Do Parks Push People Out?

Pendarvis Harshaw wrote this story while participating in the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism 2018 California Fellowship.

(Illustration Credit: Emeric L. Kennard)

Way back, decades before the current investigations and faked tests and lawsuits over the cleanup of the Hunters Point Naval Shipyard, people in southeastern San Francisco neighborhoods knew their ground and air was dirty. They worked on the Navy ships among the exposed asbestos, they breathed the emissions from the PG&E power plant, they heard the rumors about the nuclear waste poured down the sink at the radiation research lab just down the hill from the public housing. Once, a brush fire smoldered for more than a month underground, releasing wild blue and green smoke into the sky. They knew about the toxic dust kicked up every time a construction project rolled through, the smell of the rendering plant, and the kids who snuck through the fences to sit by the power plant outflow pond on the shore of the San Francisco Bay.

They also knew help wouldn’t come from outside. “Government agencies have a poor track record of keeping residents safe and healthy during the cleanups,” one Bayview–Hunters Point community newsletter concluded. “Taking care of residents while the cleanup and construction work happens is the main concern.”

So the people who lived here became informed and active. They gathered their own data. They led so-called “toxic tours” to show people the sites that jeopardized community health. They prepared reports showing what environmental injustice looks like: A 10 percent asthma rate in 2004 among Bayview–Hunters Point residents that was almost twice the national average. One in six kids with asthma. A rate of birth defects, 44.3 per 1,000 births, much higher than the 33.1 per 1,000 countywide. Infant mortality rates 2.5 times higher than the rest of San Francisco’s.

They led town hall discussions, started newsletters covering everything from housing developments to what fish was safe to eat, and held a “People’s Earth Day.” And by the 1990s they started to win. A proposal for a second power plant was shut down. The Port of San Francisco abandoned a proposal for a new shipping terminal. The EPA and Navy started the Superfund cleanup process at the former naval shipyard. The EPA’s Brownfields Program authorized numerous localized cleanups. And in 2006 PG&E closed its Hunters Point power plant and the long road to site cleanup began.

This summer, I joined nine high-school and transitional-age kids from the neighborhood to tour their southeast San Francisco backyard, to walk toxic ground that connects the local fight for environmental justice with their futures. The young folks, interns with the group Literacy for Environmental Justice, are spending the summer gathering air quality data in their neighborhood, because as LEJ community programs manager Anthony Khalil tells them he’s learned in nearly two decades of work in this corner of the city, “it doesn’t mean anything until we can come together, get organized, and share this data.”

Khalil co-captains the tour and drives the van. Riding shotgun is Raymond Tompkins, who is commonly referred to as “Dr. Raymond,” an elder environmental activist and former chemistry teacher who claims to be retired, but hasn’t stopped teaching yet.

I ride in the back with the interns. Present, but unmentioned, is a shared understanding that as the battle for clean air, soil, and water carries on in the Bayview, another threat looms. We all know the numbers, and we all know we are touring a lot of toxic places whose cleanup—if it happens—and redevelopment will change this neighborhood’s character and displace many existing residents, including perhaps these kids.

The tour starts as we pull out of LEJ’s headquarters at the Candlestick Point Community Garden, where Tompkins sounds the first note about the future. “You have Candlestick,” he says. “In the next 20 years, that property is going to be worth $100 billion.”

“100 billion?!” I say, overly pronouncing the b.

“Yes, sir. Not million, billion,” Tompkins confirms.

Heading north, continuing through the neighborhoods that follow the shoreline in Bayview–Hunters Point, we wind around Yosemite Slough, where California State Parks and the EPA have worked for a decade to clean up toxic soil from nearly a century’s worth of sewage, dumping, and industry. Behind chain link construction fences, a trail now leads out past a few muddy artificial islands for nesting birds. The narrow inlet widens into a curving stretch of the Bay, separating the public housing projects in the Double Rock neighborhood from the south edge of the Hunters Point Naval Shipyard.

The 500-acre shipyard is a Superfund site with a two-decades-long, scandal-ridden history of cleanup of radioactive material, most recently slowed down by the discovery last summer that a portion of the site’s clean soil sample results were falsified. Tompkins shows us the place where the blue-green fire burned and the former lab where workers poured nuclear waste down the sink. As we exit the shipyard we see a giant magenta billboard with the logo for developer FivePoint in one corner and “Come Back Soon” in big letters.

A few minutes later Khalil pulls the van onto a freshly paved surface that overlooks India Basin, the inlet north of the shipyard, and parks. The kids jump out of the van and stand firm in their Nikes on the cement yard adjacent to where the PG&E power plant’s cooling pond once stood. At the moment, the pavement is used as a community event space by the group Now Hunters Point. But that’s a temporary setup.

“What’s next?” Khalil asks the group. A bike rider casually coasts past in the distance toward the restored wetland park at Heron’s Head. “How do you develop this in a way that’s not only environmentally sustainable, but is just for existing communities?”

I don’t think the question is rhetorical, but it doesn’t garner an answer from the teenagers. Khalil continues, “I personally have this feeling, and I bet you all would agree with me, that we have a long way to go.”

“When we look at this site,” Tompkins says, “we not only look at the victory as well as the challenge of shutting down the power plant, but we also look at how the neighborhood develops and builds up.”

Listening to Tompkins, I think about the people who have lived here over the past seven decades and have made this place. Bayview–Hunters Point, the southeastern chunk of San Francisco east of Highway 101 (or more officially ZIP code 94124), is the city’s last major African-American neighborhood. Many of them moved here from the South to build ships during World War II and until the last few decades made up more than 65 percent of the neighborhood’s population. They were once relegated to this neighborhood by redlining and housing covenants, and they made the most of what they were given. They were and are blue-collar workers, who labor in factories and plants. They were and are artists who serve as culture keepers, amplifying the story of a people on the backside of the most scenic city in the world. Despite being disregarded by local and federal governing bodies—not to mention overly policed—the effort put forth by the people who care about this community laid the foundation for what’s next in southeast San Francisco.

The official “next” includes more than 13,000 new homes split between two major developments. At least 75 percent of those homes will sell as market-rate luxury units, which will more than double the number of housing units in Bayview–Hunters Point. So once it’s cleaned up, who will live here in two decades? Who will shop in the planned 700,000 square feet of commercial and retail space and work in the 3 million square feet of research and development space between Candlestick Point and the Bayview? Who, a lot of residents ask when they look at those numbers, is this cleanup really for?

I got a hint after I plugged the shipyard’s developer, FivePoint, into an Internet search query and started to get targeted email and social media advertisements for tours of their new luxury homes. The marketing images show modern glass-and-earth-tone housing, with just a couple of horizontal wooden slats on the exterior— because what says “new development” more than those damned wooden slats?

What this cleanup and overhaul is for, according to the city, is a once-in-a-generation development integrated fully into an urban ecological utopia. The city, developers, and park advocates envision a 13-mile “Blue Greenway” from where the San Francisco Giants currently play baseball, at AT&T Park on China Basin, south to where they used to play, at Candlestick Park. “Think ‘Crissy Field meets the High Line,’” the San Francisco Parks Alliance page introducing the Blue Greenway plan reads, as an introduction to its park-and-nature-centric ambition for these neighborhoods. “Could an Overlooked Cove in San Francisco’s Bayview Become the Next Golden Gate Park?” a KQED headline asked in August.

Developer renderings for Candlestick, the Shipyard, and India Basin show parks connecting all the new housing developments to each other and to the Bay. The Blue Greenway map shows native plants and birds where once there were industrial plants and warehouses. Wetland-fringed shoreline parks feature prominently along the entire Blue Greenway, connecting residents to the regional goal of a restored San Francisco Bay. At 900 Innes, a former industrial site now owned by the city’s Recreation and Parks Department, federal government brownfield grants will help clean up and fill the largest remaining gap in the San Francisco Bay Trail—connecting India Basin developer BUILD LLC’s proposed “Cove Terrace,” a “prominent public-private plaza, lined with active ground-floor restaurants and cafes,” to the India Basin Shoreline Park and a new public pier and kayak launch site.

The end of my toxics tour takes place just up the street from where that new pier will be. We stand in a group looking out at Heron’s Head Park, where the Bay Trail picks up again and leads out to the water. A few terns fly over the blue-green water of the former power plant cooling pond. The sound of the offshore breeze is overwhelmed by the noise of construction trucks laboring in the distance, building a future for this neighborhood that looks nothing like what it is now.

“Who is it for?” Tompkins asks.

One proposal for redeveloping 700 Innes Avenue in San Francisco’s India Basin includes a “mixed-use village with retail shops, apartments, and townhomes intricately linked to a 6-acre park along the shoreline.” (Design drawing from San Francisco Planning Department)

Marie Harrison, who has “lived, worked, and played” in the Bayview since she first moved there as a teenager in the late 1960s, says that whoever the greening of the neighborhood is for, it’s not for her or her children and grandchildren. “They call it ‘green’ to give it a more natural kind of a feel,” she told me by phone from Stockton, where she moved two years ago. “To me, it’s more or less the idea of moving folks out and replacing them with new folks. With us in particular, it’s all about gentrification. I don’t care what you call it. You can dress it up and give it a new name if you like. But it still boils down to gentrification.”

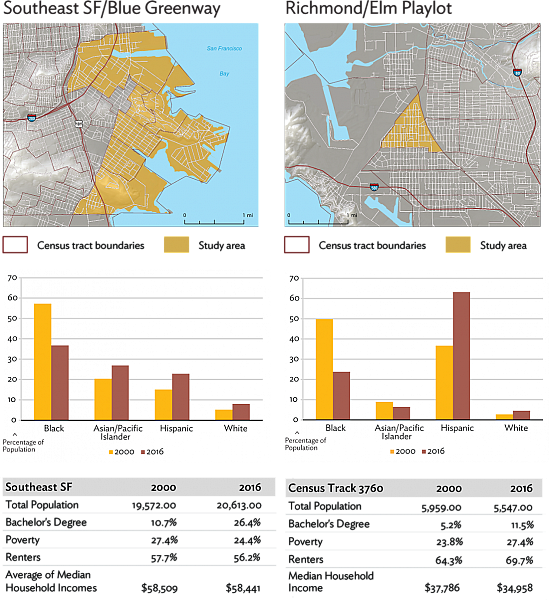

Academics have coined the term “green gentrification” to describe the phenomenon in which environmental cleanup, restoration, and neighborhood greening prepare the ground for displacement of existing communities. It sums up what some residents say is beginning to happen in southeastern San Francisco, and how more universally the arrival of parks or cleanup of legacy pollution isn’t always fully welcome. For some, new parks can feel no different than tech shuttle stops or gastropubs: a signal that they are about to see a lot of richer, whiter neighbors. Green gentrification has already happened, or is a source of tension, in urban enclaves around the United States.

Along the Los Angeles River, for example, community organizations have formed to fight riverside gentrification as the city maps out restoration of the 51-mile river path. In Washington, D.C., longtime residents of the Anacostia River have filed a class action lawsuit against the city, claiming its plans to “alter land use” and lure millennials to the area through luxury waterfront housing and parks constitutes discrimination against the current, older black community. In the recent Resilient By Design competition around the San Francisco Bay, designers proposed community housing trusts to protect residents from displacement as the region deals with sea level rise. In perhaps the most famous case, the High Line in New York City transformed an abandoned railway to a green pathway park, changing the neighborhood character entirely. “The High Line,” a New York Times op-ed by Jeremiah Moss, author of Vanishing New Yorkdeclared, “has become a tourist-clogged catwalk and a catalyst for some of the most rapid gentrification in the city’s history.”

Even the High Line’s developers now say their project is something of a cautionary tale; in 2017 High Line Executive Director Robert Hammond started a website called The High Line Network to advise how similar projects might restore land without disrupting surrounding neighborhoods. In a 2017 interview with Fast Company, Hammond said, “When we opened, we realized the local community wasn’t coming to the park, and the three main reasons were, they felt it wasn’t built for them, they didn’t see people like them there, and they didn’t like the programming.”

It’s not that parks necessarily cause gentrification. But the way they’re designed and built hints at the future of the neighborhood, as evidenced by the ambivalent attitude toward the Blue Greenway I heard from the longtime Bayview–Hunters Point activists, residents, and community organization member and leaders. Look at those redevelopment drawings closely and ask who they’re for, and one’s whole perspective may shift. When Tompkins was highlighting the capital-B-billion-dollar value of that shipyard development, he was calling our attention to the big-picture forces shaping the future here and what it likely means for people who live here now, especially the renters who make up 48 percent of the Bayview–Hunters Point ZIP code.

“Parks are not discrete spaces,” says UC Santa Cruz sociologist Dr. Lindsey Dillon, who has spent more than a decade researching environmental justice in Hunters Point. “If you build parks but are not protecting people from market forces, which in San Francisco are so rampant, then parks are going to become unwitting participants in displacement. It’s not about intentionality, or about parks per se. It’s about urban planning more broadly.”

In other words: Of course people want parks in their neighborhoods. But they told me repeatedly that they want the parks to be built for them. At the most basic level, that means proceeding with extreme thoughtfulness. It means, Bayview activists say, beginning with a toxic cleanup that hews to the same standards as those in Crissy Field, San Francisco’s 78 percent white Marina District. To people like Marie Harrison, it means incorporating job training for neighborhood residents in park development, designing parks with widespread local consensus, and building them with local workers. And it means not conceiving of them as amenities to increase the sales point on soon-to-be-built luxury housing, as some Bayview residents told me they see the Blue Greenway’s parks.

“It would be positive if they cleaned up the parks and made them really nice and left open space, because it used to be a community of children,” Harrison says. “Unfortunately, the plan is to tear down and make walkways. To tear down all of the old buildings, to partially clean—or clean what they only have to. Put grass over it. And make a few docks and restaurants where people with boats from as far away as Oakland, Richmond, and San Jose can sail up and pull over at Innes Avenue and have lunch or dinner. Nice restaurants and music areas, stroll through the wetlands and that kind of thing. And I’m thinking, ‘Wow. How many folks do you know that live in public housing, personally? And how many of them do you know own boats?’”

The complexity of remaking the Bayview–Hunters Point shoreline can’t be overstated, with multiple Superfund and Brownfields cleanup projects underway and three commercial developers, at least half a dozen city agencies, numerous advocacy organizations, and the public all involved. The Blue Greenway has been intertwined with the redevelopment since the city, under then-Mayor Gavin Newsom, launched a Blue Greenway task force in 2005 and tried to include a wide swath of input from interested parties: more than 16 different public agencies, more than 40 neighborhood associations, nonprofit entities—including environmental advocates SPUR, the Bay Trail and the Trust for Public Land—businesses, and concerned residents. Among the many goals laid out in the Blue Greenway task force document “Vision and Road Map to Implementation” is “build community support.” It’s stressed repeatedly.

The San Francisco Parks Alliance (the driving force behind the Blue Greenway), the developers Lennar and BUILD, and the San Francisco Recreation and Parks Department have held hundreds of community meetings over the last decade. They say they’ve shaped their plans accordingly.

“I don’t think our organization thinks that investing in a neighborhood in a positive way creates displacement,” SFPA Chief Executive Officer Drew Becher told me. “It’s like people saying you shouldn’t have nice things.”

The SFPA, a nonprofit that advocates for the city’s parks, has helped secure more than $38 million for the Blue Greenway. Becher says SFPA has invested in numerous community gardens and residential parks in San Francisco and seen, in fact, increased sense of community and no displacement. That’s what he expects now from the redevelopment of southeastern San Francisco, he told me.

“The Blue Greenway was made to benefit every neighborhood it touches and the entire city,” Becher said. “I strongly believe that every community wants to have great open space, and that’s what we’re advocating for.”

Ultimately, Santa Cruz sociologist Dillon says, whoever will feel represented by the Blue Greenway comes down to who thinks their concerns were addressed. At this point, Dillon says about who feels heard, “Longtime black or southeast Asian Bayview residents, probably not—no one that I know feels that way.” One of Dillon’s dissertation chapters, which she’s now turning into a book chapter, focuses on attitudes toward Heron’s Head, the restored wetland park built on top of the cleaned-up rubble of a shipping terminal. Conservation groups that have helped steward the park through its restoration see it as an environmental justice victory, a place where birds and native plants have conquered formerly toxic waste and where it’s surprising that more local residents don’t visit. Conservationists, Dillon writes, tend to see the nature in the park as redemptive, purifying, separate from the industrial or human processes in the surrounding neighborhoods. Many local residents Dillon interviews, though, don’t separate the park’s long, complicated history—which they’ve lived through and been a part of—from its present so easily.

“To my mind,” she writes, “these diverging opinions of the wetlands also reveal the complex relationship between the nature projects and the market-driven redevelopment process in Bayview–Hunters Point, which many residents experience as a form of displacement, and connect with a longer history of racism in San Francisco.”

Long-time Bayview–Hunters Point resident Harrison explained divisions within the community this way: “When you sit a room full of poor folks on one side and homeowners on the other side, who are trying to bring all of this quote-‘greening’ into our areas, and trying to pass if off as something that’s going to be good and healthy for you, and you can’t see through that? And I’m saying, ‘Good Lord! We’re black, we’re not stupid.’”

You can ask the same questions of all redevelopment projects, green and otherwise. Who’s making the decisions, and who’s getting what they want, and who is being represented, and whose urban planning aesthetic is the priority?

Staff for San Francisco Board of Supervisors President Malia Cohen, who has represented Bayview-Hunters Point for the last eight years and is described on the Blue Greenway web site as a “dedicated champion of the Blue Greenway,” did not respond to repeated requests to discuss the project.

San Francisco isn’t alone in facing these questions. The Bay Area’s housing crisis and high number of renters make residents here particularly susceptible to displacement of any kind. From restoration and park enhancement on the Guadalupe River in San José to street tree planting in East Palo Alto, to shoreline restoration and creek daylighting projects throughout Alameda and Contra Costa counties, the same question hangs over the work: Who is this for?

Across the Bay from San Francisco, in the flatlands of Richmond, a woman named Toody Maher stands in Elm Playlot wearing a shirt that reads “Pogo Park” on the lapel. “We’re a nonprofit in Richmond,” says Maher, the organization’s executive director. “We worked with community residents to reclaim this park.”

Maher is in the green picnic area as she describes what the park used to be like. “First of all, all of the houses around the park were boarded up and abandoned,” she says. “And people were squatting and living in them, and men were coming to the park all day to just drink. The park was nothing but broken glass. People used to bring their dogs to fight or train.”

She says the city installed a quarter of a million dollars’ worth of new play equipment in the early 2000s, “and within weeks, people tried to burn it down.”

Then Maher’s Pogo Park came and announced its interest in adopting the park from the city. They signed an agreement, allowing Pogo Park to work with the city closely, but, as Maher says, “we were allowed to reimagine the park with the community.” This let Pogo Park employees and local residents design the park’s barbecue grills, trash cans, and even a custom fence with cutout profiles of the people who worked on it. They designed it all at a local fabrication laboratory—the same one that made the humongous glove in the outfield of the new Giants ballpark in San Francisco, overlooking the northern limit of the proposed Blue Greenway.

Inside the Pogo Park office in Richmond, which was once an abandoned house adjacent to the park, there are photos of community members welding the equipment for the park. “We bought the house next to the park, and got a $300 fridge from craigslist, and started serving lunches out of it,” Maher says. “We’ve served like 12,000 meals.” Pop-up events helped bring the park to life, slowly building momentum in the community. In 2006, California voters approved Prop. 84, a $5.4 billion bond that included $490 million for park improvements, and Pogo Park won a $2 million grant from the state to build the park the way Maher says all parks should be built—involving the community in every step from start to finish.

Pogo Park’s head of research, Joe Griffin, explained how the towering plane trees in the park stand as a metaphor for Pogo Park’s approach to working with the community. The trees signal who the park is for. “It wasn’t just replacing the beauty that’s already in the neighborhood, but adding to it and uncovering it, so it could actually grow,” he says. “Which is the same thing we’re trying to do with the community itself: We’re not trying to replace people, we’re trying to work with the strengths that we have.”

Richmond residents helped design and build the amenities at Elm Playlot — including a fence with profiles of those who helped build the park — as well as create the programming for kids and adults. (Photo by: Pogo Park / Bay Nature Magazine)

What’s happened in Richmond’s Elm Playlot also has a name in academic circles. In a 2012 paper about environmental gentrification in Brooklyn, Dr. Winifred Curran and SUNY Buffalo geographer Trina Hamilton looked at what they describe as a different model of urban redevelopment. In the Greenpoint community, longtime residents were actively involved in reshaping their neighborhood. “Neighborhood residents and business owners seem to be advocating a strategy we call ‘just green enough,’” Curran and Hamilton wrote, “in order to achieve environmental remediation without environmental gentrification.” The phrase has become a rallying cry for many community advocates.

“The ‘just green enough’ strategy depends on the willingness of planners and local stakeholders to design green space projects that are explicitly shaped by community concerns, needs, and desires rather than either conventional urban design formulae or ecological restoration approaches,” UC Berkeley College of Environmental Design Dean Dr. Jennifer Wolch and colleagues Dr. Jason Byrne and Dr. Joshua Newell wrote in a journal article in 2014. In a conversation at her office in Berkeley, Wolch told me that it’s not just about drawing up blueprints for housing and showing up from another part of the city to plant native plants. “Part of the process has been heavy community outreach,” she said.

As environmental justice has become more explicitly part of legislation, the calculus in other developments has started to change. I talked to Rico Mastrodonato, a senior government relations manager at the Trust for Public Land, who helped write equity policies into the state’s newly approved park funding bond, Prop. 68. Mastrodonato is not convinced creating parks in urban areas causes displacement. A resident of the Mission District for the first 20 years of the tech boom, he thinks San Francisco’s gentrification issue has more to do with skyrocketing tech salaries and a lack of renter protections. “Parks are not amenities,” he says. “They help lower emissions that contribute to climate change. They help the social fabric of communities, and they provide recreational and quality-of-life benefits that are extremely important.”

But he does note that community involvement in the development of urban parks is essential: “If you don’t have community involvement in the park, it’s a failure. The park has to be a reflection of the community. They have to help with the design of the park. If you get that, and you really take seriously community participation, then they take ownership over it. They care about helping to maintain it.”

Tonie Lee, who works with Maher at Pogo Park, is one of those community members photographed using welding tools to build pieces for the park. Lee said she used to play in the park as a kid; she’s happy with how the park has changed and how the formerly boarded-up houses in the surrounding community are now housing families instead of vagrant drug users. But she has noticed that even positive change comes with a cost.

“This house right here was up for sale,” says Lee, pointing to a building just across the street. “On their website and on their flyers, they included the park as promotion to sell their place.” She was dismayed.

“That was one of our big things, like, ‘Really, they’re using it as advertisement?’ They never did come and even give a dollar as a donation or anything, but you’re using it to promote the sale of your place?”

It’s hard in some ways to compare Central Richmond and southeastern San Francisco. There are enormous market forces and decades of individual history acting on each. But these tensions around housing, parks, and the future are shared. It was striking to me that one community has mostly embraced its park, while another community continues to organize to prevent the future “green” vision from arriving. (Various Bayview–Hunters Point community groups plan to create a “Save Bayview Hunters Point Coalition” specifically to fight gentrification in the future Blue Greenway.) It was striking to me that in Richmond, Pogo Park set up in a house next to the park and asked community members to weld playground equipment, while in San Francisco, Marie Harrison told me, one park hired an outsider to paint African-motif art on the walls. Maybe you can’t directly compare the neighborhoods or their parks. But the more you compare the process, the way they’ve gone about building a greener future, the more it’s clear who they’re building for.

A few days after visiting Pogo Park, I met with Joe Griffin at a cafe in Berkeley. In addition to his Pogo Park role, Griffin is a Ph.D. candidate at UC Berkeley’s Institute of Urban Regional Development. He says he hasn’t seen Pogo Park mentioned in any real estate ads, but he’s interested in seeing more resources come to the community—so as long as it’s done properly: “We want people to come and invest, but not at the cost of displacement of all the families … You see so many other neighborhoods where they’re not being able to enjoy the fruits of their labor.”

Much like Bayview–Hunters Point across the Bay, the community around Richmond’s Pogo Park has seen its share of environmental injustices. It’s in Richmond’s Iron Triangle—where there’s a crossing of three train tracks. Toxic clouds from the Chevron Richmond Refinery can float by with a simple gust of wind. The city and residents sued the refinery for emissions released during a fire in August 2012; the case was settled earlier this year, with Chevron agreeing to pay $5 million.

“All of those environmental pollutants are in the area, but to an extent, it’s become normalized,” Griffin says. “I grew up in Richmond; everyone had asthma. I went to college, everyone doesn’t have asthma. What’s going on?”

Griffin says the focus of his studies at UC Berkeley is the health impact of the public redevelopment of Pogo Park, particularly toxic stress (suffered for elongated periods, often during formative years) within members of the community. He plans on using mixed methods, data and experiences, to tell the full story. He’s just getting started collecting statistical data and where he’ll present his findings is still to be determined. But it will definitely include a presentation at the park, open to all community members who are available to come.

Before we part ways, I had to ask Griffin the question at the center of my study: How do you revitalize a neighborhood and keep people there?

“That’s a huge question … I think that plays into a lot of the fear when you see something in a neighborhood revitalizing,” says Griffin. “In the neighborhood I’m from, when we started seeing bike lanes, we were like, ‘Wait a minute, why are there bike lanes there? Why did they fix those light poles and what is that bench doing here?’ You get scared.”

He says that even though working to improve the community could price out longtime residents, it didn’t stop the Pogo Park team from making the community better. It was their project.

And then he noted the most important piece to the puzzle about including a community in redevelopment plans: “It can have an effect on the social environment—how people are connected to each other.” Griffin turned into a bit of cafe orator as he continued. “And it can affect the economic environment—that’s the importance of having staff members who are also local residents—and being able to pay them, so it’s not just a nights and weekends thing. This is a part of what they do and how they feel financially secure in the neighborhood. It affects place in a lot of different ways.”

[This story was originally published by Bay Nature Magazine.]