Cincinnati schools are using an app to identify suicidal kids. Not everyone is convinced

The story was originally published by Cincinnati Enquirer with support from our 2024 National Fellowship.

AI that's meant to identify kids at risk of hurting themselves or others has been tested in Cincinnati schools since 2016.

“Do you have hope, and how does that feel?”

I’m sitting at my kitchen counter, talking to a bespectacled blue owl named Claire. She stares at me unblinkingly from the computer screen.

“Yes,” I reply, somewhat uncertainly. I ramble on for a few more seconds – something about how hope comes from family, and friends, and what that feels like – before pausing. Have I spoken for long enough?

Claire appears satisfied with my response. “Thank you,” she says stiffly. “Now we will move on to secrets.”

After secrets, she asks whether I have anger (yes!), how it makes me feel (... angry?), whether I have fear (I do –), and lastly, emotional pain (who doesn’t?).

Finally, Claire informs me that the interview is over. Soon, I’ll receive the results of my $180 mental health risk assessment – as determined by artificial intelligence.

I’m not the only one to have my mental health assessed by AI.

Clairity – an AI app which can apparently detect mental health issues through voice recordings – is used by school-based clinicians at around 80 schools across Greater Cincinnati and, according to Clarigent Health, which developed the app, in universities, doctor’s offices, mental health centers, and juvenile justice programs in California and North Carolina, in addition to Ohio.

But nearly a decade after researchers first hailed the technology as a scientific breakthrough in mental health, it’s difficult to say whether Clairity ever met its intended goal of helping prevent youth suicide.

None of the Cincinnati schools that tested the technology, from 2016 onward, were able to attest to the AI’s effectiveness. And clinicians and school administrators contacted by The Enquirer could not provide data showing how well the app worked, independent of the research funded by Clairity’s developers.

While trained on a majority white population, the app is being used on kids of all races and backgrounds, which has some experts questioning its effectiveness.

Still, Clarigent is trying to expand it to more kids. A Spanish-language version of Clairity, and another algorithm that will analyze kids' language to determine their risk for committing violence, are currently in the works, according to Clarigent CEO Don Wright.

An offer schools couldn’t refuse

The arrival of the youth mental health crisis left schools desperate for solutions. In 2021, a rise in suicides made it the second-leading cause of death for kids between the ages of 10 and 14, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

After a student died by suicide at Three Rivers Local School District, former superintendent Craig Hockenberry said his community was devastated.

“If there’s anything that we can do to prevent it, it was a win-win,” Hockenberry said. “It didn’t matter what the program was.”

Enter Mason-based startup Clarigent Health with Clairity, a solution that seemed too good to be true.

According to the Clarigent, Clairity could empower clinicians to pick up on the subtlest signs of suicide risk and help youth who were suffering. While anyone can now buy a Clairity assessment from its website for $180, schools who enrolled in Clarigent’s study could access it for free.

Clarigent Health’s technology was first developed by Cincinnati Children’s, where a researcher named John Pestian spent over a decade analyzing the language of suicide.

Cincinnati Children's denied several requests for an interview with Pestian and directed all questions about Clairity to Clarigent.

John Pestian, a researcher and a professor of pediatrics, developed the algorithm that became Clairity. Pictured in 2016 for a previous story, Pestian declined The Enquirer's interview requests.

The Enquirer/ Liz Dufour

After analyzing more than 1,300 suicide notes and collecting interviews of suicidal teenagers treated in Cincinnati Children’s emergency department, Pestian developed an algorithm to find patterns in the ways that people express suicidality through speech. The machine learning algorithm would use this data to then make predictions about whether someone was contemplating suicide.

The impressive computing power of artificial intelligence, according to Pestian, could identify patterns in someone's voice data on a scale that humans never could.

"These are things you just don't pick up in conversation," he told The Enquirer in 2016.

According to his research, the algorithm could identify not only words, but also nonverbal cues such as pauses and tone, that indicated suicidality.

“No matter how smart we are, no matter how good we are, no matter how well-trained we are, the amount of information required for any given decision is moving beyond unassisted human capacity,” Dr. Tracy Glauser, child neurologist and associate director of the Cincinnati Children's Research Foundation, said at a 2023 panel hosted by the hospital. “That’s been our driving force."

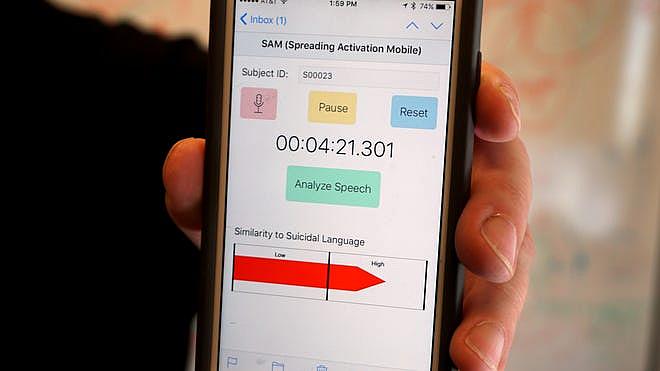

The result of Pestian’s research was Clairity’s predecessor, an app first known as Spreading Activation Mobile, or SAM, then as MHSAFE. The idea was that guidance counselors could download the app on their phones and use it to quickly identify kids who were at high risk of attempting suicide.

John Pestian and his team developed SAM, an app that aimed to detect suicidal language among teens. SAM later became Clairity.

Provided By Cincinnati Children's

All schools needed to gain access to the technology was to enroll kids in the study, with parent and student consent. The first was run by Cincinnati Children’s in the 2016-17 school year, and the second, by Clarigent Health in 2019-2020.

Where suicide prevention felt precarious and unpredictable, these apps offered certainty, science and hard numbers. Their legitimacy was bolstered by experts at Cincinnati Children’s. Moreover, this cutting-edge technology, supported by almost a million dollars in research funding from the National Institutes of Health, would be provided to schools at zero cost.

“We all kind of dropped our pencils,” said Hockenberry.

“If they could do it with a potential suicide, they could potentially catch a school shooter,” he remembered thinking.

Schools have 'no data' to provide on AI’s effectiveness

The Enquirer requested records from nearly 50 school districts in southwest Ohio and 15 in Northern Kentucky. Documents showed that Deer Park High School and four Cincinnati Public Schools – the School for Creative and Performing Arts and Dater High, Walnut Hills High and Aiken High schools – tested the 2016 version of the app. In the 2019-20 school year, Three Rivers Local School District and Lebanon City Schools also used Clairity.

But none of the districts had data to share on the AI’s efficacy. Most said that it was private, accessible only to the clinician and the family of the child.

The School for Creative and Performing Arts was one of the schools that tested an early version of Clairity, an AI-powered app designed to detect mental illness through voice data.

Elizabeth B. Kim/The Enquirer

Todd Yohey, former superintendent of Oak Hills Local School District and Lebanon City Schools, said he was “reasonably optimistic” about the algorithm. But he wasn’t sure how many kids were actually exposed to the app, and the school had no data about its usage.

“We had hundreds of students that were seen by the clinicians,” said Yohey, who worked with Cincinnati Children's to embed their clinicians within his schools. “I don’t know if they used the app.”

Hockenberry, now a superintendent in a Youngstown suburb, left Three Rivers before Clairity was launched. "I don't know of any of the outcomes," he said.

Ben Crotte, a former school-based counselor at SCPA, remembered testing an early version of Clairity in 2016.

Frank Bowen IV/The Enquirer

Ben Crotte, a former school-based therapist at the School for Creative and Performing Arts, estimates he recorded conversations with between 15 to 20 students – with their consent and their parents’ – as a part of his participation in the SAM research.

While he didn't receive the app's recommendations in real time, Pestian later told him that the AI identified two of his students as high risk for suicide, which Crotte already knew.

“The app seemed to nail them and identify them very well," Crotte said.

Still, Crotte said he didn't recommend hospitalization for either student. Had he received the app's results during his sessions, he wonders whether he may have felt “more pressured” to recommend hospitalization, which he described as “clinically unnecessary at that time.”

Ben Crotte with therapy dogs Tiki and Violet at Animal Companion Counseling, the mental health nonprofit he now runs in the West End.

Frank Bowen IV/The Enquirer

Best Point, a nonprofit provider of children’s mental health services, participated in Cincinnati Children’s early research in 2016, and now its clinicians use Clairity as a standard screening tool for kids ages 12 and up in around 80 schools across Cincinnati.

“We felt confident that it had been trialed and tested,” Debbie Gingrich, chief program officer of the organization, said.

Learning to use Clairity has been “a learning curve” for Best Point’s clinicians, Gingrich said, but Clairity has helped them identify “kids at risk that they would not have otherwise expected.”

Gingrich did not reply to multiple emails requesting data on the number of kids whose suicide risk would have gone undetected without Clairity's help.

Court tries Clairity, discontinues contract after 2 years

Hamilton County was the first in the country to use Clairity in its juvenile court. Headlines announced the partnership, which signaled AI’s potential to help solve an intensifying youth mental health crisis, with fanfare and excitement.

“We are proud to be the first court in the country to use these cutting-edge tools to better understand and serve our children,” said Hamilton County Prosecutor Melissa Powers, then a senior judge of Hamilton County Juvenile Court, in 2021. The court signed a $20,000 contract with Clarigent for the 2021-22 fiscal year and hoped the algorithm would help the court with referrals for mental health services and treatment interventions.

Staff from the Hamilton County Juvenile Court Assessment Center used Clairity on over 200 kids in juvenile court.

Frank Bowen IV/The Enquirer

Some kids in juvenile court aren’t as forthcoming about how they're feeling, said Deanna Nadermann, the court's director of behavioral health services and special projects. She saw how Clairity could help reach those kids and speed up the referral process for children behind bars.

For those kids, and others suffering from mental health issues, Nadermann said it's a long process to “cut through the red tape” of getting them admitted to inpatient care.

Megan Taylor, a licensed social worker and manager of the court’s assessment center, which helps connect kids to counseling, therapy, and case management services, shared Deanna’s excitement.

“I think we all thought this was going to be this great thing,” Taylor said.

Megan Taylor, manager of the Hamilton County Juvenile Court Assessment Center, was excited to use Clairity to help more kids get mental health care.

Frank Bowen IV/The Enquirer

Taylor, who oversaw the team of six staffers who would be using Clairity with their clients, remembers Clarigent Health’s training for the app to be simple and intuitive. But in practice, it was anything but. There were technical glitches and issues with staying connected to WiFi. They bought Kindles and microphones to help with the recordings, Nadermann said, but her staff still ran into problems. Clairity peppered users with errors, saying it couldn’t pick up the speaker, that the speaker wasn’t talking long enough or was speaking for too long.

“Half the time it wouldn't work,” Taylor said. “The app would just spin and just buffer and buffer.” And the way Clairity phrased questions were confusing to some of the kids. “Do you have emotional pain?” Taylor remembers one of the questions asked. “They were like, ‘what?’”

Staffers at Hamilton County Juvenile Court used fuzzy mics to record the data Clairity needed to assess suicide risk in their clients, but it didn't always work.

Taylor doesn't blame Clarigent Health for the difficulties her staff faced, which she mostly chalks up to the court's unreliable WiFi networks. The challenges of working with kids in juvenile court are unique, she added, so Clairity might work better in a hospital setting with staff who are clinically trained.

Clarigent said it tried to work with court staffers on the IT issues and safety protocols preventing youth from being positioned close to the device "presented unique challenges."

Data provided by Clarigent Health shows Clairity assessed the mental health of 222 youth in juvenile court. One-third were labeled as having medium to high risk for suicide. But it’s difficult to determine whether Clairity’s evaluations were consistent with staffers’ evaluations, or if those youth would have received mental health help anyway, because the court did not collect data on the app’s outcomes.

Nadermann said she was disappointed that Clarigent Health’s recommendation for medium and high-risk kids was to then administer a suicidality questionnaire. “Why don't I just do that assessment at the beginning?”

The court discontinued its contract with Clarigent after its second year.

Can AI predict suicide? Experts weigh in, discuss racial bias

People tend to be open with their clinicians about their suicidal ideation, said Jordan DeVylder, associate professor of social work at New York University. But clinicians “have a lot of trouble predicting” those who will act on those thoughts.

“That's where the appeal of these kind of machine learning approaches comes in," DeVylder said.

Computers are good at detecting subtle differences in people's voices, and DeVylder is confident in AI’s ability to detect suicidal language. But he’s worried about the ethical implications of using AI that’s too good at its job.

“Is it ethical to mandate treatment for someone who didn’t even actually talk about suicide based on an algorithm alone?” he asked.

WiFi issues often prevented Hamilton County Juvenile Court staff from using Clairity in this detention center.

Frank Bowen IV/The Enquirer

Another potential limitation to consider is the bias of the training data.

There's not a lot of research on how nonwhite people express mental illness through language, and most machine learning algorithms are trained on white people, said Sunny Rai, a postdoctoral researcher in the University of Pennsylvania’s department of computer and information science.

That's true of Clairity, too. According to an Enquirer review of research provided by Clarigent Health, three of the four studies on Clairity that published racial demographics had study populations that were 74% white or higher.

Rai's research used machine learning to show that Black people and white people express their depression differently on social media. While the white participants with depression in Rai's study tended to use more “I” pronouns that indicated excessive self-focus, the same was not true for Black participants.

Still, Clarigent CEO Don Wright maintained that Clairity's algorithm "is not biased." (He did not provide data or results of the 2021 NIH-funded study that he said proved that to be the case). Later, in a statement, the company said it "takes active steps to mitigate bias" by regularly testing its AI for "fairness and unintended biases", among other things.

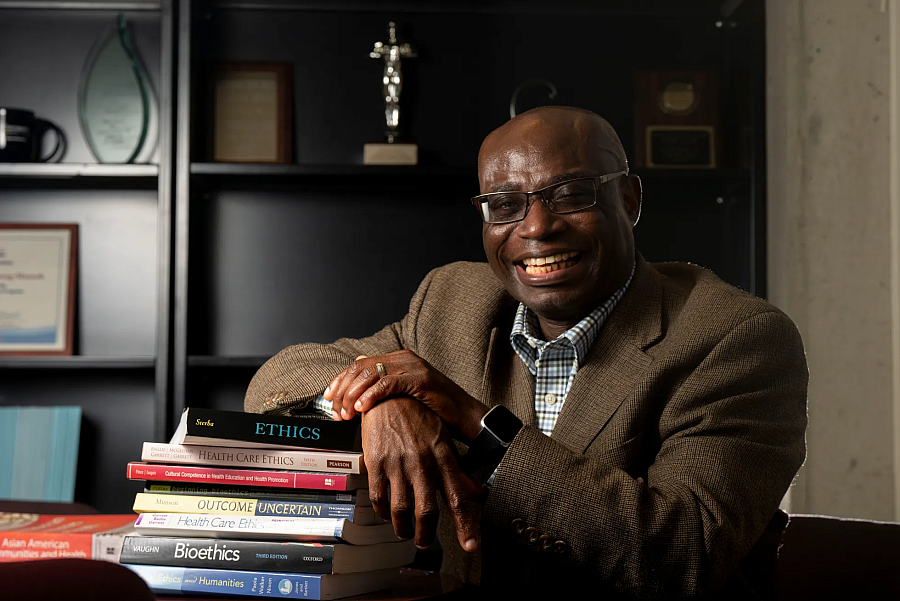

If the data the algorithm is trained on is not representative of the population it will be used on, the use of AI to detect suicide risk is both scientifically and ethically dubious, said Augustine Frimpong-Mansoh, professor of health care ethics at Northern Kentucky University.

Professor Augustine Frimpong-Mansoh, acting chair of the Department of Sociology, Anthropology and Philosophy at Northern Kentucky University, says Clairity's use poses both scientific and ethical concerns.

Albert Cesare/The Enquirer

There are also questions about informed consent. Parents desperate to get their child mental health treatment may have agreed to Clairity being used without understanding the risks, he said.

“They are likely to go along with whatever you have told them and sign on to it," he said.

It’s also impossible to know whether Clairity is actually helping schools prevent suicide because there's no way to know whether a student who was flagged would have taken their own life, said Chad Marlow, senior policy counsel for the American Civil Liberties Union.

Companies like Clarigent, Marlow said, are “taking advantage of schools and their fears and their incredibly strong desire to keep kids safe.”

“It’s based more on hope and adoption of marketing slogans than actual tested data," he said.

What AI said about my mental health

I’m a 25-year-old woman whose first language is Korean. Most people Clarigent Health trained its models on do not look or speak like me. And yet, I couldn’t shake my curiosity about the app’s abilities.

Would the AI be able to pick up signs of mental illness that I myself wasn’t aware of? Maybe 11 minutes of hearing me ramble would be enough.

Following my interview with Claire, the next step of my screener was connecting with a therapist who’d reveal my results through phone or video call. “No appointment and no waiting,” promised the email from Clarigent.

But the video call link buffered for 15 minutes, and the therapist who answered the phone was confused about why I called (I think there’s an AI that’s supposed to tell me whether I’m depressed?). She put me on hold.

When she returned, she apologized, explaining that Clairity is a new service. The AI detected anxiety, she says, but no depression or suicidality.

When I later asked Clarigent for documentation of my results, the company told me Clairity detected no signs of mental illness – anxiety or otherwise.

How great would it be if that were true?

If you or someone you know is thinking about suicide, help is available 24/7. Call or text 988 or chat at 988lifeline.org.