The children of Flint, ten years later

The story was originally published by Harvard Public Health as part of the 2023 Impact Fund for Reporting on Health Equity and Health Systems.

Dionna Brown calls herself a survivor of the Flint water crisis. Ten years ago, in April of 2014, the city switched its water supply to the Flint River. The move happened under an emergency manager, appointed by the state of Michigan to help the beleaguered city find its financial footing. But the river water was corrosive, awash with chloride from road salt runoff, and the city failed to add corrosion inhibitors to the water. Aging pipes began to leach iron and lead. The result was more than 100,000 residents being exposed to unsafe levels of lead in their drinking water.

Brown, then a junior in high school, remembers she needed to make a lot more effort to focus after the switch. “I was combining words and numbers a lot,” she says. “I had to work harder to just learn.” In 2018, a blood test revealed elevated levels of lead. Then came diagnoses of ADHD and dyslexia.

Brown didn’t let her learning challenges stop her: She graduated from Howard University and is on track to get a master’s degree next month. But like many Flint residents, she feels marked by the crisis. The most vulnerable people were and are children, thousands of whom live with the consequences of poor decisions made by politicians and health officials.

Yet, some positive developments have emerged. Community members have fought court battles to force the replacement of lead pipes. A coalition of public agencies, grassroots groups, and nonprofits—backed by federal, state, and foundation funding—has spent years building a creative care network to buffer some of the worst outcomes of the water crisis.

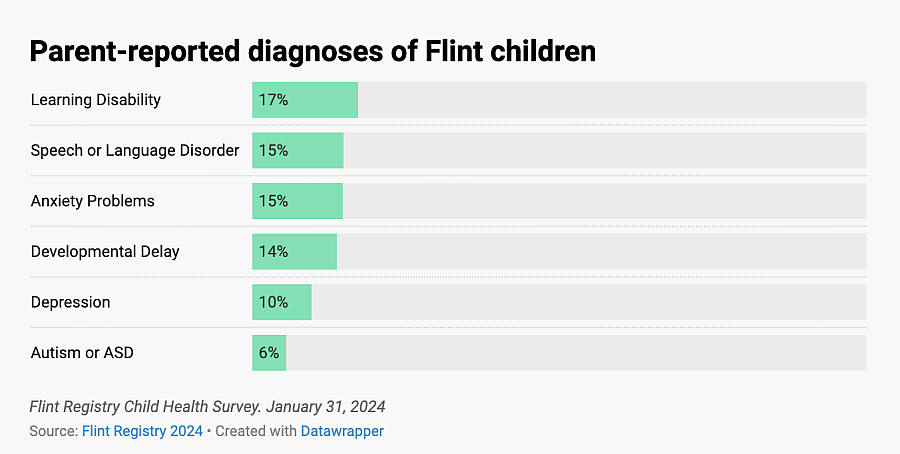

Still, the people of Flint continue to deal with ongoing physical, mental, and emotional challenges. Rates of depression exceed national averages for both children and adults. And almost half of the parents enrolled in the Flint Registry, which tracks the health of over 21,000 people affected by the water crisis, said that their children were living with behavioral problems as of 2022. These included attention issues, aggression, depression, hyperactivity, and trouble adapting. Many of these issues are worsened by ongoing stress from the years of crisis.

Dionna Brown, 24, outside her father’s car wash in Flint, Michigan in March. Brown grew up in Flint but did not get tested for lead poisoning until 2018. She found out that she had elevated lead levels; she is also coping with ADHD and dyslexia.

Photography by Kimberly Todd

Brown hugs her father, Dion Brown, Sr., after getting her car washed. Despite the struggles she experienced after Flint's water switch, she graduated from Howard University. Next month she expects to receive a master's degree in sociology from Wayne State University.

Photography by Kimberly Todd

Brandon Gilleylen still remembers mud-colored water spouting from his faucet a few weeks after the ill-fated water switch. “It was just shocking to see,” says the Flint native.

Almost immediately, residents complained of the water’s foul taste and smell. Many began to lose hair and break out in skin rashes. Not long after Gilleylen’s tap water turned brown, the city announced a boil-water notice because Flint’s water was found to contain fecal coliform, a sign of disease-causing pathogens. Boil-water notices for additional issues came soon after. Gilleylen and his wife, parents of a one-year-old child, duly followed directions and boiled the water they used to cook, bathe, and make baby formula.

What they wouldn’t know until more than a year later was that lead had leached from corroded water pipes. Boiling the water essentially concentrated the lead, and about 100,000 Flint residents had already been exposed—including the Gilleylens’ baby. Brandon’s wife, Ashaley Hart-Gilleylen, says she was racked with worry about their little girl. “It was really, really tough mentally, wondering what happened to her and how she’s going to be affected,” she says.

Brandon Gilleylen remembers standing in line for bottled water and feeling an “apocalyptic” sense of dread. “When is the water going to run out? Are we going to have any water left?” he would think. “We’re stuck with brown water coming out our faucets, and nobody’s listening to what we all have to say.”

Officials ignored residents who said the water was making them sick and flat-out rejected scientific evidence. In September 2015, researchers from Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University released results from a study of 252 Flint homes showing that 40 percent had water with elevated levels of lead, including one with levels twice what the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) considers to be hazardous waste. Still, state officials denied there was a serious risk.

Later that month, doctors at the city’s Hurley Medical Center announced that the percentage of children with elevated blood lead levels had doubled since 2013. The state again dismissed the science; a spokesperson described the research as “unfortunate” and mounting concerns as “near-hysteria.” But one day later, the city of Flint issued a lead warning; a week later, Genesee County, which contains Flint, declared a public health emergency.

For families like the Gilleylens, a waiting game ensued: Would they start to see signs of lead poisoning in their children? As the Gilleylens’ daughter neared kindergarten, she began throwing violent temper tantrums, which her father says were well beyond the norm for a child her age, and which they attributed to the effects of the lead poisoning.

Ashaley Hart-Gilleylen was pregnant by the time the city switched back to Detroit water in October 2015. A few months later, she would miscarry. “I know it was something to do with the lead,” she says.

By January of this year, roughly 15 percent of kids in the Flint Registry had been diagnosed with anxiety and 10 percent with depression. (The national rates for kids of similar ages are 9.4 percent for anxiety and 4.4 percent for depression.) “We’re alarmed” but not surprised, says Nicole Jones, an epidemiologist at Michigan State University and the registry’s codirector. “The things that we’re seeing are things that we expected to be associated not only with exposure to lead, but exposure to the trauma of an environmental crisis.”

A recent study points to the wider impact of the water crisis. Test scores in math dropped for 3rd through 8th graders across Flint following the crisis, while the number of K–12 students with special education needs rose by eight percent. The results showed little variation between kids living in homes with lead service lines and those without. Sam Trejo, a Princeton University sociologist and lead author of the study, says the findings point to the Flint water crisis “not just as the tragic events that led some kids to be exposed to more lead in their water … but instead as a broader kind of emergent crisis that affected an entire city.”

Trejo’s study is consistent with other research documenting how Flint remains caught up in the water crisis, with one in four residents suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder and struggling with ongoing physical health issues. Many still feel betrayed by local and state leadership.

Adults in the registry have fared even worse than kids when it comes to mental health, with more than a third diagnosed with depression. In addition, the data show many adults have chronic conditions like high blood pressure, which can be caused by lead exposure.

The community response was to wrap our children and families with goodness. What we’ve learned is that despite all the good stuff that we’ve been able to put in place, people continue to struggle.

Mona Hanna-Attisha, pediatrician

It’s an overcast Sunday in January on the Northside of Flint, but it’s warm inside the spacious sanctuary at Christ Fellowship Missionary Baptist Church. Rev. Allen C. Overton steps into the pulpit and begins his sermon. The pastor’s rolling baritone turns somber as he touches on the water crisis. “It’s a catastrophic tragedy that, 10 years later, I’m still on conference calls with my attorneys because every lead line has not been removed in this city.” Shouts of “Yes!” and “That’s right” ring out from the pews.

Back in the fall of 2014, Overton was watching television when General Motors announced it would stop using Flint water; the company was concerned that high levels of chloride could corrode its machinery. It would eventually come out that the failure to add corrosion inhibitors to the river water resulted not only in lead contamination but also in a reduction in chlorine levels, allowing other contaminants to flourish, including E. coli and Legionella bacteria. When more chlorine was added to fight bacteria, a buildup of trihalomethanes—disinfection byproducts linked to cancer—became yet another problem. At the time, though, state officials assured residents that even so, the water was acceptable for human consumption. Overton was shocked, and thought, “We got a problem.”

Rev. Allen C. Overton sits inside Flint's Christ Fellowship Missionary Baptist Church in March.

Photography by Kimberly Todd

Overton was a spokesperson for Concerned Pastors for Social Action, a Flint-area coalition of ministers. He began calling city and state offices to ask what was going on; he was repeatedly told the water was safe to drink. In 2016, Concerned Pastors became part of a group that brought a lawsuit against the city of Flint and the state of Michigan, which led to a settlement that included a commitment to replace all of the city’s lead and galvanized steel pipes.

Such pipes represent much of Flint’s infrastructure, given that Flint’s housing stock was largely in place by the late 1950s, says Richard Sadler, a medical geographer at Michigan State’s College of Human Medicine. Sadler led a 2017 study which mapped clusters of homes whose residents had high blood lead levels; one such cluster was located just a few blocks away from Overton’s church. Concerned Pastors has been back to court several times to force action, as Flint missed multiple court-ordered deadlines to replace its aging pipes. The city claims that 95 percent of the work is done, and now that the Biden Administration has set aside money to address the issue nationally, Overton feels optimistic. “I’m trusting and believing that the city administration is going to get it done this year,” he says.

Concerned Pastors is just one of the local groups that has rallied for Flint since the crisis began 10 years ago. Many local churches and nonprofits sprang into action, and groups like the Red Cross organized small armies of volunteers to staff water drives handing out bottled water to residents and to deliver clean water and fresh food to people who were homebound.

After-school programs, healthy-foods initiatives, and community health centers worked in tandem to stitch together a safety net for distressed families. The Genesee Health System, a public entity providing mental health services, used funds from a settlement to create what is now the Children’s Integrated Services Assessment Clinic, which tests local children for lead exposure and carries out neuropsychological assessments of children. Meanwhile, the Pediatric Public Health Initiative (PPHI), created by Michigan State and Hurley Children’s Hospital, targets care to focus on lessening the impacts of the water crisis through community programs, advocacy, training, and evaluation.

“The community response was to wrap our children and families with goodness,” says Mona Hanna-Attisha, the pediatrician whose announcement about the sharp jump in kids’ lead levels back in 2015 finally got officials to acknowledge the crisis. And yet, she says, the people of Flint continue to face enormous socioeconomic challenges. Hanna-Attisha is associate dean for public health at Michigan State’s College of Human Medicine and director of the PPHI. “What we’ve learned,” she says, “is that despite all the good stuff that we’ve been able to put in place, people continue to struggle.”

Hanna-Attisha is leading a new program called Rx Kids, which gives $1,500 prenatal cash payments to pregnant women in Flint and $500 per month for babies during their first year of life. The program launched in January with funding from a host of public and private sources. “We’re doing something that hasn’t been done before—we’re prescribing away poverty,” Hanna-Attisha says.

The task is daunting: The University of Michigan reports that nearly 70 percent of Flint kids still grow up in poverty. And almost half of registry adults say they have difficulty covering the cost of housing and food. Good nutrition is especially crucial, as calcium, iron, and vitamin C reduce the body’s absorption of lead.

A decade after the crisis, some lessons are clear, Hanna-Attisha says, citing, among others, a need “to invest in prevention, to invest in public health, to address inequities, and to respect science … and not have to rely on children to be resilient to overcome insurmountable challenges.”

Shaketta Brooks worries about those challenges. She and her nine-year-old son, sunny-natured and with a bright smile, are at the Flint Public Library, where they've been taking turns reading aloud from a book on Martin Luther King, Jr.

Her son was born premature just four months after Flint’s water switch. When women are exposed to lead before or during pregnancy, their risk of giving birth prematurely increases, as does the risk of miscarriage and having a low-birth-weight baby.

Brooks's son spent months in the neonatal intensive care unit at a local hospital. “They said he was underdeveloped,” she says, and he needed a blood transfusion. Children exposed to lead in the womb can suffer damage to the brain and nervous system, which can cause learning and behavior problems later on. He is among the more than 20 percent of kids with special-education or early-intervention plans in the Flint Registry.

Shaketta Brooks embraces her nine-year-old son on the Genesee Valley Trail in March. Brooks says she often walked here in 2014, the year the water crisis began.

Photography by Kimberly Todd

Brooks and her son walk in their neighborhood in Flint.

Photography by Kimberly Todd

Lead can be particularly harmful to young children, due to rapid growth of their bodies and brains. Because lead can damage the central nervous system, “it affects their cognition, it affects their learning, it affects their attention,” notes Jones, the Michigan State epidemiologist.

Brooks says her son can be hyperactive, so she signs him up for sports like basketball and boxing for exercise. But she’s “on eggshells” watching him run because of his asthma, another condition that can be linked to lead exposure.

Jones understands the fear: Lead exposure, she says, “is a lifelong concern."

On a quiet morning in a wooded corner of the city, the Flint River flowed serenely past Buick City, an old General Motors site, on its bendy route north toward Saginaw Bay. Marcell Simmons, 23, kayaks the river every summer. As a paddle guide for the Flint River Watershed Coalition, he educates people about the wildlife and plants that surround the river: bald eagles, great blue herons, and vegetation like water lilies and cattails, which Simmons eats from time to time just to prove to other paddlers these plants are edible.

He tries to foster respect for the river. “It was straight-up love for the city,” Simmons says about why he wanted the job. Barely a teen in 2014, he didn’t escape the fallout of the crisis. After the switch to Flint River water, his school performance took a hit. “I was a whole lot sharper prior to the water crisis,” says Simmons, who struggles with attention issues. “I don't know if it’s ADHD or if it’s lead,” he says, “so I just work with it.” A decade later, he’s still furious about what happened. “You can’t help but to be enraged,” he says.

In January, Simmons testified virtually at an EPA hearing to gather comments for a plan to strengthen the Lead and Copper Rule, the 1991 law regulating lead levels in drinking water. The EPA had proposed lowering the remedial action level from 15 to 10 parts per billion (a part per billion is roughly the equivalent of one drop in 500 barrels of water). Simmons spoke in favor of the change. “We are the United States of America,” he said, in a tone of disbelief. “Children, right now, are having developmental issues that started from the day they were born.”

"I was a whole lot sharper prior to the water crisis,” says Marcell Simmons, a clean water activist in Flint, Michigan. A decade later, he’s still furious about what happened. “You can’t help but to be enraged.”

Photography by Kimberly Todd

Dionna Brown also spoke at the hearing. “No amount of lead in drinking water is deemed safe,” she said. Brown came from a middle-class family and didn’t use the services being offered in Flint. “I have to work harder to get what I want,” she says. “It's not okay that I have to work harder, but there’s nothing I can’t do if I put my mind to it.”

While in college, Brown became involved with the nonprofit Young, Gifted & Green, where she now works to eliminate lead in communities like Flint. She says the water crisis helped open her eyes to historic environmental injustice. “This is the history of America,” she says. “We see where the power plants are located, where the trash incinerators are, where all these environmental hazards are placed—they’re placed in Black, brown, and low-income areas.”

Besides wide-scale lead exposure, the crisis also sparked a deadly outbreak of Legionnaires’ disease, which sickened dozens and took the lives of at least 12 people. Nine public officials, including emergency managers appointed by the state, were criminally charged for their roles in the disaster. None were convicted and, last year, all remaining charges were dismissed.

The crisis was an injustice on many fronts, says Debra Furr-Holden, dean of the New York University School of Global Public Health. Furr-Holden lived in Flint as a child and worked as a public health researcher at Michigan State during the crisis. Indeed, if Flint were not a poor, majority-Black city, she says, the water crisis might never have happened. “This tolerance for water that the government knew was not potable being allowed to flow out of people’s taps—we just don’t believe this would have ever happened in an East Lansing or Lansing or Grand Rapids,” she says, calling the crisis an outright “act of environmental racism.”

The full health effects of the water crisis on the children of Flint won’t be known for another 10 to 15 years, Furr-Holden notes. “We already know what lead does in the body … what lead does to the brain,” she says. “Can we overcome that with intervention? Yes, but we won’t know how well we did until these kids reach adolescence and young adulthood.”

Furr-Holden credits the assessment clinic, the Pediatric Public Health Initiative, and the replacement of lead service lines as critical to the recovery. Another key is the state’s expansion of Medicaid for children in Flint who will need years of support, she says, to address the ongoing health effects and psychological trauma from the disaster.

The people of Flint carry on. Shaketta Brooks volunteers with the National Parents Union, devoted to the rights of minority and low-income parents. “It’s part of the healing for me,” she says.

Marcell Simmons attends community college and plans to pursue a career in communications. He says he’s eager to kayak the river once the weather warms. Dionna Brown says she plans to go to law school in 2026. “I’m a child of the Flint water crisis,” she says. “I’m the example that Flint kids are successful and can be successful, even though so many people doubted us.”

The Gilleylen family welcomed another child in 2017. They say their daughter’s behavior has improved some, and she thrives as a young athlete. They’re now planning to buy their first home, outside the city limits.