Caught In The Crosshairs: Gun Violence Takes Its Toll On Black Community

The story was originally published in The Observer with support from our 2024 California Health Equity Impact Fund.

(From left) Louise Jedkins-Tyler, Kejion Starkes’ great-aunt, with his mother, Tasha Cousins, and Kejion’s younger sibling King Pope, 14, at the site where Starkes was shot and killed Feb. 17.

Louis Bryant III, OBSERVER.

Kejion Starkes was driving from an ex-girlfriend’s house in Natomas in February when someone fired a gunshot into his car, causing him to crash into the fence of a nearby school. Starkes was killed around the corner from where his ex-girlfriend lives, according to Starkes’ mother, Tasha Cousins.

Starkes, 26, never owned a gun. Nor was he in a gang. He was a signed music artist and loving father, brother and son, Cousins says.

Cousins never thought her family would fall victim to gun violence. The greater fear was that her son would take his own life during his teens as he struggled with his mental health.

“The last five years of his life he was doing amazing,” Cousins says. “He told me that he didn’t want to die anymore. He said ‘I want to live.’ All his friends were dying around him and he was right at home on the couch.”

Starkes had just given his new girlfriend a Valentine’s Day basket, which he displayed on social media about 10 hours before he was killed.

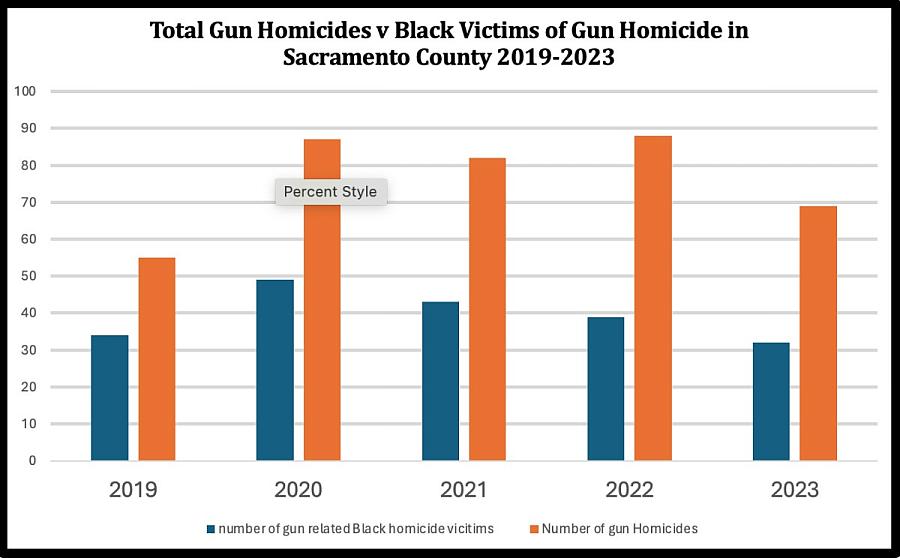

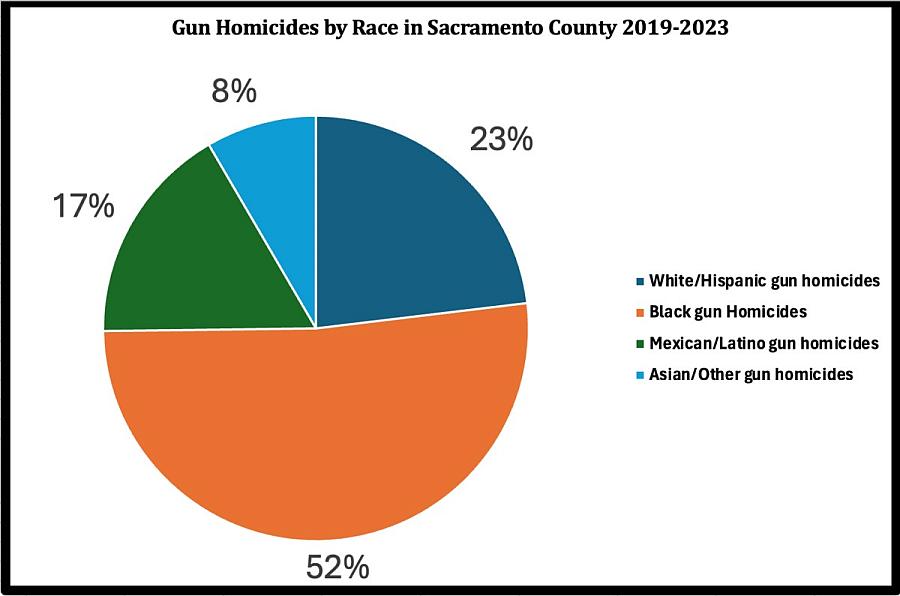

His death reflects the devastating problem facing Sacramento’s African American community when it comes to gun violence. While Black people make up roughly 12.6% of Sacramento County’s population, they account for about 52% of all gun-related deaths from 2019 to 2023, according to an OBSERVER analysis of coroner data.

The number of gun homicides in Sacramento County from 2019-2023 shows a disproportionate number of Black victims.

Graphic by Robert J. Hansen, OBSERVER

In the county’s 381 gun-related homicides from 2019 to 2023, 197 victims were Black.

Among them are 10-year-old Keith “KJ” Frierson, who was shot and killed Dec. 30 by another 10-year-old with a stolen gun retrieved from his father’s car.

The youth’s dad, Arkete Davis, 53, pleaded not guilty to six charges, including child endangerment, being a felon in possession of a firearm and destruction of evidence. The 10-year-old shooter was released to his mother.

Inderkum football coach Gregory Najee Grimes was shot in front of a downtown nightclub July 4, 2022, three months after the K Street shooting that killed six and injured 12.

The suspect in Grimes’ slaying, Tahje Michael, was at large for 19 months until Sacramento police, collaborating with the U.S. Marshals Service and the TV show “America’s Most Wanted,” apprehended him in February.

Deborah Lewis-Grimes, the slain man’s mother, told The OBSERVER that when she received the call that Michael had been apprehended, all she could tell the detective was “Thank you, thank you, thank you.”

“I couldn’t even formulate anything in my mind to go beyond gratitude,” Lewis-Grimes says.

Percentage of Sacramento County gun homicide victims by race from 2019-2023.

Graphic by Robert J. Hansen, OBSERVER

She credits all the members of law enforcement who worked in apprehending Michael and says getting their family’s story on national TV was crucial.

Another Black man who died from gun violence in 2023, 21-year-old Ben Sapp, was shot and killed in Sacramento’s Greenhaven neighborhood Dec. 7.

Police responded around 12:51 p.m. to the 6100 block of Riverside Boulevard after reports of a shooting. Sapp was found and transported to a nearby hospital, where he was pronounced dead.

An arrest has yet to be made in the case.

“Our detectives are still actively investigating this case and following up on leads,” a police department spokesperson told The OBSERVER on Monday.

Slow Justice And Eroding Resources

Johntaya Alexander, 21, was one of six killed in the K Street shooting April 3, 2022.

Robert J. Hansen, OBSERVER

No arrests have been made in Kejion Starkes’ killing either.

There’s a large disparity in unsolved homicides of Black people, according to FBI data.

From 2018-2020, for white and Asian homicide victims, a suspect remains unknown in roughly 22% of the more than 23,000 homicides during that time.

For Black victims, a suspect remains unknown, or an arrest has not been made, in 42.5% of the nearly 30,000 homicides reported during that period.

A homicide with a Black victim is nearly twice as likely not to result in an arrest than one involving a white, Native or Asian victim.

That disparity in closure rates explains why so many Black people are victims of gun violence, says DeVone Boggan, founder and CEO of Advance Peace. “Gun violence begets gun violence.”

Boggan began fighting against gun violence in Richmond in 2005 and is a national authority on urban gun violence intervention and prevention.

Advance Peace uses street outreach workers as violence interrupters and adult mentors to support the decision making and life chances of those at the center of urban gun violence.

Richmond has experienced an 82% overall reduction in total shootings involving death or injury since Advance Peace’s inception in 2007.

Advance Peace did work in Sacramento from 2018-2021. In 2018 and 2019, the city experienced no gun deaths of anyone under the age of 18.

Boggan says the program ended in Sacramento for political reasons.

“The men that we have doing the work [being] formerly incarcerated and all that,” Boggan says. “I think the city didn’t like the look of it.”

Boggan says the disparity in Black victims of gun violence in Sacramento is similar to other cities that endure the same kind of regular violence. “The victims and perpetrators are often young men and boys of color,” Boggan says. “It’s unacceptable and it doesn’t have to be this way.”

Boggan says society needs to find a way to get stolen guns off the streets. “Most of these guns finding their way to the communities are illegal and are getting into the hands of folks that shouldn’t have them.”

The gun that killed little KJ Frierson was stolen and in the possession of a felon who was not permitted to own a firearm.

Berry Accius, founder of Voice of the Youth, and activist Freddie Dearborn have worked for years to reduce gun violence in Sacramento.

In April 2022, Accius led a march against gun violence days after the K Street shooting, Sacramento’s deadliest.

“Enough is enough,” Accius said at the time. “Let’s hold each other accountable.”

Gun violence rose in Sacramento, Accius says, because it did not invest in job creation and community youth programs such as Advance Peace. “We still have not reached those who are committed to saying, ‘We must end gun violence in our community,’” he says.

In total, six people died from the gun violence of the K Street shooting and four of them were Black.

The three suspects, all of whom remain on trial, also are Black and likely will spend most, if not all, of the rest of their lives in prison.

Dearborn, a change maker with Advance Peace, says something is needed to deter young people from gun violence. “I’d rather be judged by 12 than carried by six,” is the mentality of many young people, Dearborn says. He says he and Accius put their lives in danger every day.

“We are only peacekeepers,” Dearborn says. “Even when someone is harmed and gears violence toward us, our mentality still has to be peacekeepers.”

Accius says guns are much more available to youth than they were in the 1990s. He says the uptick of guns in our community, particularly in the hands of young people, during COVID-19 is overlooked and that it negatively changed the tide of gun violence locally.

“[Reducing] gun violence for us is taking away the guns from these young people and giving them other opportunities and different access to be able to wedge their way against feeling like they have to harm someone,” Accius says.

Legal Gun Ownership And Crimes

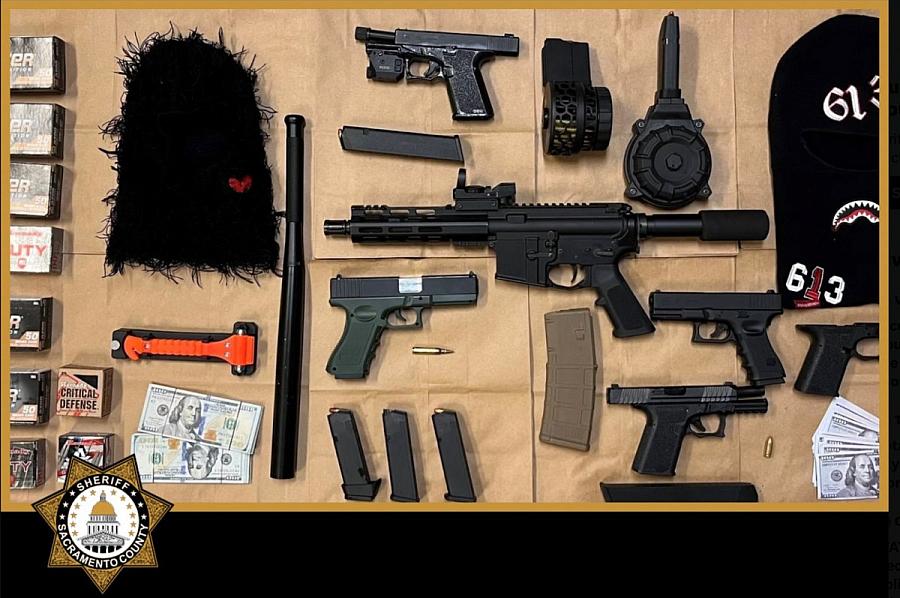

Guns recovered by Sacramento County deputies after the arrest of a 17-year-old April 3.

Sacramento County Sheriff’s Office

Approximately 4.2 million Californians legally own a total of 20 million firearms, including 9 million handguns, according to a 2018 UC Davis Health report.

Most legal owners purchased their last firearm from a retailer – often a handgun bought primarily for protection.

Blacks make up only 4% of legal gun owners in California.

Most guns used in killings are stolen, such as in KJ Frierson’s death.

Between 1996 and 2021, more than 5.2 million handguns and almost 2.9 million long guns were legally purchased in California. From 2010-2021, California law enforcement officers recovered 45,247 such guns from crime scenes, according to a 2024 UC Davis Health study.

“Tracking the movement of firearms from legal purchase to use in crimes can help inform prevention of firearm injuries and deaths,” explains Hannah S. Laqueur, an associate professor in the UC Davis Health department of emergency medicine and the study’s senior author.

One key finding in the study is that guns reported lost are three times more likely to be used in a crime, and stolen guns are almost nine times more likely to be used in a crime.

“Theft is an important source of crime guns, whether as the proximal source to the criminal possessor or simply as an important source of firearms entering the illicit market,” Laqueur says.