Crossroads of a plague

This story was reported by Spencer Kent, a grantee of the Dennis Hunt Fund for Health Journalism a program of the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2020 National Fellowship. He explore the ways racial disparities dating back more than 50 years left people of color in Newark vulnerable to a deadly virus.

Newark has suffered the most COVID-19 deaths and cases in New Jersey.

Photo by Andre Malok | NJ Advance Media

Chapter 1: A Plague Arrives in Newark

The haunting stare was frozen on his daughter’s face.

Walter Andrews found her in the middle of the night, dazed and unseeing as she rocked back and forth on his living room floor.

“Tasha! Tasha!” he said in a loud whisper. But she merely groaned, continuing to gaze ahead vacantly.

The plague arrived in Walter’s Newark household in early April. His father-in-law contracted COVID-19 first. Then his wife, Gloria. And now, he watched helplessly as his 33-year-old daughter, Latasha, suffered a coronavirus-related stroke.

Walter cared for his wife and daughter as they huddled together in bed. He brought Gloria, 64, and Tasha soup and tea, trying to nurse them back to health.

But both would be dead within days of each other. His father-in-law died about a week before Gloria. Then Tasha succumbed. And then the coronavirus took Walter’s brother.

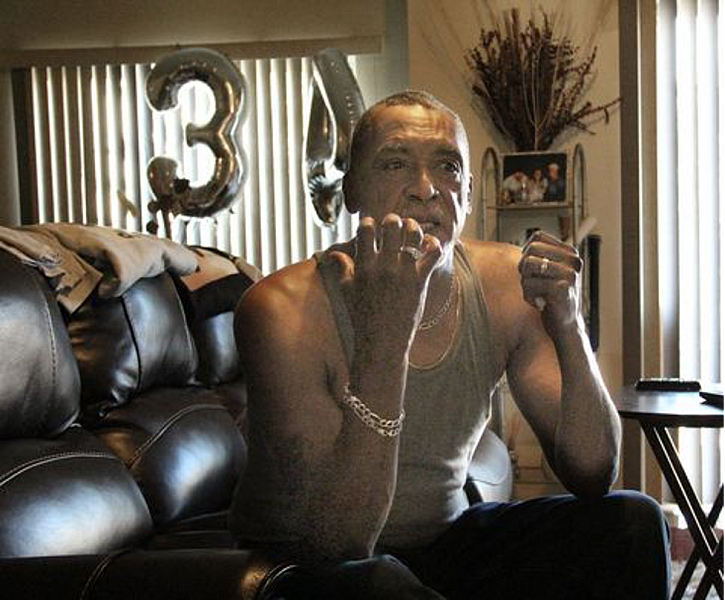

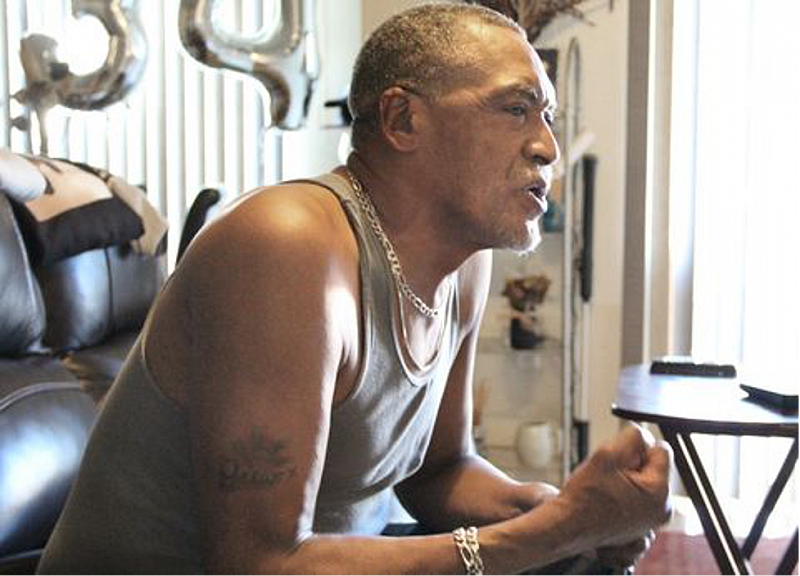

“How could it be?” Walter, 65, asked himself in a strained, raspy voice. He rarely cried. Now he couldn’t stop. The church custodian raised his arms and clenched both fists together in anguish, as if trying to strangle his pain.

“I outlived her,” Walter said in his empty house on Bragaw Avenue. “I brought (Tasha) into the world. That ain’t the way it’s supposed to be.”

The coronavirus emerged out of nowhere late last year, overwhelming Wuhan, China, before sweeping across the globe. When the novel virus reached Walter’s doorstep, it was just as terrifying as the international news coverage had warned.

COVID-19 devastated his family and then all of Newark, carving a lethal path through the gritty, 24-square-mile city with ruthless efficiency. Newark has suffered 727 coronavirus deaths and more than 18,500 cases, the most in all of hard-hit New Jersey.

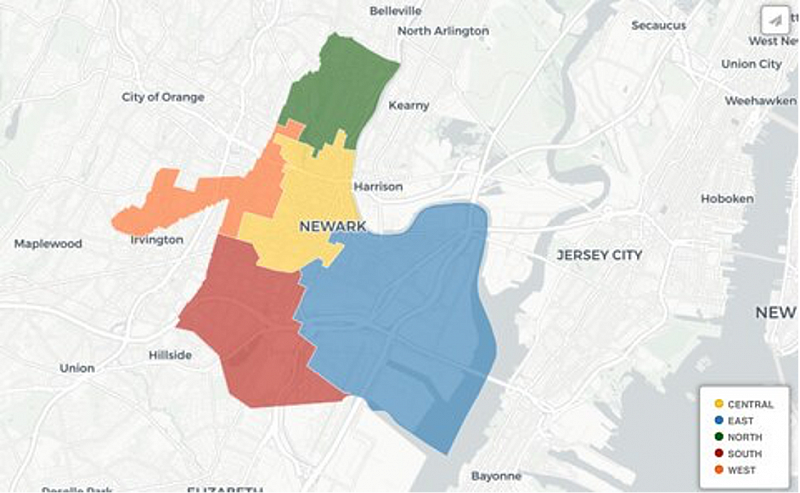

The virus cut an especially destructive swath of sickness and death from the western boundary of the South Ward to the eastern edge of the Central Ward, spanning three miles across the ZIP codes 07108, 07103 and 07102. It was the hottest of hot zones, the crossroads of the pandemic in the Brick City and home to a majority Black community.

Walter Andrews at home on Bragaw Avenue, trying to make sense of the loss of his wife, daughter, brother and father-in-law. Spencer Kent | NJ Advance Media

COVID-19 swept through University Hospital. Through Newark’s churches, claiming 15 congregants alone at St. Luke AME Church. Through the city’s nursing homes, taking the lives of 39 residents at New Vista Nursing and Rehabilitation Center. And through Newark’s legion of essential workers — people like Tasha Andrews, a civilian security guard with the New Jersey State Police.

The virus shattered multigenerational households like the Andrews family. It sickened Laura Bonas-Palmer and nearly killed her husband, Ray Palmer. And it left Al Jenkins with permanent scars and killed his 72-year-old mother, Dorothy Miller, who was taken away in an ambulance and never came home.

“The worst thing was those freezer trucks with the bodies. … That ripped some souls out of people,” Tamika Darden-Thomas, a Newark community activist, told NJ Advance Media, referring to the refrigerated trucks parked outside hospitals. In April, her 85-year-old grandmother and 66-year-old uncle succumbed to the virus.

The coronavirus preys on the elderly, the medically fragile and people of color, according to a September report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. And Newark, a city of 282,000, is nearly 50% Black, illustrating the stark divides the worst pandemic in a century has drawn along racial and class lines.

Put another way, the virus has exploited decades of systemic racism, leaving Black residents especially vulnerable. They are dying at disproportionate rates: There have been 30.49 Black deaths per 10,000 Newark residents versus 17.29 white deaths, as of Dec. 3.

“I knew it was going to be an onslaught. And indeed it was,” said Diane Taylor, a registered nurse at University Hospital, who has worked in Newark for more than three decades.

The city was awash in bodies in the spring as COVID-19 began its grim march through the five wards.

Newark's five wards each suffered their share of COVID-19 deaths and cases. Courtesy of the City of Newark

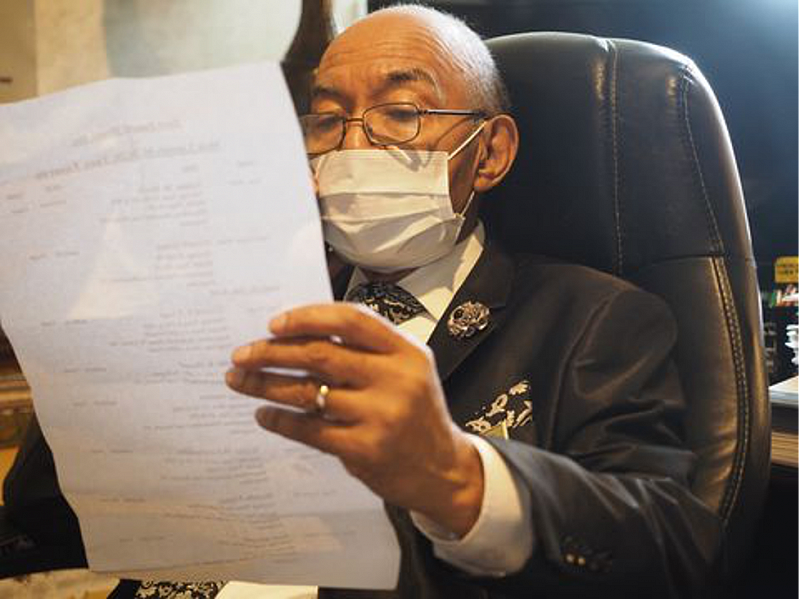

“It’s the first time in my 49 years of being here that I felt like I may lose control,” said Samuel C. Arnold, the president and manager of Perry Funeral Home.

Just as officials finally wrestled the initial surge under control, the pandemic’s second wave hit in October. And Newark was “ground zero,” Gov. Phil Murphy said.

By Nov. 9, there were 230 new cases a day, rivaling the number of positive tests at the peak of the first wave. By Thanksgiving, Mayor Ras Baraka again asked residents to stay home, locking down the city for 10 days as the virus spread out of control.

Lives continue to be at risk. The city’s economy is at stake. And Newark’s fragile rebirth — decades in the making — is threatened.

The Brick City slowly clawed its way back from the brink after the 1967 riots. Then AIDS. Crack. Corruption. And the years it was called “The Most Dangerous City in America.”

But the unimaginable public health crisis has jeopardized that progress.

Samuel Arnold, director of Perry's Funeral Home in Newark, feared he "may lose control" as the number of COVID-19 victims grew. Patti Sapone | NJ Advance Media

Despite the devastation, Murphy and Lt. Gov. Sheila Oliver have praised Newark’s response, and some have even hailed it as a shining example.

Baraka, the son of an activist poet, continues to take bold and proactive measures to protect the city, according to Junius Williams, Newark’s official historian and an attorney and civil rights activist since the 1960s.

Frontline medical workers like Taylor continue to fight for each desperately ill patient at University. Faith leaders like the Rev. Joseph Hooper shepherd their congregations through the horror. And activists like Darden-Thomas — the daughter of a homicide victim — advocate for the vulnerable and forgotten.

“I do believe that there is a spirit in Newark of resiliency,” said Larry Hamm, founder of the People’s Organization for Progress, a city-based social justice association.

Brick City remains an unflinching place filled with survivors.

This is their story.

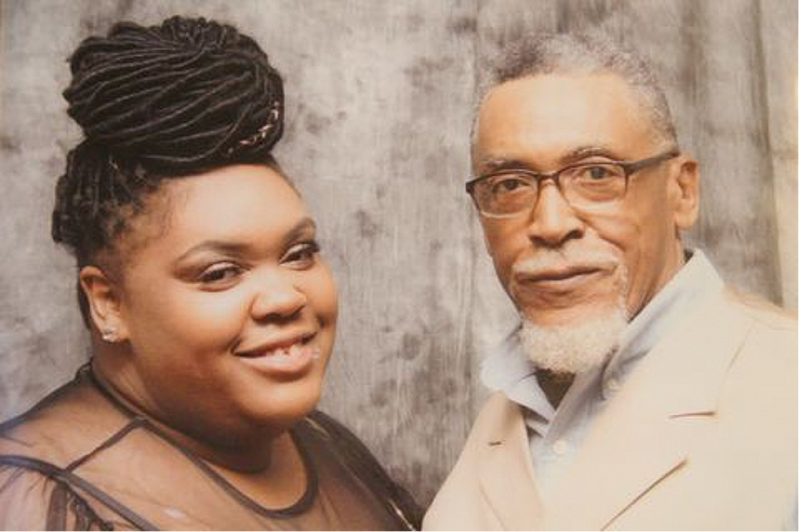

Latasha Andrews, 33, of Newark, with her father, Walter. Tasha, a civilian security guard with the New Jersey State Police, died of COVID-19 in April. Her mother, grandfather and uncle also succumbed to the virus. Photo courtesy of Walter Andrews

Chapter 2: Death and Desperation

The pandemic arrived in Newark on March 14.

A resident who worked in New York City became its first case.

By March 15, there were nine cases. By March 17, Newark mourned its first death.

COVID-19 was already raging undetected through the crossroads. It was quietly becoming a national epicenter even as media attention focused on early hot spots such as New York City, Bergen County and New Jersey’s horse racing community.

Throughout the neighborhoods of the Central and South wards — an uneven juxtaposition of new developments and gleaming businesses bordering crumbling

houses and drug corners — streets were suddenly deserted. From Jones Street and Springfield Avenue, where you can see the Prudential Center and downtown’s other jewels, to the Roberto Clemente Shalom Towers of Lincoln Park, those who could stay inside did.

Even bustling intersections like Broad and Market stood empty.

“It was like a ghost town,” Larry Hamm said.

The virus seizes on the very bonds that unite people. It has devastated nursing home residents and their caregivers. It has infected pastors and their parishioners. And it has torn through families all over Newark.

“So many families (were) getting infected — double funerals, husband and wives, mother, son,” said Kenneth Cattenhead, executive director of Family Funeral Home. “I did four family members in two weeks from one family.”

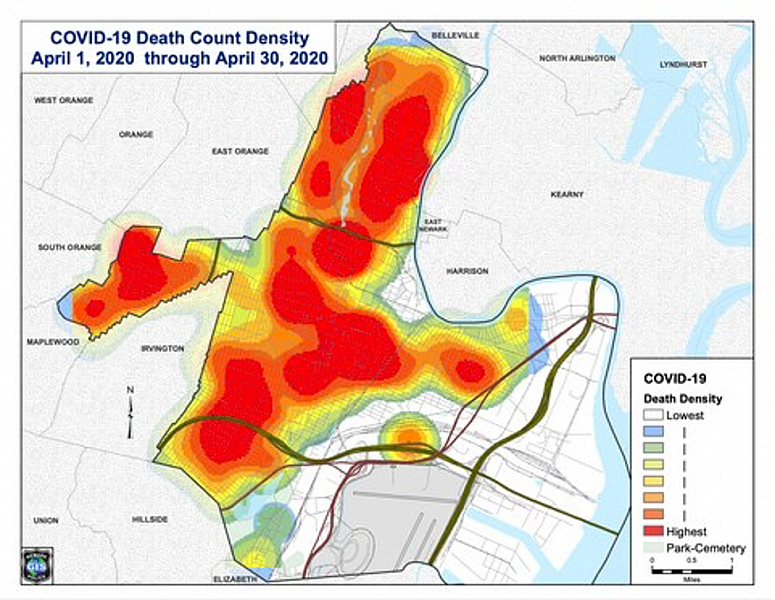

Heat maps tracing the volume of cases and deaths burned in a collage of angry reds and oranges for months, signifying Newark’s growing clusters.

A heat map compiled by the city showing the density of COVID-19 deaths in Newark in April.

The chilling peak of the first wave came in April, when Newark averaged 300 new cases a day. Daily death tolls approached 40.

Soon the bodies were everywhere.

“I just had to come up with ways to keep remains,” said Edith Churchman of James E. Churchman Jr. Funeral Home. “We were looking for funeral homes that could help us with storage of remains. The worst of it could never be told.”

“None of us have ever seen anything like this before,” she added.

The virus hit all races, all ethnicities, to varying degrees. The city’s Hispanic community has also suffered, with a death rate of 20.97 per 10,000 Newark residents.

Churchman and Samuel C. Arnold, the Perry Funeral Home manager, cared for those of every race during the pandemic — a rare development in Essex County, the most segregated in New Jersey, according to the 2020 County Health Rankings.

“It just washed away for a while,” said Arnold, whose funeral home predominantly serves Black families and sits between University Hospital and St. Luke AME Church in the Central Ward.

But skin color certainty mattered when it came to who the virus preyed upon most.

When the governor issued a stay-at-home order days after New Jersey’s first case was discovered on March 4, it exposed a sharp divide across the state.

Segregationist policies left the Black community disproportionately concentrated in overcrowded and neglected city neighborhoods. Poor schools and limited job opportunities widened education and wealth gaps. Unequal access to medical care and food deserts have perpetuated chronic health issues such as asthma, diabetes, obesity and heart disease, the CDC says.

The prevalence of those conditions is intrinsically linked to historic inequities that have made being poor and Black the most dangerous comorbidity of all.

And Newark, unlike the suburbs, is filled with essential workers who were unable to do their jobs from home.

It left mechanics like Al Jenkins and custodians like Walter Andrews venturing to their jobs instead of sheltering in place.

“Essential workers got to go to work,” Mayor Ras Baraka said. “You’re talking about a huge population of our city.”

Newark Penn Station, one of many transit hubs in the city that helped spread the coronavirus. Patti Sapone | NJ Advance Media

Brick City’s standing as a critical transportation hub — encompassing Newark Liberty International Airport, Penn Station, the PATH system, and NJ Transit buses and trains — only aided the virus’ spread. Many essential workers use mass transit systems daily, exposed to a higher risk of contracting COVID-19.

But no one was off-limits from the reaches of the coronavirus. Even Baraka’s mother was infected.

In the Fairmont neighborhood, Ray Palmer was coughing up blood in early April. The property manager gasped for air as his temperature soared. Delirium filled him with wild visions and hallucinations of flashing light.

His wife, Laura Bonas-Palmer, monitored her own COVID-19-related fever and cough as she cared for him at their South 8th Street home.

“My chest felt like it was just on fire,” she said.

But she worried about her Ray, 54, fearing the man with the shaved head and beaming smile would not survive.

“I was really worried — literally worried — that my husband was going to die at home,” said Laura, 51, who runs an art gallery in the city.

Taking the thermometer out of Ray’s mouth, Laura saw a reading of 104.6 degrees. She panicked.

“I didn’t know what to do,” she said, anxiety building in her voice.

About three miles away, Hameenah Muhammad feared for her own husband.

She had a coronavirus-related fever, but Jenkins was faring much worse. The mechanic has asthma, diabetes and heart disease — a trifecta of underlying conditions that greatly increased his risk of grave complications with COVID-19.

Like the Andrews and Palmer families, they did not know how the virus invaded their home.

Al’s mother had already been taken away in an ambulance after contracting the coronavirus.

“She never came back,” said Hameenah, a paraprofessional in Newark.

Then Al’s temperature reached 104 degrees and his other symptoms worsened.

“He couldn’t breathe,” Hameenah said.

They needed help. Fast.

Al Jenkins was on a ventilator for three weeks due to COVID-19. He lost his mother to the virus. Photo courtesy of Hameenah Muhammad

Chapter 3: Death Came to the House of the Lord

The call left the Rev. Joseph Hooper reeling.

The pastor had just finished a virtual Bible study when he was informed that LeRoy Smith, St. Luke AME Church’s 53-year-old musician, had died April 1 from COVID-19.

Hooper stood frozen for a moment, then collapsed on his sofa and cried.

“That one was very shocking,” he said in a low, solemn voice.

The virus had infiltrated the Lord’s house — Hooper’s house — a close-knit congregation of 675 members.

But that loss was only the first.

More calls would follow. One death became two. Two became three. Over the next several weeks, 15 of his parishioners would perish.

Hooper was shattered. He had no pulpit to stand behind, no congregation to console as the city and state were locked down. The virus had separated him from his flock when it needed him most.

“This was the first time that I had members dying that I wasn’t at their bedside, with the family when it happened … because we were not allowed to go into the hospital,” said Hooper, a bespectacled man who usually preaches in a bow-tie.

St. Luke, a small, brick building on Clinton Avenue with sloped, stained-glass windows and an iron gate surrounding the property, stands on the edge of the Springfield/Belmont and South Broad Street neighborhoods. Dionne Warwick launched her career here just after World War II, making her debut in front of a large audience at the age of 6. Her grandfather, the Rev. Elzae Warrick, was pastor and asked her to sing for his congregation.

But the church has been emptier than usual since the spring.

“You can imagine the toll it took on the church, to the point where they are afraid to even think about coming back into the building because of all those we have lost,” Hooper said.

The intersection of Martin Luther King Boulevard and Market Street in Newark. Andre Malok | NJ Advance Media

Months after the rash of deaths, many congregants are still unable to talk about it. The devastation remains too fresh.

“We’re a congregation that’s on the mend in terms of trying to make sense of this whole situation that took place,” said Hooper, 57. “And they are still struggling with this.

“This will be with us, I believe, for a long period of time.”

St. Luke was hardly the only congregation in the crossroads devastated by the coronavirus.

COVID-19 claimed the lives of the Rev. Samuel Austin, pastor of the First Corinthian Missionary Baptist Church on 18th Avenue, and his wife, First Lady Rev. Dorothy Austin.

Samuel, 64, and Dorothy, 70, had contracted the virus in late March. They died five days apart in April at Newark Beth Israel Medical Center.

“It was devastating,” said Barbara Moultrie, 61, a congregant and Caldwell resident. “The church members are still grieving. Not only were they my pastors … but they were my friends.”

The losses extended beyond death.

Walter Andrews worked as a custodian at Mount Pleasant Missionary Baptist Church on Montgomery Street, where Gloria and Tasha were parishioners. But churches were not immune to the economic reality of the pandemic. First the virus took four members of his family. Then it took his job this spring.

Walter was laid off by the church.

Diane Taylor, a registered nurse at University Hospital, has worked in Newark for more than three decades. Patti Sapone | NJ Advance Media

Chapter 4: The Front Lines

The older woman’s eyes were wide open, almost pleading with the doctors and nurses to help her.

She had the look — the expression of naked fear that has become all too familiar to health care workers in the pandemic. It sends shivers through even the most hardened among them.

The terrified woman was struggling to breathe when she arrived in University Hospital’s emergency department.

“She knew she was in trouble,” said Diane Taylor, a registered nurse who has kind eyes and wears a bandana-style scrub cap during her shifts.

Taylor had seen enough cases by that April day to recognize the woman was in crisis. By then, the Bergen Street hospital — one of only three left in the city — was overwhelmed by sickness and death.

At the peak in April, about 300 COVID-19 patients filled University, with another 10 to 20 new cases arriving daily, said Dr. Shereef Elnahal, its president and CEO and a former state health commissioner. The hospital stationed refrigerated trucks in its parking lot to house all the dead.

Emergency staff helps load a COVID-19 victim into one of the refrigerated trucks at University Hospital in April. Photo courtesy Edwin J. Torres/N.J. Governor’s Office

University faced such a deluge of patients that it threatened to overrun the hospital. Staff had to make an urgent plea for help one April morning, and Newark’s emergency medical services team dropped off additional personnel on the roof via helicopter, as if it were a scene in an action movie.

Stretched to its limits, University ran low on personal protective equipment and staff. Nurses held the hands of dying patients and used their own phones to call family members so they could say their final goodbyes over FaceTime. Many would later exhibit symptoms similar to post-traumatic stress disorder.

“It was all hands on deck,” said Jonathan Green, executive director of the emergency department. “It was moving patients in and out of rooms, because as soon as you got one patient stabilized, the sicker patient came in and needed the room.”

University Hospital, a factory of diagonal-shaped buildings stacked on top of one another, is a 518-bed facility in the Central Ward. The only public hospital in New Jersey is tasked with a critical mission: meeting Newark’s outsized public health needs. University is the largest supplier of care for uninsured patients in the state and a Level 1 trauma center that handles the worst of the worst emergencies. Shootings. Stabbings. Car crashes.

Almost 30% of Newark residents live in poverty, according to U.S. census data. The ZIP codes in the crossroads — 07108, 07103 and 07102 — are among the poorest in the state.

When the crisis hit, many patients from those neighborhoods got sick — patients like the frightened older woman.

She needed to be intubated to help her breathe. Taylor and other medical workers stood by her bedside, explaining the process to her. In the early days of the pandemic, 60% to 88% of COVID-19 patients on ventilators died, according to medical studies.

University Hospital's busy intensive care unit in April, during the peak of the first wave. Photo courtesy Edwin J. Torres/NJ Governor’s Office

Gasping for air, the woman had one request.

“Please let my husband know,” she begged. “We’ve been together for 50 years.”

Something in the woman’s voice shook Taylor.

“Here she was — she knew she was going to be intubated … probably knew that she was at risk for not making it,” she said. “And the husband not being at her bedside — all of that was just going through my mind, and it was really, really emotional.”

They reached the woman’s husband by phone, but she was already in an induced coma with a tube down her throat.

Within two or three days, she was dead.

“It was just the loneliness of dying alone. That really stressed me a lot…” Taylor said. “This to me felt like a yanking away of life.”

The summer brought a reprieve as cases and deaths fell. But University’s staff expressed wariness when the number of COVID-19 patients began to rise again in the fall.

“I definitely do see some of our staff are getting worried...” Green said in late October. “And there is that sense of dread.”

They were right to be afraid.

Just days later, New Jersey Health Commissioner Judith Persichilli declared Newark was again a “hot spot.” The city recorded 531 new cases over the weekend of Nov. 14-15.

Even as the promise of a vaccine grows closer to reality for the general public, the disease continues to ravage African Americans and other minority communities. In the 281 days since the virus arrived in New Jersey, the state has lost more than 17,500 lives and saw more than 381,000 infected.

And a long, dark winter awaits.

“People are lost. People are scared. People are confused,” activist Tamika Darden-Thomas said. “We don’t know which way to go.”

Laura Bonas-Palmer and her husband, Ray Palmer, at the art gallery in Newark that she runs. Patti Sapone | NJ Advance Media

Chapter 5: The Home Front

Laura Bonas-Palmer was on her own.

She brought Ray to St. Barnabas Medical Center when his fever spiked, but the Livingston hospital would not admit him, she said. Workers told her Ray’s oxygen level wasn’t low enough, she added.

Days later, they tried Newark Beth Israel, but were denied there too, Laura said. She then pleaded in tears with their primary care doctor, asking if there was any way he could help. He couldn’t.

“I don’t know what the hell I was gonna do,” Laura said, “but I was going to have to try my best to do something to save him, because obviously, the hospital wasn’t going to do it.”

Beth Israel and St. Barnabas, both members of the RWJBarnabas Health system, declined to comment on Ray’s case. However, spokeswomen for the hospitals said “a thorough review of a person’s medical history, risk factors, vital signs and results of diagnostic testing” are among the medical information used in evaluating whether suspected COVID-19 patients should be admitted.

Laura called her cousin, a nurse who works in New York City, for guidance. She could barely get the words out.

“I was frantic,” Laura said.

Her cousin said to cover Ray’s body with ice.

Laura rushed down the spiral staircase in their two-story, brick row house, emptied ice cubes from the freezer and put them in plastic bags. She then laid them on Ray’s head, chest and groin. She also covered him with cold, wet towels.

She then said a prayer and took his temperature again.

While many were dying in hospitals, others were fighting COVID-19 at home.

Some, like the Palmers, were turned away from medical facilities. Others chose to avoid hospitals they were suspicious of even before the pandemic, part of a long history of mistrust the Black community harbors since the infamous Tuskegee syphilis study and other medical experimentation on people of color.

Al Jenkins, and his wife, Hameenah Muhammad. In April, Al needed to be placed on a ventilator. He also lost his mother to the virus. Photo courtesy of Hameenah Muhammad

Between mid-March and the end of April, University Hospital’s EMS team reported a 200% spike in residents found dead on arrival, said Dr. Chris Pernell, chief strategic integration and health equity officer.

Not all succumbed to the virus. But Black residents were overrepresented among DOAs with COVID-19 symptoms and without, she added.

“You can imagine that during the height of the surge, when there was a great frenzy and a lot of fear, you layer that on top of any baseline mistrust around public health systems,” Pernell said.

From the beginning, University’s staff knew that a city filled with poverty and essential workers was vulnerable. Newark was a perfect incubator for spread.

Jonathan Green, who runs the hospital’s emergency department, ticked off the reasons: Population density. Multigenerational households. The proportion of residents who can’t stay home.

Al Jenkins, and his wife, Hameenah Muhammad, both survived bouts with COVID-19. Photo courtesy of Hameenah Muhammad

“Black and brown communities were hit much harder because people are much more likely to be working in jobs where they had to go in person and interact with people,” said Leslie Kantor, professor at the Rutgers School of Public Health.

“If you’re a working-class person, you’re just being put in the line of fire so much more,” she added.

Across the city, Al Jenkins was losing his battle with the coronavirus.

He was admitted to Newark Beth Israel on April 11.

Doctors discovered Al, 52, had pneumonia and two blood clots — one in his lung and one in his leg. He could no longer breathe on his own.

They put him on a ventilator and hoped he could beat the odds.

A day later, his mother died in St. Barnabas from COVID-19.

Tamika Darden-Thomas stands on Bergen Street in Newark. In April, Darden-Thomas' 85-year-old grandmother, Nora Darden-McNeil, and 66-year-old uncle, Vincent Eley, succumbed to the virus. Patti Sapone | NJ Advance Media

Chapter 6: Built Newark Tough

The body mysteriously washed up on the beach in 1981, abandoned more than 120 miles from home.

No one knows how Gregory Thomas ended up on the sand in Brigantine. No one seemed to care enough to find out.

Thomas was only 26. His daughter, Tamika Darden-Thomas, was just 5 when he died.

“I remember that like it was yesterday, just walking through Perry’s Funeral Home, up and down the stairs as the only child in there … trying to figure it out,” Tamika said. “And my mom said, ‘He’s just in a deep sleep.’”

The killing would become a turning point for a family that soon unraveled and for a young life that would endure far too much pain.

After her father’s death, Tamika said she was repeatedly molested by a family member, a secret she kept for years. She then was raped as an adult. Her partner left her right after she had her son, Ty-mik G. Koonce, she said. And she twice attempted suicide — the first time when she was only 14.

Trauma after trauma. Betrayal after betrayal. An all-too-familiar story in a city that has seen far too many tragedies.

But there was one woman who helped Tamika rise above the pain and anger. Her grandmother, Nora Darden-McNeil, helped raise her and inspired her to give back to her community.

Tamika channeled the hurt into activism as a form of therapy. It soon became a calling.

“I wanted to be able to speak up for the voiceless,” she said.

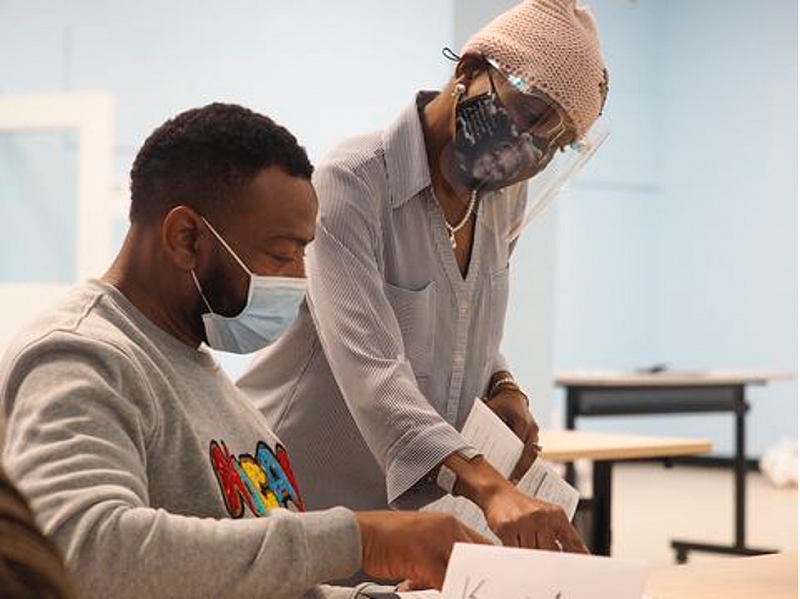

Tamika, 45, is an assistant data management coordinator at NewarkWorks One-Stop Career Center, helping city residents and ex-offenders find jobs. She also runs a nonprofit organization — the Gregory Thomas Foundation — to reach kids and young adults in the community and promote education.

Tamika was devastated twice in the past five years when young men she mentored were gunned down in street violence.

She might have faced a life on the streets herself if Nora and her generosity hadn’t rescued her.

“She fed everybody from the Weequahic section,” Tamika said of Sunday dinners that included macaroni and cheese, turkey kielbasa, sweet potato pie and turkey wings. “She fed homeless people. And I have that habit now.”

Nora also mentored and cooked for at-risk youth for more than 10 years at two juvenile detention centers: The Ogden Residential Group Home in Newark and the Liberty Park Hudson Day Program in Jersey City.

But tragedy wasn’t done with the family just yet.

Nora, 85, contracted COVID-19 this spring. Tamika’s uncle, Vincent Eley, 66, also came down with the virus in an Irvington nursing facility.

Nora’s symptoms started mildly enough. But soon she could not stand on her own. Then she could not speak.

Nora spent her final two weeks alone in Mountainside Medical Center in Montclair, unable to receive visitors. She died April 29.

Tamika was still mourning a month later when a new crisis threatened the city.

Looted stores along Broome Street during the 1967 Newark riots. Al Lowe

Chapter 7: Wounds of the Past

The city was burning all around them.

Gunshots rang out day and night. Bullet casings and shattered glass littered the streets.

For five days, Newark was bedlam. Fires and looting gutted Springfield Avenue. National Guard troops and police officers swarmed the streets, crouching behind their vehicles and firing on buildings. Demonstrators hurled bricks and rocks at them.

Tensions boiled over in July 1967 after police arrested and beat a 40-year-old Black cab driver and jazz trumpeter, John William Smith, following a routine traffic stop. By the end of the uprising, 26 lay dead and the city was in ruins.

Lt. Gov. Sheila Oliver was a teenager growing up in the South Ward 53 years ago. She recalled walking with friends near Lyons Avenue and Bergen Street as the National Guard rolled through the city.

“There were two tanks there,” Oliver recalled. “And there were soldiers in their camouflage uniforms and everything, and we couldn’t walk any further than there.”

Five decades later, city leaders worried it could happen all over again after the video of George Floyd’s death in Minneapolis ignited rage.

They knew that years of discrimination, police brutality and government corruption turned Newark into a powder keg in 1967. And its neighborhoods exploded in violence, a moment that has defined the city for decades.

New Jersey National Guardsmen holding men at gunpoint during the Newark riots in 1967. Picture collection/Newark Library

Newark couldn’t endure it again — especially during a pandemic.

“It hurt us more than it helped us,” Tamika Darden-Thomas said of the riots. “And we’re still trying to come back from the properties that were damaged and burnt down and destroyed by us. Because we were angry. We were angry at the system.”

White flight, which had begun before the uprising, surged in the aftermath. Newark was 83% white in 1950. By 1970, it was 44% and falling. Many businesses went with them in the exodus.

Federal housing policies subsidized mortgages in the suburbs, and infrastructure projects offered new opportunities for white families to move while commuting to their jobs in the city.

“They (the federal government) are the ones who codified redlining, with the maps with the red around a block,” said Richard Cammarieri, the director of special projects at the New Community Corporation, a community development organization founded after the riots.

“But those are the kind of things that led to the disinvestment, the deterioration of cities like Newark, and they’re all racially targeted,” he added.

That degradation helped spawn the social and financial ills that the pandemic would exploit five decades later.

Mayor Ras Baraka speaks at the People’s Organization For Progress emergency march for Breonna Taylor at the Lincoln Statue on Springfield Avenue in Newark. Michael Mancuso | NJ Advance Media

The late activist Amiri Baraka was among those protesting in the streets during the uprising. He too had been beaten by police. When the coronavirus crisis hit, it fell on his son to protect Newark.

An unexpected phone call Feb. 2 would alert Mayor Ras Baraka to how destructive the outbreak in China could be for his city.

Baraka had been at a friend’s house watching the Super Bowl when a call came from a staffer. Mayors from across the country were being summoned for a conference call with federal officials.

Members of the Department of Intergovernmental Affairs had used the word “pandemic.” They discussed how to handle flights coming in from China, where the virus originated, including to Newark airport.

“They said on the phone that ‘This is a pandemic — that eventually … it would find its way outside of China. And what we’re doing is trying to slow down that process,’” said Baraka, 50.

“I felt like we were on our own,” he added.

The federal government’s inadequate response to the pandemic included a failure to document the high rates of infection and death among Black and Hispanic Americans, CDC Director Robert Redfield admitted in June. Meanwhile, the state established drive-thru testing sites in the spring near highways and at colleges, rendering testing inaccessible for many city residents without cars.

So Newark moved quickly and often unilaterally in March and April. It closed its borders, erected testing sites in hot spots, initiated its own contact tracing and relocated the homeless and tested them.

There was no other choice, Baraka says.

“The people who live in this community are more likely to catch COVID-19 than anybody else and are more likely to die,” he said in November.

Baraka was aggressive in enforcing compliance. Police would issue summonses to those not wearing masks in public or to people driving for nonessential needs. When the state limited social gatherings to 10 people, the city cut it to five.

“Mayor Baraka’s response, I don’t think was overkill,” Oliver said. “I was proud of him quite frankly — he and his administration.

“As he began to see transmission rates, infection rates, and University Hospital in Newark and St. Michael’s Hospital in Newark — as he began to see that happening in his city, and he saw that people were not self-regulating themselves, he took it into his own hands to bring down the hammer.”

A woman walks past National Guard troops and State Police officers during the riots in Newark that took place from July 12-17, 1967. Star-Ledger archives

The turbulent administrations of Hugh Addonizio, Kenneth Gibson and Sharpe James eroded the city’s faith in its leaders. Violent crime spiked. Corruption ran wild. Addonizio, Gibson and James each were convicted or pleaded guilty to federal criminal charges, although not always for crimes committed during their time in office.

But Baraka has restored the public’s trust in city hall, community leaders say.

“The population now does not see Mayor Baraka as the enemy. They see him as a progressive force, as a person, as a man, who’s trying to make things better,” said Junius Williams, Newark’s official historian.

Of course, systemic problems still besiege the city. Violent crime has risen since the spring, including the Thanksgiving weekend shootings of a 12-year-old boy and a 14-year-old girl in separate incidents. Its schools have been closed since March, when Gov. Phil Murphy locked down the state, and they won’t reopen until late January at the earliest. The Newark water crisis forced thousands to use filters or drink bottled water for years to avoid lead contamination.

And two recent indictments show city hall still struggles with corruption. West Ward Councilman Joseph McCallum Jr. was charged with one count of wire fraud in an alleged kickback scheme involving developers. And Carmelo Garcia, who worked as deputy mayor and acting director of the Newark Department of Economic and Housing Development from 2017 to 2018, was accused of accepting jewelry and more than $25,000 in cash as bribes.

But by early May, Newark had reduced new coronavirus cases to less than 100 a day.

Despite the measures taken, city officials knew their residents were still vulnerable, whether due to poverty, homelessness or pre-existing conditions like diabetes, which Gloria and Tasha Andrews both had.

“The disparities that were already in place really just compounded the inadequate response,” Hamm said.

And then Floyd was killed, and new problems confronted the city.

Larry Hamm addresses the crowd at a rally and march by the People’s Organization for Progress to protest the killing of George Floyd. Michael Mancuso | NJ Advance Media

Chapter 8: The Street Warriors

A sea of protesters filled the plaza.

About 3,500 people assembled at the base of the Seated Lincoln statue near the Essex County courthouse to demonstrate against police brutality. And tensions were high.

They carried signs bearing slogans such as “Stop killing us” and “Keep your knee off our neck.” They wore T-shirts featuring the message, “I can’t breathe.” They chanted. They marched.

Larry Hamm, who’s led countless protests over the years and organized the May 30 rally, was shocked by the size of the crowd.

“I was somewhat nervous,” he said.

Newark leaders watched the unrest in Minneapolis spread west to Seattle and Portland and east to New York, which would see weeks of tumultuous protests.

They knew anger was building. They remembered what happened in 1967. So they mobilized.

Activists. Pastors. Community organizations. City leaders. And the divergent groups joined forces.

Hamm was planning the rally on May 29 when the mayor texted him, asking him to speak at a morning news conference.

Baraka had been organizing on his end, trying to figure out a way to keep the peace while giving residents a voice and a productive way to express their anger. His brother and chief of staff, Amiri Baraka Jr., was reaching out to activists and clergy to get them into the streets.

“We obviously were nervous because of what was happening around the country,” Baraka said. “People burning precincts, all kinds of craziness.”

Many residents have long distrusted the Newark police. Their suspicions were proven well-founded in 2014 when a U.S. Department of Justice investigation found sweeping misconduct and civil rights violations. The damning report eventually led to a consent decree allowing a federal monitor to oversee the police department.

That distrust concerned leaders as the uneasiness grew.

Wearing a purple, button-down shirt and an N-95 mask, Baraka acknowledged the painful moment at the media briefing. He exhorted the crowd “to fight the pandemic of coronavirus and ... the pandemic of racism and white supremacy.”

But he warned protesters to heed the hard lessons of a half-century earlier.

“In 1967, Newark went up in flames for four days,” said Baraka, an urgency in his voice as the microphone echoed. “Dozens of people died. The city was destroyed. And we still are trying to recover from that today.”

Demonstrators gathered in Newark on May 30 to protest the killing of George Floyd by a police officer in Minneapolis and to call for an end to police brutality. Michael Mancuso | NJ Advance Media

Hamm, 66, approached the podium next holding a large sign over his head that read: “Justice for George Floyd and all victims of police brutality.”

“It’s all right to be outraged,” Hamm said, nodding his head. “It’s all right to be angry about what happened. We must take our outrage, and take our anger, and take our righteous indignation, and turn it into energy to organize our people to fight against the forces of racism and oppression here in the United States.”

But he wanted them to do it with a march “we can be proud of,” he said.

And Hamm would be proud.

It was peaceful, just like other protests held that weekend. Newark was widely praised for its nonviolent demonstrations as other American cities erupted in chaos.

“The community folks in the city really carried it — public employees were out, the citizens, clergy,” Baraka said.

They came together, just as they had in March and April to help distribute meals to the lines of hungry people that wrapped around streets during the state lockdown.

“Newark was going to be the place where we really (were) going to try to achieve Black political power,” Hamm said. “And I think that spirit has come down through the generations.”

City leaders joined thousands of demonstrators at the 1st Precinct on 17th Avenue — formerly known as the 4th Precinct, where the bedlam started 53 years earlier. Police officers wearing riot gear formed a line in front of the building, preventing some members of the crowd from entering. But community members soon moved the protesters back.

Newark Police Division Commanders were also present at the rally and march to the 1st Precinct, according to Director of Public Safety Anthony Ambrose, who monitored the protests from police headquarters. Tires on at least one police vehicle were slashed near the precinct, but there were no arrests or serious injuries reported.

The Rev. Louise Scott-Roundtree, a mayoral aide for clergy affairs, was out in the streets, speaking to the often young demonstrators. The goal was to defuse tense situations before they turned destructive and prevent the outside agitators who had descended on the city from escalating the protests, she said.

“A lot of outsiders were here,” Scott-Roundtree said.

Bishop Cleveland Blash, a retired pastor formerly of St. Paul’s Sounds of Praise Church, knew what was at stake.

He was praying for peace in the city during the protests, despite having contracted COVID-19 earlier in May and spending several days in the hospital.

“I honestly believe that Newark has not burned or gone through the rioting and looting because one of the main factors is the clergy of the city is together,” Blash said.

Walter Andrews, 65, at his home in September, several months after the death of his wife, daughter, father-in-law and brother to COVID-19. Balloons commemorating his late daughter's 34th birthday float behind him. Spencer Kent | NJ Advance Media

Chapter 9: The Survivors

The house on Bragaw Avenue is quiet. Much too quiet.

Every day, Walter Andrews takes the early bus to work at a new church — the Greater Abyssinian Baptist Church in the South Ward — and arrives home around 5 p.m.

When he returns, he walks into a silent home with two empty bedrooms. He sleeps in a room across from the master bedroom because it has a television. Every night, he eats dinner, watches CNN and then goes to bed.

Walter is considering a roommate, but grimaced after contemplating the idea aloud.

“Sometimes you have to say, ‘I don’t know if I’m ready for that,’” he said, as the light behind him illuminated the gray in his goatee.

For now, he has time to consider his options. He’s getting by — financially and spiritually.

Walter cooks for himself and makes sure the house is tidy because that’s what Gloria would have preferred.

He sometimes wonders why he didn’t die with the rest of his family. Walter hadn’t worn a mask when he cared for Gloria and Tasha and touched them while they were contagious. But he tested negative. He was left unscathed, another mystery of the coronavirus.

Tamika Darden-Thomas works with clients last month at the New Jersey Reentry Corporation. Patti Sapone | NJ Advance Media

As the first full year of the plague comes to an end, he personifies the stoic fortitude many survivors carry.

Tamika Darden-Thomas also embodies that resilience, something she says is endemic to the city.

“Newark is a unique city. We’re unique in our own right,” she said. “It’s just something about the fiber and makeup of the city.”

After the deaths of her grandmother and uncle, Tamika redoubled her efforts to help others in crisis.

So when a young woman having suicidal thoughts reached out to her in late September, she called a minister she knows and helped the young woman find a job in Pennsylvania.

“I tried to take my life twice — once as a teenager, once as a young adult,” she said. “And God, let me see it wasn’t my life to take, just so that I could be here to talk somebody else off of the ledge.”

But for many, the scars of COVID-19 seem permanent.

Coronavirus survivors Ray Palmer and Laura Bonas-Palmer. Patti Sapone | NJ Advance Media

Ray Palmer’s fever finally broke after nearly reaching 105. But the family’s ordeal with the coronavirus was not over.

Maya, his 14-year-old daughter, got sick soon after he did. She lost her sense of smell and developed a 102-degree fever.

“I knew what I (had) just gone through,” Ray said, composing himself after breaking down. “I wouldn’t wish that on my worst enemy.”

Maya recovered, but by then, the virus inflicted an emotional toll nearly as exacting as the physical damage.

“She’s scared as hell. She’s crying. He’s crying. And I’m crying, because we’re scared,” said Laura Bonas-Palmer, breaking down in tears.

COVID-19 has inexorably altered Al Jenkins’ life.

A ventilator helped him breathe for nearly three weeks. He was discharged from the hospital June 4, only to need nearly two months at a rehabilitation facility.

“He had to learn how to walk. He had to learn how to talk. Eat. Swallow,” Hameenah Muhammad said. “All of that was just unbelievable.”

By the time Al returned home, he had lost 60 pounds.

He has nerve damage on his left side from lying on it for so many days while on the ventilator, Hameenah said. Al still struggles to walk.

Hameenah has her own scars.

“I was so tired. It was very horrible,” she said. “Many times I cried because I was here by myself.”

So it is for Walter as well.

He tried to fight back tears at a vigil in late September for his wife and daughter organized by colleagues and friends.

The event was held outside the New Jersey State Offices building on Halsey Street. Gloria worked there as a building services coordinator for the state Division of Consumer Affairs. Tasha also worked in the building.

About 25 people attended, many holding balloons. Purple, white and silver balloons. Circular balloons. Letter balloons. Balloons shaped like angels.

The wind sent them swirling, still tethered to the hands of mourners. But once it stilled, the balloons spelled out “Gloria” and “Tasha.”

It would have been Tasha’s 34th birthday, so the group shouted, “Happy birthday Tasha!” and let the balloons loose. The mourners watched them rise above the skyline and float away.

Standing in front of the building, Walter choked up. After a brief pause, he swallowed back the tears and gathered himself.

His losses are still raw. But he’s trying to be strong for Gloria and Tasha.

Walter is still learning to live without his family.

This project was supported in part by the Center for Health Journalism at the USC Annenberg School of Journalism.

Walter Andrews wonders why he didn’t die with the rest of his family. He hadn’t worn a mask when he cared for his wife and daughter and touched them while they were contagious. Spencer Kent | NJ Advance Media

LEARN MORE

About the Authors

Reporting

Spencer Kent is a reporter covering health for NJ Advance Media. Follow him on Twitter @spencermkent or email him at skent@njadvancemedia.com.

Photography

Andre Malok is a multimedia specialist. He is a drone pilot and the host of “Outdoors with Andre.” Follow him on Twitter @AndreMalok or email him at amalok@njadvancemedia.com.

Photography

Patti Sapone is a multimedia specialist. Email her at psapone@njadvancemedia.com.

Editing

Jeff Roberts is an editor supervising health and education coverage. Email him at jroberts@njadvancemedia.com or connect on Twitter at @thejrob.

[This article was originally published by NJ Advance Media.]