Dreamers in search of affordable health care (Part 1)

This article was produced as a project for the California Health Journalism Fellowship, a program of the Center for Health Journalism at the USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism.

Other stories in the series include:

Nidia Torres, 34 with her four-year old daughter said DACA has provided her great opportunities, in this country, which she consider home. She just needs to find an option for medical insurance. (Courtesy of Nidia Torres)

Click here for SPANISH version.

June 15, 2012 was a historic day for thousands of young immigrants who under President Obama’s executive action became eligible for temporary relief from deportation.

“These are young people who study in our schools … they pledge allegiance to our flag. They are Americans in their heart, in their minds, in every single way but one: on paper,” said Obama when he introduced Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA), a program making nearly 1.5 million youth brought to the country illegally as children eligible for a reprieve from deportation and a work permit, both renewable every two years.

Over 853,000 immigrants between the ages of 16 and 31, often referred to as “dreamers,” have applied for DACA status since the president’s announcement. For many, with the ability to work legally came the hope of higher wages and perhaps benefits.

Getting health insurance, however, has not been easy for some. For others, it’s not a priority.

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) enacted in 2014—commonly known as Obamacare— excluded DACA recipients from coverage because they are not permanent legal U.S. residents or citizens.

In this three-part series, EGP looks at some of the challenges this group of dreamers face in their search for affordable health care and the options they have to access services.

DACA and Obamacare: Who Qualifies?

Los Angeles resident Nidia Torres was brought illegally to the U.S. when she was six years old. She lived in the shadows for over two decades, hoping not to be discovered or deported back to Mexico, a country she does not call home.

In 2013, everything changed. Torres was granted DACA status and excitedly started planning for the future. The opportunities a work permit, driver’s license and social security number would bring to her life were endless, including providing a better future for her U.S. born daughter, Torres told EGP.

“No more shame for being undocumented,” she recalls thinking when her work permit arrived in the mail.

Torres soon landed a job waitressing at a national restaurant chain where she was paid minimum wage plus tips, but did not offer health insurance.

“I can work legally, my daughter has Medi-Cal, so I think I’m OK,” she told EGP, explaining that after years of low-paying jobs and long hours that left her little time for her daughter, the new job was a big step forward.

“I just wanted a job,” she told EGP. “Plus I don’t really get sick,” so health insurance was not a big deal, she said, adding she had no idea where to get coverage on her own.

Torres, who speaks both English and Spanish and has some college education has since been promoted to manager and is earning more money, but still has no health benefits.

The goal of the Affordable Care Act was to increase “the quality, availability, and affordability” of private and public health insurance to the then over 44 million uninsured Americans, providing they are legal permanent residents or U.S. citizens. To keep costs down, large numbers of young, healthy individuals — the same group targeted by DACA — would have to be enrolled, yet undocumented immigrants and DACA recipients are ineligible to buy health coverage through government sponsored health exchanges or receive premium tax credits or other savings on marketplace plans, even though they pay into the tax system.

Gabrielle Lessard, a health policy attorney with the National Immigration Law Center, calls the policy unjust. DACA recipients are working and paying taxes for a service that they can’t apply for, she told EGP.

“The exclusion of DACA recipients probably increases the price of insurance for all other people,” Lessard said.

In California, however, some low-income undocumented immigrants and DACA recipients may qualify for Medi-Cal, a state funded health insurance program for low-income families, people with disabilities, pregnant women, children in foster care and low-income adults who meet certain requirements.

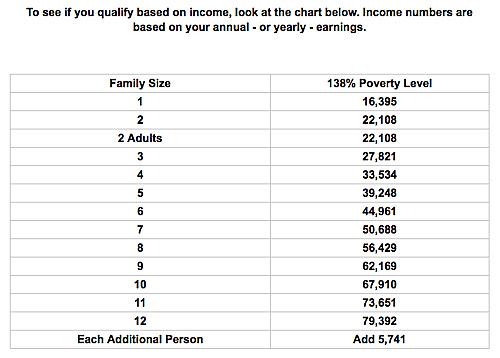

Torres is not one of them. According to the California Department of Health Care Services and federal eligibility requirements, Torres’ $23,000 a year income puts her just slightly above the $22,108 maximum Federal Poverty Level (FLP) for a family of two, making her ineligible for Medi-Cal.

Like many other DACA recipients with incomes “too high” for health insurance subsidies, Torres’ options for health coverage are limited, and the process for finding affordable coverage can be complex, according to the UC Berkley study, “Realizing the Dream for Californians Eligible for Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals: Health Needs and Access to Health Care.”

Many DACA recipients don’t even know they have options, the study found. The lack of information reflects “the complexity” of the network of programs available and the process to access them, researchers stated.

Getting health care doesn’t have to be a problem, says Irene Holguin, director of community relations with Arroyo Vista Family Center, a network of five clinics serving the east and northeast side of Los Angeles.

During a free family health fair Friday at Arroyo Vista’s clinic in Lincoln Heights, Holguin told EGP there are options for everyone, regardless of immigration status or income.

When people arrive at one of our clinics for the first time they undergo a financial screening to determine what types of programs they are eligible for, she said. “We don’t turn anyone away,” she added. She explained that the clinic offers discount programs and fees to those who do not qualify for state or federal funded program.

For example, if a patient can only pay $10, Arroyo Vista will help them set up an affordable payment plan for the balance, Holguin said.

The Arroyo Vista clinics provide primary health care in communities where approximately 98% of families are Latino and many of them low-income, explained Holguin.

“There’s a lot [more] that needs to be done in regard to informing the community and encouraging people to be proactive and seek preventive health services,” she said, “because a lot of people have illnesses that they don’t even know they have.”

As for Torres, she told EGP she would be open to going to a clinic like Arroyo Vista to look into her what her options are. “Better safe than sorry,” she said.

Part 2 of the series will look at the pitfalls of applying for coverage for those living in mixed-status households.

[This story was originally published by EGP News.]