On Jan. 1, 400,000 Virginians who otherwise could not qualify for health insurance became eligible for Medicaid.

Republican lawmakers for years had blocked Medicaid expansion. Then last year, an influential delegate from Virginia's coalfields changed his mind.

On a dank September Sunday, autumn’s fog shrouded Lee County’s mountains and quickened the steps of people filing into the high school’s gymnasium.

Some had slept in the parking lot so they’d be ready for the start of Day 2 of the Remote Area Medical Clinic.

Their mouths hurt. Their vision was fuzzy. Their blood pressure was high.

They were mostly folks who work hard but earn little. They couldn’t afford health insurance premiums or the sliding fees charged at federally qualified health clinics.

The RAM clinic offers primary care, dental work, vision checks and glasses, and, depending on who shows up, other services such as flu shots and kits containing the antidote to opioid overdoses, along with demonstrations on how to use it.

Long rows of folding chairs lined a hallway. People scooted from one chair to the next as they moved closer to entering a classroom for a vision check. Only a few had heard that Medicaid would soon expand; the others spread word along the line, wondering if it would help them.

“Will I be eligible? I sure would like that,” said Marsha Ritchie of Stickleyville. The 54-year-old babysitter relies on the annual RAM clinic for her health care. The rest of the year, she does without.

She’s one of Del. Terry Kilgore’s constituents. The Republican leader has represented Virginia’s far southwest corner for 25 years.

Until recently, he didn’t understand all the social and economic dynamics that contribute to the ill health of his people.

Kilgore fought Medicaid expansion for years because he thought it was just government getting bigger. He waited for Congress to repeal or amend the Affordable Care Act. That didn’t happen. But then he saw the difference federal money was making in other states that had expanded Medicaid while his constituents couldn’t access primary care, let alone specialty care.

It was a connection that came when, as chairman of Southwest Virginia Health Authority, Kilgore had to decide whether to allow a merger between the coalfield’s two ailing hospital systems.

Kilgore’s constituents, especially those involved in health care, used the opportunity to educate him about what it means when people can’t afford to pay for doctor visits. With too few paying patients, fewer doctors can afford to practice in the region, which then causes shortages for people who have insurance. And when people delay getting care, diseases progress and subtract years from their lives and add to the cost of treatment.

“We basically said to him if Medicaid isn’t expanded, more people will suffer. And he said this is a party issue, but then he sat there for a minute and said, ‘Are the kids OK? Are there kids who are hurting because of this policy?’ ” said Wendy Welch, executive director of the Southwest Virginia Graduate Medical Education Consortium. “It was a moment you could see straight into someone’s heart. ‘Are the kids getting taken care of?’ And I’d like to think that was one of those moments when he started believing if a flip could happen that didn’t completely alienate the whole political system in Virginia, that it was a good thing to do.”

Kilgore said he came to understand that “if you don’t have a healthy work force, or health opportunities for individuals to receive treatment, then you aren’t going to be able to recruit businesses or create jobs. You’re not going to be able to convince our children to stay here.”

To his legislative colleagues, he portrayed it as an economic development issue.

“Our hospitals are suffering, and our people are suffering. We didn’t have a healthy work force, as we found out. So I just decided, hey, somebody has to step up and say what needs to be said,” he said.

“Our hospitals are suffering, and our people are suffering."

With that conviction, Kilgore brokered a deal in the General Assembly to expand Medicaid in Virginia. A work requirement provided cover for enough members of his party to join Democrats and break the blockade that had kept the state with one of the most restrictive programs in the nation.

The federal government will pay 90 percent of the expansion’s cost, about $2 billion a year, and Virginia’s hospitals agreed to pay an assessment that funds the difference. In exchange, the hospitals will get a higher reimbursement rate from Medicaid.

Until Jan. 1, adults could not qualify for Medicaid unless they were old, disabled, pregnant or caring for the young or infirm — and also very poor.

This kept 400,000 Virginians — the majority with jobs — from having the means to pay for health care as they earned too little to purchase policies through the Affordable Care Act exchange. In Kilgore’s district, those without insurance turn to charity care, such as RAM clinics, or to hospital emergency rooms that are required by law to treat them. The bills often go unpaid, impacting community hospitals’ ability to stay solvent.

“Republicans should be about helping people who are trying to help themselves. We should be about that. We should be about healthy populations. That’s something we all should be about,” he said. “I have folks who disagree vehemently with me on that. But I think this is a way, especially in the rural parts of the state, that we can provide the access to health care and afford our folks the ability to live a healthier lifestyle, so I just think that’s what it needs to be about. Not whether it’s some government program or not. The government program is going to be there.”

Folding chairs line a hallway at Lee County High School during a RAM Clinic in September, filled with people waiting for vision care. Michael Mannon, 50, of Jonesville and Michelle Ely, 48, and her 12-year-old son, Michael Ely, who live in Dryden, move along the chairs as they wait to enter a classroom and have their vision checked. (Photo Credit: Heather Rousseau/The Roanke Times)

New eligibility

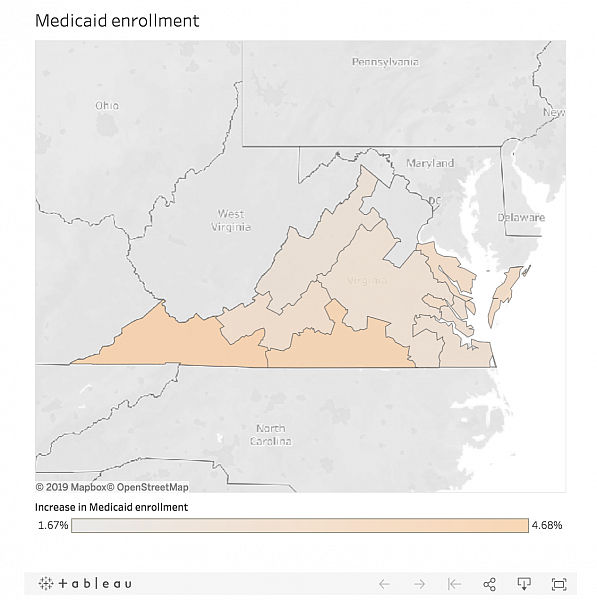

In November and December, more than 200,100 Virginians signed up for Medicaid under the new rules and had coverage starting New Year’s Day. Most live in Northern Virginia or near Richmond.

Kilgore’s constituents live in the farthest corner of Virginia along the state’s mountainous spine and are included in the Department of Medical Assistance Service’s southwest region. By Jan. 4, more than 15,700 of the newly covered adults lived in the state’s 10 westernmost counties.

Enrollment is continuous. Virginia reached out to the most populous areas first before spreading word to rural areas in December, so the numbers are expected to continue to climb as word spreads.

The Department of Medical Assistance Services did not sponsor an information booth at the September RAM Clinic in Lee County. Spokeswoman Christina Nuckols said the agency wasn’t ready to take applications and did not want to confuse people by having them apply too early and be rejected.

Cheryl Howe wondered if she’d qualify. She was rejected once before because she had a job. She lives in a trailer on a friend’s Lee County farm and drives more than an hour to her customer service job in Kingsport, Tennessee, where she earns $10.50 an hour. The call center offers insurance, she said, but she can’t afford the $400 monthly premium.

This was the first time she’d visited a RAM clinic. Remote Area Medical is widely known for its giant event held each summer on the Wise County Fairgrounds in partnership with the Health Wagon. Thousands of people travel from all over to gain access to specialists; national media drop by to show what charity care looks like — such as people getting their teeth pulled in a fairground’s barn — and politicians stump on health care policy.

Most RAM clinics are like the one held each year at Lee County High School, offering basic medical care along with dental and vision services to a few hundred to a thousand people. Each clinic differs somewhat depending on the organizing partners’ focus and ability to recruit volunteers.

The University of Buffalo’s dental school brought so many volunteers to Lee County that the wait time was short. Clinic organizers, seeing they’d have more help than patients, spread word on local radio and social media and through churches.

Howe heard she could see a dentist. Her mouth was sore, and she figured five, maybe six, teeth needed to be pulled. First she had to wait on the bleachers until her blood pressure fell.

“I told them it would be high,” she said. Howe found out two months earlier that her blood pressure was dangerously high when she went to an emergency room in Kingsport with severe cramps and bleeding.

She had stopped menstruating some years before. She said she was given an ultrasound, told that her uterine wall was too thick and that she should have additional procedures.

“They wanted to do a D and C, but they couldn’t do a D and C because I don’t have insurance,” she said. So she was given a prescription for the bleeding, and a prescription for hypertension. She was able to fill both generics cheaply. But when the blood pressure medication ran out, she couldn’t get more without a new prescription, and she didn’t have the $60 fee required to drop by a health clinic.

Once her teeth were seen to, Howe said she’d go to the clinic’s doctor or nurse practitioner to see about a prescription.

Howe wanted to know more about Medicaid expansion but figured she’d have to wait until she could get to the library since she doesn’t have a cellphone or internet access at home, nor the ability to get it even if should could afford the service.

Nursing student volunteer Chelsey Lewis of Jonesville retakes a blood pressure reading for Cheryl Howe, who lives on a farm near Jonesville. Howe was waiting to have teeth pulled but was not permitted to enter the dental clinic until her pressure fell. She was diagnosed with hypertension a few months earlier when she went to an emergency room for abnormal bleeding and cramping, but she could not afford to go to a primary care clinic to get a prescription. (Photo Credit: Heather Rousseau/The Roanoke Times)

Unhealthy lives, early deaths

Howe’s challenges are commonplace in Virginia’s coalfields.

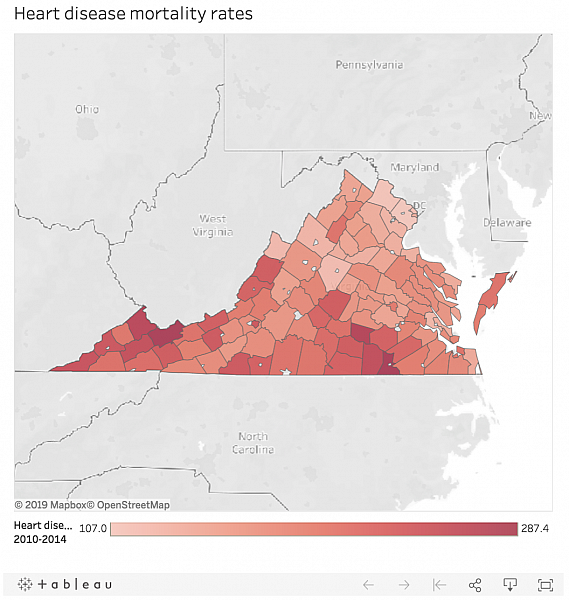

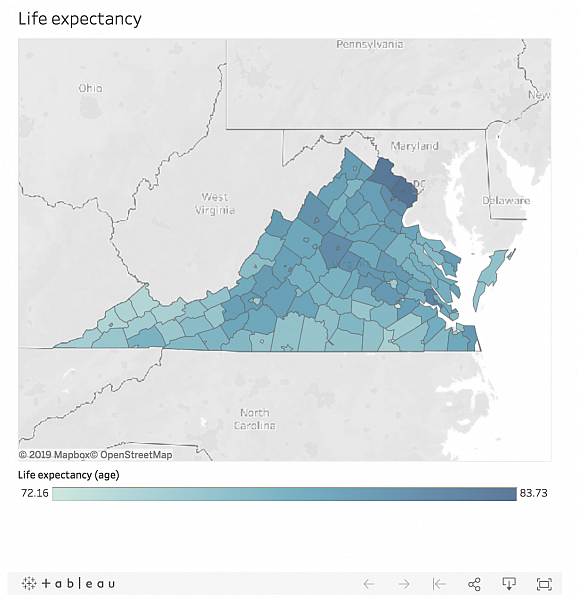

People living in the state’s Appalachian region live less healthy lives and die younger than elsewhere in Virginia and the nation, and those living in the seven most western counties, which are part of the Central Appalachia sub region, fare worst of all.

The Appalachian Region includes all of West Virginia and parts of 12 other states, including the least populous western part of Virginia.

The Appalachian Regional Commission and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation in 2017 began reporting on health disparities. They are finding that people who live in the rural counties of the central region have higher incidences of heart disease, cancer and diabetes and die younger than those living in other parts of Appalachia.

Consider one measurement: years of potential life lost. The rate for the Appalachian Region is 25 percent higher than the national rate. Central Appalachia’s rate is 69 percent higher than the national figure.

Or look at deaths specifically from heart disease. In the United States in any given year, 175 people out of 100,000 die from heart disease. The rate of 160 people per 100,000 is lower in Virginia, and lower still at 155 people per 100,000 for non-Appalachian Virginia places such as Roanoke. In the state’s Appalachian counties, 217 people out of 100,000 people die from heart disease.

At the same time, Virginia’s coalfields have fewer doctors. In the Appalachian counties, one primary care doctor is available for every 1,900 people; in the rest of Virginia, the rate is one for every 1,400 people. The disparity is greater for specialists, with one for every 650 people in much of Virginia but only one for every 1,600 people in the the Appalachian counties.

An unusual merger

The stark differences in health are not new. In 2007, the General Assembly created the Southwest Virginia Health Authority as a way for area leaders to discuss and recommend ways to improve health and, thus, the economy. The group met every so often but lacked clout to make changes, Kilgore said.

It adopted a blueprint for health in 2009, and in its first progress report of 2011 it discussed some of efforts underway in the region but noted that little to no progress had been made on many of the goals.

At the time, two rival hospital-based systems delivered much of the health care in far southwest Virginia and northeastern Tennessee. Both Wellmont Health Systems and Mountain States Health Alliance wrote off a high volume of uncompensated care for patients who lacked insurance or could not pay their deductibles. The population was aging and declining, which placed further financial burdens on the systems.

Then in 2013, without warning, Wellmont closed its hospital in Lee County, putting 140 health care workers out of work, 25,000 people out of reach of fast emergency care and the county out of contention for growing its economy.

The rivals began to talk about merging, a scheme likened then to being as if Virginia Tech and the University of Virginia fielded a joint football team.

Ordinarily, the Federal Trade Commission rules on whether the benefits outweigh the losses that come from a lack of competition, but Kilgore crafted a regulatory process so the state could have control.

Kilgore said in a recent interview that he knew the merger and the loss of competition would be better for his constituents than if either or both of the rivals partnered with a system from outside the region.

“If an outside force came in, then we would have no say in the process. They would just close, downsize or do whatever they needed to do to make sure their hospital group was financially able. This was, by far, better for southwestern Virginia,” he said.

The FTC filed objections to the merger, as did insurers concerned that the lack of competition would drive up prices and physicians concerned that they’d be blocked from practicing.

“Competition is very good where it can be supported by the market. In a market where you have a declining population and declining inpatient-use rates and all this fixed capacity, you have to come up with a rational way to utilize that capacity or somebody is going to go out of business,” said Alan Levine, the head of Mountain States, who would become CEO of the new Ballad Health. “We said the entire time we advocated for the merger, that rather than see rural hospitals close, we think there’s a way to sustain these assets and jobs by being rational in the marketplace.”

The regulatory process would require Kilgore and the authority to look more deeply at how the competition prevented investments in community health, and to better understand the barriers to health care.

“What really surprised me was our lack of access, and that we didn’t have specialty care. We’re talking things like heart, cancer that you should have access,” Kilgore said. “Even primary care, you think you have enough until you look at basic statistics and you ferret it out and read some of these studies, and you go, oh my gosh, we really don’t have access.”

In January 2016, the authority developed a blueprint for health that establishes specific, measurable goals for improving lives and life expectancy. Virginia’s health commissioner incorporated those goals into the merger’s approval. Both states are requiring Ballad to spend $75 million in the next decade on improving population health.

Virginia has a short list, following the state’s health policy to use limited funds to do a few things well. Tennessee’s list is long and seeks to address historic neglect of population health measures by tackling all at once.

The requirements are unusual. Virginia usually has little authority to require hospitals to do much more than provide a percentage of charitable care in exchange for exclusivity to deliver certain services such as MRI or neonatal intensive care.

Kilgore said that Ballad is responsible for public health measures now and that he agreed to expand Medicaid in order to help Ballad meet that responsibility.

Medicaid expansion will bring Ballad both more patients with insurance and a higher reimbursement rate than under the previous program and eventually will help with physician recruitment, opening up better access to primary care and specialists.

But, Kilgore said, people still have a reluctance to see doctors.

“We don’t catch people until they are really sick,” he said. “There are a lot of prideful folks who are self-reliant, but once they see they can get some health care and get checked out, they’ll see that the sooner you can detect cancer, the better your chances are than if you wait until you get really sick.”

Tony Keck, Ballad’s chief population officer, said Medicaid expansion will mean fewer people will rely on charitable care like that of the RAM clinics.

“Health care is not going to look like it does today where you have these free independent clinics patching things together with duct tape and everything else in trying to deliver services,” Keck said.

Data editor Kate Owens contributed to this report.

[This story was originally published by The Roanoke Times.]