California schools respond to students' fears of Trump immigration policies

This article was produced as a project of the USC Center for Health Journalism National Fellowship.

Oher stories in the series include:

Therapy used for U.S. veterans finds success among traumatized immigrants

Undocumented 'Dreamers' from across California come together to discuss their mental and emotional health. Jenny Manrique

SAN FRANCISCO, Calif. - On a recent Saturday, some 150 students from various Bay Area high schools spent the day talking about one of their biggest concerns: their emotional health in the age of Donald Trump.

The students, most of whom were undocumented, others with a relative without papers, were at the annual “High School DREAMers Unite!” event, held at Sequoia High School (SHS) in Redwood City, 30 miles south of San Francisco.

“We all have to learn to deal with emotions, especially at this time of so much anger when many feel they want to leave the United States,” said Marvin, a 16-year-old Salvadoran who is part of the Dreamer’s Club at SHS. Latinos make up nearly 60 percent of the student population at his school, with an estimated one undocumented student per classroom.

In the first 100 days of the Trump administration, immigration detentions increased by 38 percent over the same period in the previous year, according to a recent report by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). Of the 41,318 arrested, 26 percent (10,845 people) had no criminal record. This means families with undocumented people do not feel safe – even in a space as traditionally sacred as a school.

“We feel vulnerable but we should not live in fear because then the government will just do what it wants while we stay in the shadows,” Maycol said.

In this new climate, California is shielding itself against Trump’s policies. According to the Department of Education, 57 school districts in the state – out of a total 330 – have tried to quell the fears of undocumented families by declaring themselves “safe havens” for immigrant children. That makes it the state with the highest number of resolutions in the country.

Aware of the fear and trauma in children triggered by personal circumstances and national policies, schools in California are offering alternative therapies to deal with these emotions.

Meditation and sharing

Submitted Photo / Teonna Woolford, a sickle cell disease patient in Baltimore, has been unable to afford fertility preservation for years. She started a non-profit to provide financial grants for patients who need fertility care, and advocates for more awareness about the effects of sickle cell on patients’ family planning and sexual health.

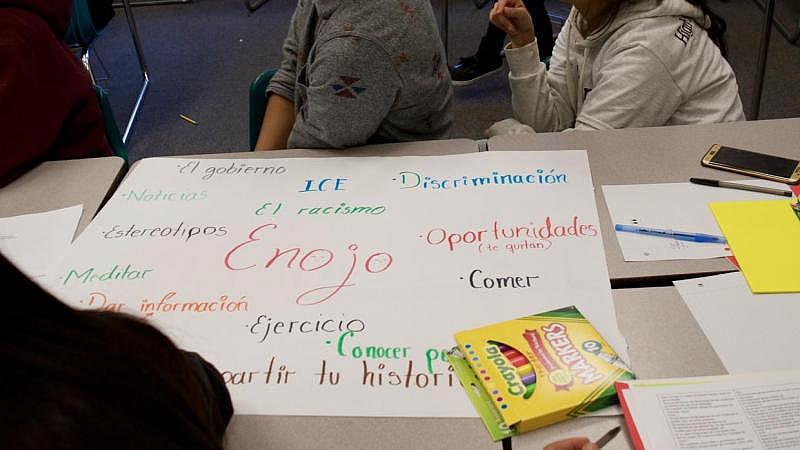

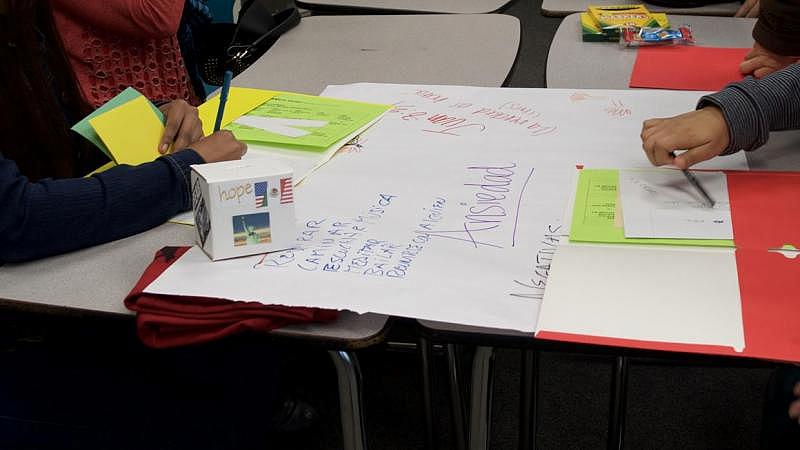

At the Redwood City event, children were encouraged to portray their emotions through art. Divided into groups, some painted the U.S.-Mexico border and wrote the word “fear”; others drew an ICE truck and a child hiding behind the door of a house; still others wrote words like “anxiety,” “anger” or “discrimination.”

They also shared how they deal with these emotions and lead normal lives. “I get relief doing martial arts or hugging my dog,” said Sara, 14. “I take art classes here at school,” said Luna, 16. Diego, 15, said he does meditation in the mornings or when he’s about to take a test. “With my teammates we are using the Calm app,” he said, referring to an application that facilitates meditation.

Judy Romero, a psychologist and director of Sequoia High School’s Youth Resource Center, said it’s the third year meditation is being implemented at the school. “Teachers apply it in their classes,” she said.

Many teachers are astonished to hear the students’ painful stories of arrival in the country, said Romero, adding it’s seen as a “miracle” that those students can focus at all on their classes.

Most schools in San Mateo County, which encompasses Redwood City, have at least one or two counselors. SHS has three psychologists and five practitioners who offer free therapy for as long as a student needs it regardless of their immigration status.

“Many young people have suffered not only trauma in their countries but their parents at some point left them with other relatives, grandparents or uncles, to come here. The reunion here is a challenge because there is a lot of resentment, they feel strange,” explained Romero. Some children live in mixed-status families, where some members are undocumented, others have green cards or DACA, and others are citizens. “They experience confused feelings that can affect family dynamics because of jealousy, anxiety, or guilt. These workshops are very useful for them because they get to know other families in the same situation.”

In the United States, undocumented youth are granted equal rights to K-12 public education under a 1982 Supreme Court decision. Privacy laws also protect students by prohibiting schools from handing over information to immigration authorities.

But in late March, civil rights groups asked the California Attorney General to investigate dozens of school districts throughout the state that were requiring parents to provide child social security numbers, citizenship status, and other sensitive information when they entered the country.

Demanding that families provide such information can cause a “chilling effect,” deterring parents from enrolling children in school, according to the San Francisco Bay Civil Rights Lawyers Area and California Rural Legal Assistance.

With bullying on the rise against Latino children in schools, Dreamer Clubs are becoming more popular as they provide immigrants with a greater sense of protection.

“The club is a response to the frustration many undocumented students encountered in their transition to college,” said teacher and founder Jane Slater, who has been working in the school for 25 years. The weekly club was formed nine years ago and has about 40 active members.

There are several annual events, such as a fundraising dinner and the Dreamers conference, which includes a workshop on emotions.

More and more members come out of the shadows and tell their personal stories in conferences, local churches and of course the school. “It has been very cathartic,” Slater added.

The role adults play

Most school districts in California employ the Cognitive Behavioral Intervention for School Trauma (CBITS) program designed to reduce the symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in children. The intervention model seeks to involve families, teachers, guardians, coaches, and even school administrators in understanding that there are “highly sensitive” cultural elements in play in these children’s narratives. Today it is implemented in 14 states nationwide.

“Teachers have become a crucial component for the emotional support of kids especially when parents are busy doing three jobs,” said Melanie Wartenberg, director of mental health services at the East Bay Agency for Children (EBAC), who has been working for eight years with K-12 students in 16 schools in Alameda County, east of San Francisco. Through MediCAL (Obamacare in California), EBAC provides 23 therapists to these schools, including six who speak Spanish.

“We work with adults to understand what adverse childhood experiences are and the kind of neurological impact trauma has on children,” she said.

Many have difficulty regulating their emotions, are easily upset or hyperactive in the classroom and lack motivation to learn because they suffer from PTSD as a result of their migration experience. “Some experience disassociation when they hear the police patrol or the news, a feeling that has escalated due to the current political climate.”

Alameda County, which includes Oakland, provided $2.5 million in mental health services for the period 2016-2018. Yet Waltenberg said there are not enough bilingual practitioners.

According to the California Department of Education, total funding for grades K-12 in the period 2016-2017, including state, local and federal funds, is $88.3 billion. Of this, 10 percent comes from the federal budget. It’s unknown how much money goes specifically to mental health services.

Alicia Gallardo, a 37-year-old family therapy graduate whose own family emigrated from El Salvador in the 1970s, works for EBAC in a “Newcomers” program for immigrants or children of immigrants from El Salvador and Guatemala. She says some children do not consider crossing the border a traumatic experience. “Walking for six weeks, arriving alone separated from their families, going hungry and thirsty, are facts that they view as natural because they have developed very strong survival strategies to defend themselves,” she said.

Gallardo assists unaccompanied minors detained by immigration officers and placed in transition homes under the Refugee Resettlement Office program. Some of them have been reunited with their parents or another reliable adult and go to school while they wait for a court hearing. An estimated 400 such unaccompanied minors are enrolled in the Oakland School District.

Gallardo said there are several challenges. “As they have to face the immigration court, we do role-playing games to practice how they will respond to the judge’s questions and regain control of their lives.”

In the hearings, children tell of the traumas they witnessed or experienced, such as abuse, violence, or terrorism. This leaves many open wounds that have to be treated in therapy.

“It’s a very stressful situation, especially because the courts do not have the responsibility to offer them any legal support and much less mental help,” she said.

Soccer and art

Axel, 18, left Guatemala three years ago and traveled to Mexico with his younger sister. Once on American soil, they were left alone by a coyote, without money or a way to communicate. “He left us with a backpack and some clothes,” Axel said. “We did not know what to do, to turn ourselves in was the only way.”

According to his account, he and his sister spent 15 days in a “cooler” in Texas, as ICE transitional detention centers are known, and ended up in a home in Arizona until they reunited with their father in California a month later.

Axel now studies at Oakland International High School and is about to graduate. “I get counseling twice a week. I’m one of those people who gets angry very easy and at some point I had an altercation that turned into a fight and I did not want to go back to that. Here I feel free to express myself,” Axel told Univision.

He said that the Soccer without Borders program, established in this secondary school in 2008, has been the most beneficial. “Through soccer, I speak to a lot of people who do not speak Spanish, so I learn from them and their customs. They are very supportive even outside of school,” he added.

Physical exercise helps the students cope with trauma, and belonging to a team gives them a sense of family, breaking the language barrier, said Lauren Markham, coordinator of Community School Programs at the school. She says there are almost 100 unaccompanied minors in the school and 30 percent of the students are undocumented.

“In addition to sports, collective therapy is very common. We have circles of restorative justice to resolve conflicts, groups for the development of masculinity, feminine solidarity and cultural integration. Since most are Latino, we have five groups in Spanish,” Markham said.

The county sponsors up to eight therapy sessions per student, and counseling promotes extracurricular activities. There are 10 counselors in charge; two work full-time and are bilingual.

Estephanie Noriega is a counselor through Family Counseling Services, one of the agencies responsible for handling cases of unaccompanied minors in Alameda County. She sees between 15 and 20 children a week.

“We do exercises with breathing techniques. We give them stress balls, puzzles, we have them write and color, so they can describe how they are feeling,” she said.

Noriega said that when Trump was elected, teachers encouraged students to draw and paint. Soon, the school yard was filled with posters drawn by children. “They drew lots of flowers and butterflies, inspiring phrases such as ‘we’re not going to drop,’ but also rude messages.”

Sanctuary schools

In interviews with Univision, children mentioned the words “fear” and “sanctuary” most often—the former to describe their emotions and the latter to describe what makes them feel protected in California. Since October 2015, all undocumented children in the state are covered by MediCal. At the beginning of April, the Senate also passed a state bill to convert the entire territory into a sanctuary. That’s waiting for a vote in the House.

Los Angeles is among 57 school districts is the state that have been declared sanctuaries. There, about 200,000 students are either immigrants or members of mixed-status families. On May 9, the Los Angeles school board approved a set of policies including that no immigration officer will be allowed to enter schools without authorization from the superintendent of each institution and only after consultation with the district attorneys.

That was a response to the February arrest of Rómulo Avelica-González, taken by ICE after dropping off one of his children at school while another child was waiting for him in the car.

“We train crisis counselors at all schools to serve children and families facing trauma,” said Pia Escudero, the Los Angeles Unified School District Director of Mental Health, who oversees nearly 300 professionals including social workers, psychiatrists and clinical psychologists.

“Since January 2017, we have had workshops for families to learn how to make a safety plan if there is a raid, where they are going to meet, who to call. The idea is to normalize as much as possible the situation so that children continue to go to school and focus on studying,” added Escudero.

In Los Angeles, each school has its own autonomous budget to hire social workers, nurses, or mental health service teams for children. There are also 14 mental health clinics and seven wellness centers, where children can receive counseling or therapy, regardless of their immigration status.

The Fresno Unified School District also recently took steps in a similar direction. On March 8, it passed a resolution stating that schools should not take immigration status into account, meaning they do not ask for social security numbers. The resolution includes a strict policy that prevents ICE agents from entering schools or addressing a student without the consent of parents or guardians.

Of 74,000 children in 80 Fresno schools, an estimated one-in-five are from mixed-status families. For them, the district provides 60 school psychologists, including 10 who are bilingual.

“Today we help them submit applications to DACA and to universities, because they fear the government will keep their data. The board supports them,” said Claudia Cazares, trustee of the Fresno School District.

The cities of Sacramento, Oakland, San Francisco, San Bernardino, Stockton, San Jose, Riverside, Long Beach, Santa Ana, San Diego and Fremont passed similar resolutions this year.

“Know your rights” workshops have also been held in various parts of California with support from the Mexican Consulate.

“The important thing is to tell the children that the trauma can be overcome,” says therapist Noriega. “They are not alone. The school system supports them.”

The parents of the minors mentioned in this article only authorized the use of their first names.

[This story was originally published by Univision.]

[Photos by Jenny Manrique/Univision.]