.