Leangela Frazier remembers when she no longer had a stable place to live. The 39-year-old single mother of four had left a difficult relationship and was bouncing between couches. “I always kept a roof over my kids’ head but after that situation, I had to take all four of my kids and go,” Frazier says.

A friend pointed her to Women’s Empowerment, the Sacramento nonprofit that helps women experiencing homelessness rebuild their lives. After attending an orientation, she was approved for the program and committed to nine weeks of intensive classes. That difficult relationship had become abusive and left Frazier essentially homeless if not for Women’s Empowerment.

In 2023, California police fielded more than 160,000 calls related to domestic violence — about 18 calls every hour — according to the Public Policy Institute of California. That is down from 2001, when police responded to more than 198,000 calls, or nearly 23 every hour. However, the number of domestic violence incidents has remained between 18 and 19 calls per hour since 2017.

In Sacramento, police fielded 1,891 domestic violence-related calls in 2020, which jumped to 2,091 in 2021 during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. By 2023, the number had nearly doubled again to 4,971 before dipping slightly to 4,802 in 2024, according to the California Department of Justice.

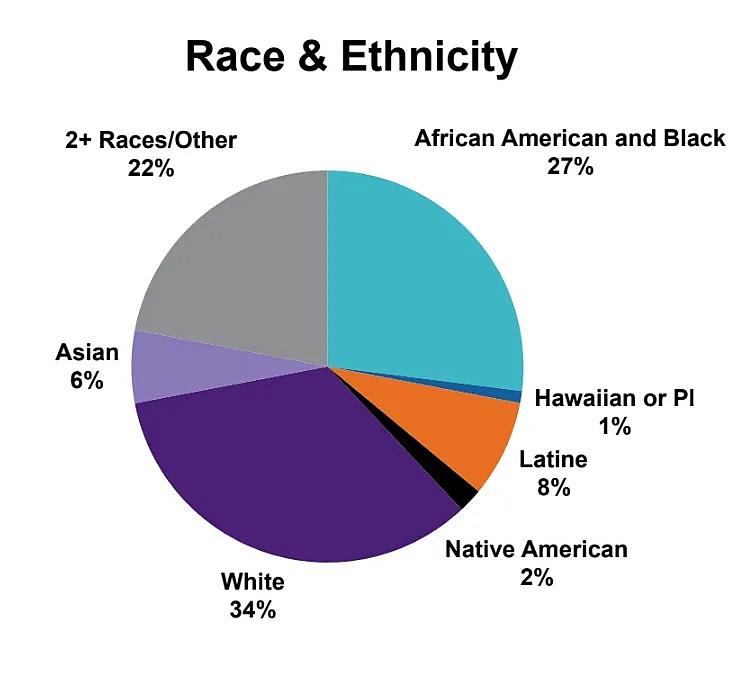

Unfortunately, many Black women become homeless and develop lasting health issues after experiencing domestic violence.

Advocates in Sacramento say domestic violence is one of the leading drivers of homelessness for women, particularly Black women, who already face disproportionate barriers in housing and health care. Women leaving abusive partners often have few safe places to go, and the trauma compounds when children are involved.

Julie Seewald Bornhoeft, chief strategy and sustainability officer for WEAVE Inc., explained that every woman who comes into the organization’s safe house is experiencing homelessness in some form — whether staying in a shelter, lacking stable housing, or fleeing immediate danger. Many still technically have a home when they reach out, but the violence inside makes it unsafe.

She says the urgency often lies in how quickly survivors must find new housing or face homelessness. To meet that need, WEAVE provides an emergency shelter, transitional housing, and nine units of permanent supportive housing. The overlap between domestic violence and homelessness, Bornhoeft says, is undeniable.

One of the biggest barriers is financial stress and abuse. Nearly every person entering WEAVE’s safe house has experienced it. Sometimes that means job loss because injuries prevented them from working, or harassment forced them to leave. Employers may fail to recognize the abuse and provide protections, leaving women with gaps in employment that make it harder to find work.

Financial abuse also can take the form of coerced debt. Survivors often are pressured into taking out credit in their names, only to have abusers run up balances that go unpaid. In some cases, credit is taken out in a victim’s name without their knowledge. Either way, the damage to credit makes securing housing nearly impossible. Even women who remain employed may not have access to family finances, leaving them with virtually nothing when they escape.

Beyond finances, survivors often face physical injuries, long-term disabilities or preexisting conditions that add another layer of vulnerability. Abusers also use isolation as a form of control, cutting off women from family, friends or faith communities. Without those support systems, many survivors feel they have nowhere to turn.

Bornhoeft emphasized that survivors of domestic violence are resilient, often raising and protecting children while enduring unpredictable violence. But the barriers they face after leaving are immense. For Black women, those barriers are compounded by racism, intergenerational trauma and systemic inequities that create an additional layer of vulnerability to homelessness.